TRIGGER, DAVID S., 2025, Shared Country, Different Stories: An Anthropologist’s Journey, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 248., ISBN 978-1-83695-148-3

KEY WORDS: Forensic and Expert Social Anthropology, FESA, Native Title; Land Rights, Cultural Heritage Protection, Legal Pluralism, Customary Law, Indigenous Australia, Aboriginal Australia

Shared Country, Different Stories traces the 50-year career of Professor David Trigger, a leading member of Australia’s fourth generation of forensic and expert social anthropologists (FESAs) (Rose 2024a; 2023; Trigger 2023; 2025a). The book spans both Trigger’s extensive practical work with urban, regional, and remote Aboriginal[1] Australian communities on customary land rights and cultural heritage preservation, and his concurrent academic engagements at the University of Queensland (UQ) and the University of Western Australia (UWA). Although the central chapters of the text deal almost exclusively with Trigger’s professional experiences, replete with sprawling and detailed accounts of dozens of people and relationships, the opening and concluding chapters provide an intimate personal context rooted in his progressive Jewish upbringing in suburban Brisbane.

The development of FESA practice in Australia can be divided into approximately five generations, commencing with the admission of social anthropological evidence to Australian courts and tribunals in the late 19th century (Rose 2022). Following the academic institutionalisation of social anthropology in the 1920s, and until the late 1960s, the first three generations of social anthropologists who specialized in Indigenous Australian cultures both practiced and trained in a form of what has historically been termed ‘applied’ anthropology, contributing to government regimes of coercive control over Indigenous communities (Rose 2024b; 2024c; 2022; Trigger 2011; 2013; Asche and Trigger 2011). This situation was completely reformed from the late 1960s, with simultaneous federal political recognition of Indigenous Australian peoples via amendments to the national constitution in 1967, and an unprecedented Supreme Court challenge to Commonwealth power over Indigenous peoples in 1968 (Rose 2024c; 2022). These events ushered in statutory customary land rights in 1976 and the broader emergence of legal pluralism in Australia (Rose 2024c; 2022). It was in the midst of this political and economic upheaval that Trigger graduated with an Honours degree in social anthropology from UQ in 1975, and was thrust into the dynamic and groundbreaking work of Australian FESA practice in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Trigger’s upbringing in a lower-middle class Jewish family, whose income came from his father’s work as a builder, meant that he was open to both cross-cultural encounters and rugged working conditions. His subsequent encounters with Queensland Aboriginal communities visiting at UQ, the glib activism and intellectualism of university life, and his own initial employment as a builder’s and surveyor’s labourer, primed him both for independently minded intercultural analysis and remote area fieldwork. At the same time, he was initially uncomfortable writing about Aboriginal cultures for solely academic purposes. For his Honours thesis he turned instead to auto-ethnography, interviewing Brisbane Jewish youth about their experiences straddling the boundaries of a cultural enclave. Unsurprisingly, when he presented a summary of his thesis to the local chapter of the Betar, boldly titled ‘Israel is only one form of Jewish expression,’ he found his pragmatic and independent thinking not uniformly welcome.

After initially taking a job teaching social anthropology to community development workers and schoolteachers in the Northern Territory capital of Darwin, Trigger was offered a more substantial role mapping cultural heritage sites in the Gulf of Carpentaria, in a region spanning the Queensland/Northern Territory border. While split administratively between Brisbane and the Canberra-based federal Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS),[2] the project’s operations were based at the remote Aboriginal community of Doomadgee, 2,000km northwest of Brisbane in the heart of the ‘Gulf Country.’ It was here that Trigger was fully embraced for the first time by a community into which he had not been born, but which would remain a central part of his personal and professional outlook.

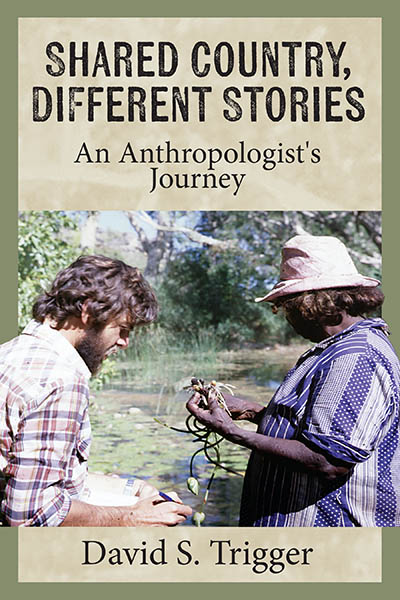

In the 1970s, Doomadgee was still controlled by a White Christian missionary bureaucracy that governed most aspects of residents’ lives. This form of coercive control had been the norm across Australia since the late-19th century, before being rapidly dismantled following the 1967 constitutional amendments, albeit at an uneven pace (Rose 2024c). For the people of Doomadgee, Trigger was a source of relief. With the AIATSIS-funded resources that he brought, including his professional and technical training, a four-wheel-drive vehicle, mapping, photographic, and audio recording equipment, senior community leaders were able to begin reversing the corrosion inflicted by mission management on their customary culture. Trigger spent the next several years driving thousands of kilometres with community members through the bush, recording cultural heritage sites, mythology, and the history of the Garawa, Waanyi, and Ganggalida people.

