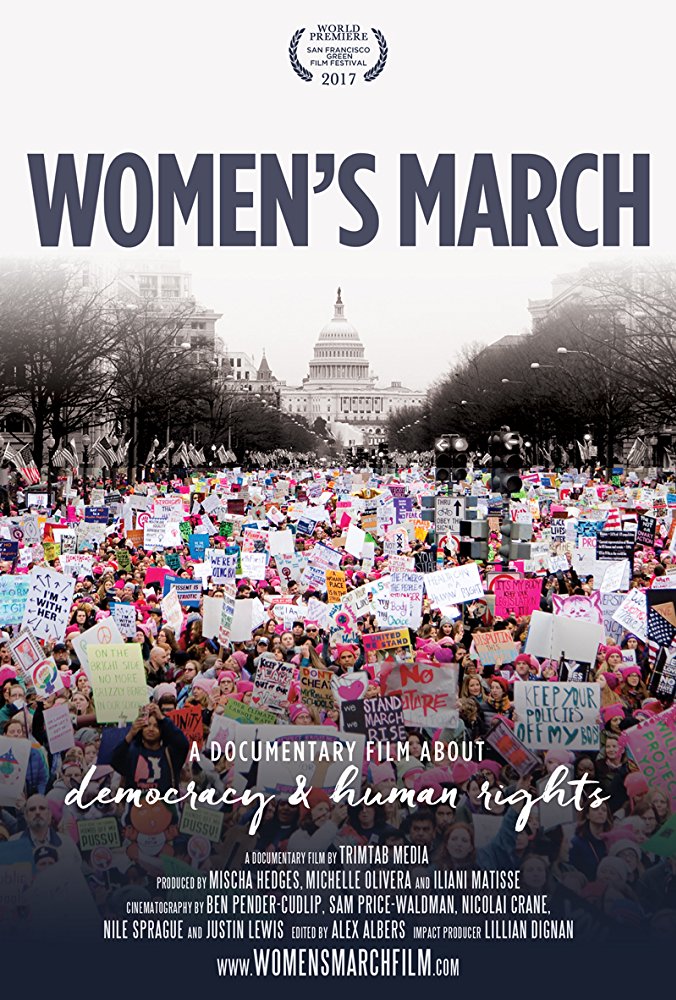

Mischa Hedges (director), 2017, Women’s March: A Documentary Film About Democracy and Human Rights, TrimTab Media

Women’s March: A Documentary Film About Democracy and Human Rights was produced in 2017 by TrimTab Media, an agency whose aim is to produce independent documentaries which highlight social and environmental issues. Mischa Hedges, co-founder of the agency, directed and produced the documentary with Michelle Olivera and Iliani Matisse. The project began when the team contacted the San Francisco Bay Area Women’s March organizers to tell the story of the Women’s March and to create a space of critical thinking and exchange about democracy and human rights. It also aims to provide tools and strategies to inspire listeners to assert their rights when they are compromised. In short, the team’s main goal was to make this documentary accessible to the academic community, and to amplify the voices of people attending the Women’s March across the United States. On January 21, 2017, the main march was held in Washington, DC, where nearly 725 000 people attended, but several “Sister Marches” took place elsewhere in the United States and around the world.

This short 30-minute independent documentary is shot with five difference women in five American cities – Boston, San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Rosa, and Washington, DC – the day after the inauguration of the new President, Donald Trump. These five women share their background and motivations to participate in the march. First is Angela Washington, a black woman who attended the walk in San Francisco with her daughter Maya. The latter shares a particularly revealing testimony of the reality of black people in everyday life, mentioning that she is afraid every day for the safety of her brother, who is a male nurse, because some people are afraid simply because of the color of his skin. There is also Bellx April1, a Xicana from Mexico and Los Angeles who walked in Boston; Gretchen Goldman, a scientist who participated in the march in Washington (DC); an Afghani refugee Lila Samady, who attended the walk in Oakland (CA), and Marylou Shira Hadditt, an 88-year-old Jewish woman who walked in Santa Rosa. These women have multiple reasons to walk, and they talk about the desire to fight for their rights, to signal their disagreement with President Trump’s political intentions as well as austerity, gender inequalities, racism and climate change. For example, Lila wants, among other things, to pay tribute to her parents who experienced a lot of difficulties and who, despite their important status in Afghanistan, decided to leave everything behind to ensure the safety of their children. She also wants to oppose Trump’s proposed immigration policies and deportation. As for the others, Angela speaks about passing the torch to her daughter, and empowering her. Bellx is particularly inclusive, mentioning the importance of social movements like Black Lives Matter, the Queer and Trans community, and Indigenous people. Bello also highlights the persistent racial segregation towards First Nations by informing us that there were two marches for women in Boston: one for women “in general” and one for the indigenous women, since the latter were not welcome in the organization of the Women’s march. This last point shows that there were relevant irregularities in the planning of the event.

