WILLIAM S. SAX, 2024, In the Valley of the Kauravas: A Divine Kingdom in the Western Himalaya, Oxford University Press, 320 pp., ISBN 978-0-19887-935-0

Keywords: Divine Kingship, Public Enactment, Cultural Solidarity, Local Deities, Ballad and Oral Tradition

The Valley of the Kauravas by William Sax is a beautiful yet candid work, showcasing his approach to data gathering (p. 17) by weaving his personal experiences into the narrative using “reflexive” ethnography. This method allows the book to convey deep emotions and messages, rather than simply recounting a series of stories. Sax opens the book with a dedication to Buli Das, the ‘Dhaki,’ whom he regards as both a teacher and guide, as well as a dear friend during his research in the Rawain Valley—a place where he spent over three decades working. The epigraph is particularly captivating, as Sax offers salutations to Karna, the son of the Sun God, in the local dialect, thereby connecting his presence to the local deities—Hari of Haridwar, Lord Badrinath, and Kedarnath—and the sacred Ganges River. The book is a seamless blend of both transliteration and translation, comprising nine chapters, including the Introduction. One of the book’s most striking features is the interconnection between the chapters, each linking to the next in some way, creating a cohesive and engaging narrative.

Chapter 1 introduces the local gods, portrayed as divine kings ruling over kingdoms in the Rawain region of Uttarakhand. These gods control weather and periodic trends, a concept Sax explores for modern readers who might find divine kingship puzzling. He examines this through an anthropological lens, discussing the intertwined nature of religion and politics in classical South Asian politics, with Raja Karan, a key figure from the Mahabharata, central to the narrative. The chapter is divided into three parts. “Gods as Agents” highlights how deities like Raja Karan require oracles and drums to exercise their agency, with Sax using an example of an American voter to explain this concept. He notes that local deities have distinct personalities, like Karan’s gentleness compared to Duryodhan’s anger. Sax also discusses Kinnaur, where ruling deities are generally queens, and provides a narrative about the Mahasu brothers and animal sacrifice. The second part addresses three problematic terms: culture, ontology, and rituals. Sax views culture as a space for disagreement, not just shared beliefs, and agrees with using ontology to investigate the nature of being. He introduces the concepts of “real-izing” and “worlding” instead of “culture” and “ontology.” The third part sparsely uses the term “ritual,” as Sax prefers “public enactment,” arguing that rituals shape the context rather than being shaped by it.

The core of Sax’s book centers on how humans have created and continue to recreate a world where they interact with their divine kings. Chapter 2 delves into divine kingship in South and Southeast Asia. Sax begins by discussing Dumont’s argument that, although the Brahman is spiritually superior, he is materially dependent on the king, highlighting the “conundrum of the king’s authority.” Sax emphasizes the inseparable nature of religion and politics in classical South Asian politics, where the king is seen as divine. In Rawain, Raja Karan embodies both a world-renouncing yogi and a decisive warrior-king. Dirks (1989), who views religion and politics as two sides of the same coin, and Sax cites examples from the modern king of Puri to illustrate this. Sax later discusses the integration of kingship and religion in Garhwal, referencing Galey’s argument that they are two parts of a whole, leading to three patterns:

(a) Legal rule by gods embodied as temple images (e.g., Kullu and Mandi).

(b) Kings and gods as reflections or alter-egos of each other.

(c) Divine kingship—direct rule by gods (e.g., Rawain).

Sax includes a map detailing Kangra, Mandi, Sirmaur, and Tehri-Garhwal (p. 48, Fig 2.1) and mentions God Mahasu’s role in providing justice and resolving conflicts, effectively setting the stage for the book’s further exploration of divine kingship and its impact on the region’s people.

From Chapter 3 onward, Sax shares captivating stories that enrich the narrative. The first takes place on a winter afternoon in 1994, where Sax joins Rajmahon (the Vazir of Karan), Ram Prasad Nautiyal (God’s Brahmin oracle), and Raja Karan, who, through his oracle, predicts the future and resolves disputes. Sax explores different facets of Raja Karan’s identity: as a Brahman, a Yogi, a King, his role in the Mahabharata, and his conflict with Chalda Mahasu. In the Mahabharata, Krishna praises Karan’s generosity. As a king, Karan ruled Devra, with Sax highlighting the central-periphery dynamics of kingship. A key event is Karan’s confrontation with Mahasu, where Mahasu accuses Karan of black magic. Despite this, Karan is depicted as a vegetarian who upholds Hindu practices like Kanyadaan, guiding his people toward Brahmanical values while blending his divine role with traditional Hindu practices.

