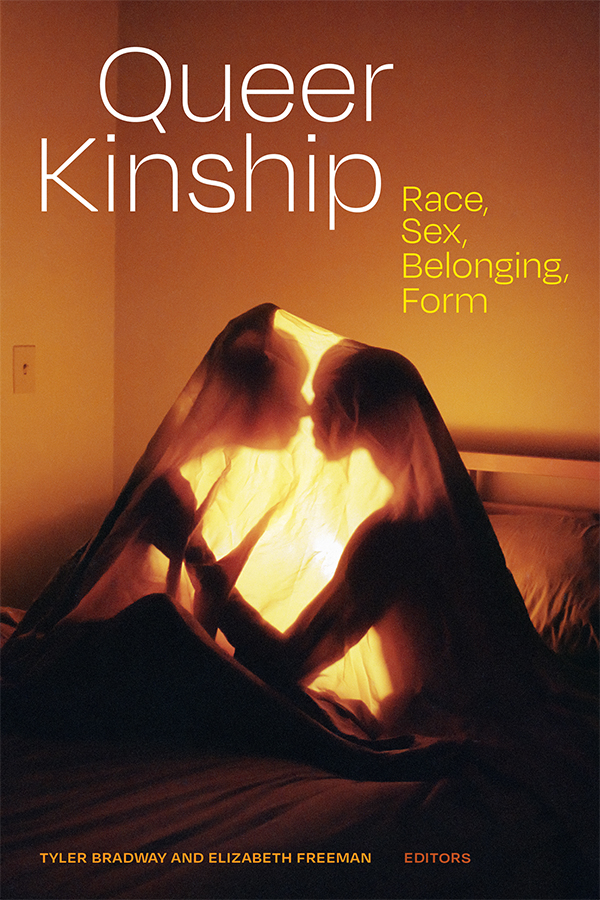

Eds. by Tyler Bradway and Elizabeth Freeman, 2022, Queer Kinship: Race, Sex, Belonging, Form, Durham: Duke University Press Books (Theory Q), 360 pp. ISBN: 9781478016021

Keywords: Queer Kinship, Queer Theory, Kinship Theory, Black Kinship, Indigenous Kinship, Trans Kinship, Kin

In this volume edited by Tyler Bradway and Elizabeth Freeman, the authors build on and challenge kinship as it has been researched and theorized while arguing for the relevance of kinship research to queer, trans and critical race theories today. The various topics through which kinship is explored in this book also importantly encourage new routes for theorizing kinship, both as a concept and lived/sensed experience. The volume considers kinship’s linkages to issues that all too often have been obscured or overlooked by kinship researchers – issues such as colonialism, slavery and racialization as well as the linkages to nationalism. Intersections of queer, Black and Indigenous lives and experiences are thus central to this volume, lives and experiences which have been invisible yet foundational for how kinship has been shaped and understood by dominant (white, colonial) narratives. The forms that the narratives in this volume take and analyse move between ethnography, fiction, history, imagination, memories, stories, and storytelling. While taking various routes, they unite through desire as a moment of departure from where kinship is explored. As Bradway and Freeman stress, kinship has always been connected to desire, and not always a desire to connect – at times a desire to disconnect (3). It is thus also about movements, how (Black, Indigenous, queer, trans) kinship moves between but also beyond time, space, place, bodies, selves, memories, violence, hopes and imaginations but also beyond kinship itself.

The volume consists of 12 main chapters organised under three sections. The editors emphasize a fluidity to the chapters as they could easily be positioned within other sections. The fluidity also refers to the previously mentioned importance of form for this volume, form as both something kinship is analysed as and through. The whole book works to answer questions on why kinship still matters and why now, questions which the introduction considers when laying the foundation for the upcoming chapters. In the introduction, we are presented with three key concepts – “kincoherence,” “kin-aesthetics” and “kinematics.” The essays give a “conceptual frame” to address “the kincoherence, kin-aesthetics and/or kinematics of queer kinship” (18). (Kin)coherence/(k)incoherence helps to understand the “temporal dimension of kinship” – how kinship remains a “horizon of violence and possibility.” It works to trouble what kinship binds and unbinds (3, 11). Kin aesthetics, in turn, is to understand processes of figuration and form; kinship as embodied and material, but always in transformation (4, 5). Lastly, kinematics addresses kinship as movements – not only beyond the normative but “within, across, and between” configurations of kinship (13). The volume closes with an epilogue in the form of an interview with Kath Weston, author of “Families we Choose,” a significant work within queer kinship research. Weston addresses queer kinship as embedded social practices, as transformations rather than structure or form. The interview spans between the then and there and the now and here of queer kinship to discussions on how queer kinship research opens up possibilities for academic routes that may not be obvious in their ties to kinship theory.

