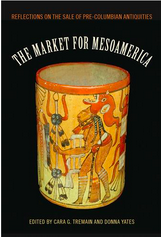

Cara G. Tremain and Donna Yates, eds, 2019, The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the sale of Pre-Columbian antiquities, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, xvi + 213 pp., ISBN 9780813056449

Keywords: antiquities, trafficking, Mesoamerica, market, law.

Cara Tremain and Donna Yates’s edited volume brings antiquities trafficking in Mesoamerica back to the scholarly limelight. This almost forgotten phenomenon, originally brought to the attention of scholars by Coggins (1969), and more exhaustively reviewed at the 1990 Dumbarton Oaks symposium (Boone 1993), has gone virtually unnoticed in academia despite the loss of cultural heritage in Mexico and Central America it has caused, and persists today. The selection of papers presented here explore the legal, sociological, archaeological, and museological aspects of the antiquities market in Mesoamerican artifacts. The theoretical foundations of the book rest on Actor-Network Theory and the Theory of Entanglement, which are broadly described in the introductory chapter by Rosemary Joyce. Joyce defines the market in Mesoamerican antiquities as “art world(s),” or a complex network of mutually-dependent, and thus equally responsible, actors that once created and now perpetuate the traffic in antiquities. The main actors participating in the Mesoamerican art market include looters, local authorities, middlemen, dealers, collectors, museums, as well as scholars. The actants, although implicitly identified as such, comprise the evolving taste in the arts, the choices of scholarly research, and the museum’s interest in exhibiting the Mayan material culture. These actants are responsible for building the commercial and non-commercial value in Mesoamerican antiquities.

Cristina Luke’s chapter excels in bringing the “artworld” network to light. She offers a historical overview of the connection between elite privilege, archaeological practice in the early twentieth century, and the socially accepted looting performed by American archaeologists in Honduras. The author reveals how American archaeologists used Cuyamel Fruit and United Fruit corporative infrastructure, as well as top-executives and diplomats’ political power and social influence, to fill up the most renowned U.S. museums. Thus, Luke demonstrates and expands on Joyce’s perception that archaeology plays a fundamental role in the antiquities market, not only as scholars have assisted in increasing the perceived value of Mesoamerican artifacts, but as they have actively participated in the trade of antiquities (often masquerading behind the “rescue argument” and the “broadening accessibility” façade).

Sofia Paredes Maury, Guido Krempel, and James Doyle look at the history of looting in, and looted objects from, Guatemala by focusing on a “source-country” perspective. Paredes Maury and Krempel’s chapter studies the extent of antiquities looting in the country by examining the chronological and spatial incidence of looting, the legal and managerial strategies to halt heritage trafficking in the country, and the significance of recovering artifacts that are privately held, both in Guatemala and abroad. Paradoxically, Doyle expresses in his chapter the difficulties of repatriating archaeological masterpieces to Guatemala due to the lack of resources and support, financial and otherwise. He chronicles the “odyssey” of Piedras Negras’ Stela 5, which had been exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art via Rockefeller’s collection, to exemplify the challenges archaeologists, but also collectors, encounter when attempting to reunite dismembered pieces and disassembled caches, or to return illicitly exported artifacts.

Doyle’s chapter serves to bridge the gap between the on-the-field looting and the journey looted artifacts embark on once they enter the “market-countries” network, the theme connecting Berger’s, Sellen’s, and Tremain’s chapters. Martin Berger reconstructs the object-biography of a group of Post-Classic turquoise mosaic artifacts, today scattered worldwide but purportedly originating from two close sites in Mexico. By studying their available provenance and post-depositional life, the author advocates for the scientific analysis of artifacts that lack a secure provenience in order to avoid a “double-loss” -the privation of the artifact’s contextual data and the information it holds in itself. Although this is a widely unpopular approach in academia, various authors in this volume support this practice (Joyce, p.13; Paredes Maury and Guido Krempel, p.78; Tremain, p.184), making it one of the compelling arguments throughout the book.

Adam Sellen also reacts to the dispersion of looted antiquities around the globe. In his endeavor to build an online catalog of Zapotec urns, the author narrates the multiple obstacles to access the archaeological material that has been disseminated through trade, and the moral dilemma of having his prolific database misused. Despite the goal of creating the Zapotec catalog to facilitate scientific research, dealers and forgers have found in it a reliable source of information to give looted objects academic legitimacy. The problems of legitimacy, provenance, and provenience in the antiquities marketed by the most eminent auction houses are the core subject in Cara Tremain’s chapter. She tracks the distribution of Mayan antiquities at Sotheby’s over a period of fifty-five years, by examining the existent auction catalogs and sales databases. She proves that the inherent opacity and well-guarded anonymity in the antiquities market allow the ongoing penetration of illegal artifacts, as well as forgeries, for sale. On that note, Nancy Kelker claims that the presence of fakes in the art and antiquities market is ubiquitous. The production of forgeries dates as far back as appropriation of cultural artifacts: both phenomena originated in response to the high demand in the art and antiquities market. In this chapter, Kelker argues that developing and applying measures (forensic testing, expert evaluation) to identify forgeries before they get into the market is the only way to prevent them from contaminating scholarship.

Allison Davis and Donna Yates touch upon the law regulating the flow of Maya antiquities into the U.S in their chapters. Davis discusses the heritage-related bilateral agreements between the U.S. and all Mesoamerican countries, under the Property Implementation Act (CIPA). The value of these agreements not only rests in their primary objective, which is restricting the importation of stolen and looted materials into the U.S., thus reducing the incentive to loot in the first place; but the collaborative binational relationships concomitant to the ratification. The ongoing professional and diplomatic interaction fosters dynamics of cooperation and mutual support, along with the establishment of concrete measures to protect the cultural heritage. However, Yates argues that the enforced heritage policies do not produce the expected effects in preventing looting and trafficking because of their country-specific approach. Since the ancient Maya area does not correspond to the current political division of Mexico and Central America, the difficulties in ascribing the country of origin of the artifacts being traded hinders the enactment of country-to-country bilateral agreements. Instead, heritage laws require an object-specific model, similar to the policies restricting the traffic in endangered species. Hence, banning U.S. importation of all undocumented Mesoamerican artifacts may be a more effective avenue to halter illicit trade, and consequently, reduce archaeological looting.

In conclusion, this book is designed to stir scholarly interest in the illicit trade of Mayan artifacts. While presenting a well-documented, historical overview of the looting practice in Mesoamerica, the book’s fresh insights break new paths of research in archaeological looting, the antiquities trade, and national and international heritage law. Addressing the antiquities market as a self-contained artworld might give scholars the key to fully understand its mechanisms, and to confront it successfully once and for all.

Works Cited:

Boone, E.H., ed. (1993). Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library Collection.

Coggins, C.C. (1969). Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities. Art Journal 29 (1): 94, 96, 98, 114.

Irene Martí Gil is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Geography and Anthropology at Louisiana State University. Her field of research is focused on the archaeological looting and the antiquities market from an interdisciplinary (legal, archaeological, ethnographic, and linguistic) perspective. At present, she studies the cultural heritage laws enforced in Guatemala and Belize, with the objective of expanding the research scope throughout the Maya area in the near future.

© 2021 Irene Martí Gil