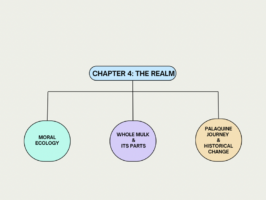

Chapter 4, one of the longest in the book (Fig. A), begins by introducing Rawain as a “mulk” (country), but it extends beyond this definition to encompass a bimoral system involving people, animals, gods, lands, and spirits. Sax explores this through the concept of Moral Ecology, where Karan communicates with his subjects via oracles, illustrated with photographs that provide a photo essay-like glimpse into the region. The chapter connects various elements of the mulk to the construction of a new temple rooftop. It describes a ball game played between two village groups, Panshi and Shathi, during Uttarayan and Dakshinayan. Another key element is the Palanquin journey, culminating with Raja Karan’s desire to travel to Khansyani village. The chapter also includes a headhunting incident and portrays village rivalries, increasing reader engagement.

Fig. A: The division of chapter 4 in the book into Moral Ecology, Whole mulk and the Palaquine journey. Image by author.

In Chapter 5, Sax addresses folklorization as a projective term, focusing on three main issues: (i) defining the objective of studying folklore, (ii) the shift from unconscious to conscious practice, and (iii) the association of folklore with power. He discusses the ballad of Jariyan, narrated by Buli Das, and the traditional enemies involved. Sax uses local dialects alongside translations, allowing readers with good imagination skills to vividly picture the unfolding drama.

Chapter 6 explores the theme of existential threat and the implications when solidarity is questioned. The chapter begins with Rajmohan’s political rivalries, leading into a summary of Rajmohan’s autobiography. It then addresses “crime and punishment,” discussing concepts of good karma and fate, and introduces a new angle on murder. The chapter concludes with a focus on summer and autumn festivals, connecting back to the initial story of rainfall from earlier chapters.

In Chapter 7, Sax begins with the question of how people create their world, focusing on the concept of “doing.” He shares anthropological insights on pastoralism, discussing sustainability, perceptions, ecological perspectives, and environmental determinism, before delving into transhumant pastoralism as observed in Rawain. The chapter also addresses the bride price and concludes with another ballad. The use of vivid photographs, ballad translations, and maps enhances the chapter, which primarily deals with the theme of grazing tax.

Chapter 8 begins with a salutation to the divine king and explores the idea that gods are not omnipresent; their power relies on the devotion and solidarity of their subjects (as discussed in Chapter 4, p. 79, and Chapter 9, p. 252). The chapter presents two cases involving the Pokhhu Devta, the god of justice and injustice. Sax recounts a family quarrel he witnessed, illustrated by Fig 8.2, a kinship chart that clarifies the dispute. The second case involves the chief minister, highlighting how people’s faith and moral solidarity strengthen the god’s power.

Chapter 9, titled “The Enemy,” centers on Duryodhana, who is worshiped as Lord Someshvar in the region. Sax discusses recent advances through the lens of modernization theory and notes that, unlike in the Mahabharata, Karan and Duryodhana are rivals in Rawain. He describes two forms of belief in the village: traditional practices and reformist views. The chapter also includes a story about a shepherd known as “Redcloak” and the Jakhol village’s idol-related narrative. Reforms, such as the ending of animal sacrifice, are highlighted. Sax presents his personal viewpoints through a three-world system: the childlike world of innocence, the competitive world of khunds, and the world of devotional Hinduism.

Overall, I was impressed by the volume’s organization, especially the palanquin on the cover. The Index at the end, which clearly lists page numbers, greatly aids readers. This commendable work is not only well-structured but also inspiring for future researchers and will be remembered for years to come.

References

Dirks, Nicholas B. “The Original Caste: Power, History and Hierarchy in South Asia.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 23, no. 1 (1989): 59–77. doi:10.1177/006996689023001005.

Abhijeet Singh Dewari, a graduate from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Delhi, has diverse research interests, including human growth and development, kinanthropometry, Himalayan studies, Kathak dance, physiological anthropology, and healthy aging. Remarkably, at the age of 13, he authored the book “A Man is Equal to a Coin,” which was published in 2019. Recognized as one of the youngest authors in the research community, he recently contributed a notable research article on the spirituality and injuries of Kathak dancers to the journal, Human Biology and Public Health.

© 2024 Abhijeet Singh Dewari