The essays of part one of the volume, Queering Linages, address temporalities of kinship beyond linear genealogy. In Judith Butler’s essay, the presumed distinction between natural (blood) and fictive kinship ties is in question as Butler focuses on belongings beyond bloodlines. Specifically, the regulation of “race” through kinship and how this reproduces racialised violence through time. In Brigitte Fielder’s chapter that follows, which analyses queer genealogies of interracial kinship, “mixed-race self-begetting” is explored “as a queer act of self-reproduction.” The essay discusses the (queer) potential found in the aesthetic as well as the racial reproduction happening through the aesthetic (disputing a reduction of “race” to biological reproduction). In Dilara Çalışkan’s essay, temporality is approached through intergenerational memory across time and space among trans mothers and daughters in Istanbul. In these mother-daughter bonds, memory is a tool for survival (in various ways) and also that which much shape these kinship bonds. Part two of the volume, Kinship, State, Empire, works on the de/anticolonial, the beyond/outside of the colonial bondage – thus also contesting the Eurocentric research. Joseph M. Pierce opens the section by exploring indigenous kinship through the concept of “kinstillations.” It is a call to return to Indigenous ways of being “in good relations” – to the land, to spirits, and to ancestors across time. Pierce emphasises Indigenous kinship as something you do rather than have, as “a reaching” (98). Kinstillations is like “reaching for the stars,” a simultaneous reach for the future and travel to the past. From here we move to the topic of surrogacy in Poulomi Saha’s essay. Saha analyses postcolonial India’s attempt to ban commercial surrogacy, queer kinship’s ties to the politics of the global neoliberal market, and the ways that surrogacy is being transformed within this market. The individual agency within surrogacy, Saha argues, is transformed into a form of contract mediated by the form of family that deems feelings of generosity and gratitude as compensation for the surrogate. Mark Rifkin also addresses governmentality. In this chapter, Rifkin addresses how Indigenous social logics contest the equal sign between family and kinship uniformity. Indigenous forms of relationality, Rifkin argues, enable a move to queer non-neoliberal governance. In the following essay, Aqdas Aftab works with black trans-fiction to decolonise trans-interiority and find the “elsewheres” that support Black trans lives. Aftab takes the gaze from the fetishized (Black, trans) body to the interior and the “ecstatic kinship” found within. Here memory and imagination hold “utopic and ecstatic work” rather than the future (169). Juliana Demartini Brito analyses kinship performances among activists taking part in the mass protests that followed the murder of Black, lesbian politician Marielle Franco in Brazil. The phrase used by activists, “Marielle Presente,” both speaks of the presence and absence of Marielle – linking activists through time, grief, and desire as well as tradition and change. Moving on to part three, Kinship in the Negative, a section that rethinks queer belonging and unbelonging by building on and expanding traditions of queer negativity and anti-social thesis. Christopher Chamberlin’s essay “Akinship” (“a-kinship”, “akin-ship”) emphasises racial production as the very structural cause of kinship. Heteronormativity takes part but kinship is “always the absolute repudiation of Black kinship.” “Akinship” speaks of the social impossibility of Black kinship. The “negative” in the essay by Leah Claire Allen and John S. Garrison is towards the link between queer kinship and the “chosen family”. The authors do not contest lived experiences but how narratives of queer friendship have been absorbed by neoliberal ideals. Natasha Hurley, in turn, contests dominant narratives on childlessness. “Kidless lit” speaks of other narratives and meanings found within our relating to “other people’s children.” Kinship is here analysed through cross-generational relationships that make “kin not population” (referencing “Making Kin Not Population” from 2018, edited by Adele E. Clarke and Donna Haraway), thus moving beyond family/reproduction norms (251-253). The last essay by Aobo Dong returns to blood as kinship, shaped through martyrdom, oath, sacrifice, and violence among Chinese blood brotherhoods. Blood here produces kinship bonds through death (as survival and resistance) rather than birth.

This book moves the reader, not only along the routes the authors take but beyond these. Even when walking along paths paved by many, we always walk with a different view as the “landscapes” we move through and within continue to change. For me, the major take from this volume is not necessarily the arguments (important and thought-provoking as they are, with their strengths as well as limitations). Rather it is how it inspires the reader to not only think of kinship as a concept and what this concept does, but to think of kinship in terms of narratives and heritage – whether dominating, contested and/or possible. In times when the future may feel more uncertain and precarious than ever, it also reminds us of the potential there is in memories and imagination – that which is already here. Kinship, to draw from Çalışkan when analysing the notion of “home,” can help to find our archives “of feelings and emotional and temporal investments” (78). The book is primarily an important creative and analytic contribution to contemporary queer, trans, critical race and kinship theory. Nevertheless, it is also of value for those who explore narratives and form as well as belonging and heritage “beyond” kinship relations. As Weston illuminates, when exploring kinship, it can, if we are open to it, take us on unexpected routes.

Rebecka Rehnström is a PhD student at the University of St Andrews. Her research interests lie within feminist and queer anthropology with a specific focus on material and visual culture, LGBTQ+, activism and performance. Her current research is on queer urban future and heritage narratives among LBTQ+ women and genderqueer people in Scotland.

© 2022 Rebecka Rehnström

![]()

Rebecka Rehnström is a PhD student at the University of St Andrews. Her research interests lie within feminist and queer anthropology with a specific focus on material and visual culture, LGBTQ+, activism and performance. Her current research is on queer urban future and heritage narratives among LBTQ+ women and genderqueer people in Scotland.