The documentary also features speeches by Senator Elizabeth Warren, Senator Kamala Harris, Gloria Steinem, a Feminist Writer, Lecturer and Political Activist, and Malkia Cyril, the executive Director of the Center for Media Justice. Some activist’s speeches, such as Malkia Cyril’s, were very hard-hitting and inspiring, particularly when quoting Audre Lorde: “When I dare to be powerful to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid. Together we can transform fear into power.” She mentions the Black Lives Matter movement and an important reminder that this was not a parade, also stressing the importance of keeping up the protesting and resisting actions. At this point, it could have been interesting for the documentary to feature the speeches that Raquel Willis or Janet Mock made during the event speaking for trans people, particularly when taking into account that black transgender people are widely persecuted and at risk for sexual violence and transphobia.

Although the five women’s speeches are interesting and relevant in the context of the documentary, it should be said that these women come from an intellectual background. Although they have lived – and continue to experience – injustice, they have an history of militant involvement (for the most part), they already have a thoughtful position and an well-constructed argument on the topic, and they mostly are in the middle and upper classes. Shira Hadditt, for example, has led a decades-long fight for civil rights. In contrast, no voice is given to the most “invisible” people, the “marginalized” ones, the most “excluded” of the excluded. Bello and Angela mentioned the rights of LGBTQ people and the documentary also shot some posters about those rights, but nothing more. Nobody talked about the rights of sex workers either, even though sex workers are also particularly at risk of sexual and gender-based violence.

If the purpose of the film is to stimulate reflection and discussion, and to motivate social engagement, it is essential to have a critical look at the event itself. Indeed, the event had been particularly questioned and criticized, especially in regard to the fact that it was conceptualised by white people, and that black women, indigenous, trans, and sex workers were very underrepresented, if not forgotten. We can clearly notice in the documentary that there were mostly white protesters among the crowd. In addition, the goals of the march are so wide and numerous that they become diffuse: what are the reflexive and critical aspects of the March? Did it serve the women’s cause? Was it representative of the values that it advocated? What were the opinions about this March? Was there a goal, a general guideline behind the tenure of the March?

Otherwise, the documentary is aesthetically well done, and it is obvious that the efforts invested both to finance the project and to realize it are important. It presents the points of view not only of the five key participants presented above, but also of some speakers, as well as several people from the crowd, such as the words of some men, and a woman representing an organization for the respect and inclusion of Muslim people. The documentary illustrates the global reaches of this march, the solidarity that has been woven among people, and the magnitude that the event has taken. It has the merit of presenting a very inspiring solidarity movement throughout the world, presenting not only images of the marches of the five cities in question, but also of some of the Sister Marches. The documentary demonstrates that rights should never be taken for granted.

Finally, at the end of the documentary, listeners are invited to visit the Women’s March documentary website to download the “take action guide” to stay engaged. In this guide, points are to engage in politics locally and nationally, to use our power of consumption intelligently and according to its own values, to attend events, gatherings and actions, to get involved in volunteering and to stay informed. Under each of those points electronic resources are available. This aspect is an honorable way to give people a view to long-term commitment.

Without a doubt, Women’s March: A Documentary Film is a relevant one. It is helpful to induce thoughts and actions, and it will surely offer the opportunity to debate the subject of human rights and democracy. However, it represents an introduction: an upstream and partial representation of the event.

Notes

- Considering that indigenous people have suffered from ostracization, including by misleading appeals, it was not clear to me how Bello April, one of the participants of the March, wanted to be identified. I contacted her and explained that I was writing a review about the Women’s March documentary in which she participated. After our talk, she thanked me for having contacted her and for the intention. She told me then that she would like to be identified as Bellx, a Mexican xicana from Mexico and Los Angeles, after the queer orthographic rule – to replace the word’s ending by an “x” to symbolize of gender neutrality.

Educational Licenses for this film can be purchased through THE VIDEO PROJECT

Véronique Senécal-Lirette is completing a Master in Social Work at the Université du Québec en Outaouais. Her master’s thesis is about the experience of unveiling domestic violence from women in Kaolack (Senegal). She had worked in domestic violence shelters and as a volunteer at the Montreal Sexual Assault Centre.