In return, Trigger was welcomed into the community as an adoptive younger brother of Garawa man, Johnny Watson, making him classificatory son of elder matriarch and community leader Emily Arthur, who genuinely ‘took him on’ as a family member. As a consequence, Trigger was conferred the Garawa sociocentric kin term or ‘skin name’ Bulanyi, transforming him into a ‘socially meaningful person’ (Trigger 2025b, 75). The agnosticism towards individual ethnicity that Trigger experienced at Doomadgee in the early 1980s is a fundamental and shared feature of traditional hunter-gatherer kinship cultures across Australia, the flexible inclusivity of which is a major factor in their endurance for more than 50,000 years (Rose 2017).

From this point forward, Shared Country, Different Stories tracks Trigger’s rapidly developing career as an expert in traditional customary Aboriginal land and resource tenure and cultural heritage. Soon after starting his site recording work in the Gulf Country, he was also commissioned to deliver FESA services to the recently established Aboriginal-run statutory NGO, the Northern Land Council (NLC).[3] As a FESA consultant to the NLC while based at UQ, Trigger went on to undertake forensic investigations and to provide expert evidence and advice first to the Nicholson River (Waanyi/Garawa) land claim (Kearney 1985), and then to the Garawa/Mugularrangu (Robinson River) land claim (Olney 1990). From then on, Trigger was contracted to deliver FESA services to a range of clients engaged in multiple statutory and litigated matters in various courts, including both civil and criminal proceedings involving Aboriginal claimants, respondents, plaintiffs and defendants.

Throughout this expanding professional experience, one persistent theoretical, methodological, and ethical contradiction seemed to repeatedly appear. On the one hand, Trigger’s sought-after expert knowledge was substantially the product of his membership of the Doomadgee community, and his ethical commitment to Aboriginal people’s customary rights more broadly. Yet, on the other hand, Trigger’s professional independence and objectivity as a FESA practitioner was also demanded by the legal-administrative processes through which those rights could be recognised. Trigger was repeatedly required to demonstrate to lawyers and judges that deference to the latter does not require disavowal of the former.

Through the 1980s to 2010s, Trigger notes that the demand for FESA services ballooned as Australia’s pluralistic legal system continued to expand and diversify. FESAs with formal training in the provision of cultural translation and explanation services came under increasing demand from lawyers, judges, and government officials (Morphy and Morphy 2023). This demand intensified especially after the 1993 passage of the federal Native Title Act. The new legislation greatly expanded available legal pathways for Indigenous Australians to pursue customary rights in land and natural resources, as well as their statutory power to negotiate with government and industry. However, the Native Title Act also elevated the burden of proof and requirement for attendant forensic investigations and expert evidence and advice under a regime maintained by the Federal Court of Australia (Trigger and Blowes 2001).

At the same time and counter-intuitively, Trigger observes, Australian universities began to abrogate their role in properly training social anthropologists to do this work. As part of a trend starting around the early 2000s, he suggests, university anthropology departments began leaning away from training in core subjects of customary kinship, religion, language, and economics, and towards a form of bureaucratic policing in which a didactic philosophy of ‘moral order’ became the primary focus. Students were no longer taught how to map sites, model kinship networks, or conduct consultations in respectful and ethical ways, but instead how to centre their own personal experiences and perspectives. This trend permeated Trigger’s experience at UWA, where he spent the late 1990s and early 2000s. As Head of the Anthropology Department, he undertook a major investigation into competing non-Aboriginal cultures of land and natural resource tenure, while also establishing and running a university-based FESA consultancy supporting Aboriginal communities with land claims and heritage protection work (Trigger 2020). After his departure from UWA and return to UQ in 2007, the UWA FESA consultancy expired.

Ultimately, Trigger concludes the book with what might be characterised as a sense of unease at the trajectory of social anthropology in Australia since the 1980s. On the one hand, the field has played and continues to play a critical role in enabling and supporting Indigenous Australians’ hard-fought struggles for political, economic, and legal equality and equitable access to justice under the law. On the other hand, the historical academic home of social anthropology in Australian universities has, for the past 20 years, increasingly disavowed the legitimacy and factual basis of the very expertise that makes the field useful to this ethical and pragmatic role.

This book will be illuminating and inspiring for emerging generations of FESA practitioners hopefully yet to come forward, especially those committed to achieving real and tangible legal justice for culturally marginalised individuals and communities.

References:

Asche, Wendy, and David Trigger. 2011. ‘Native Title Research in Australian Anthropology’. Anthropological Forum 21 (3): 219–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2011.617674.

Kearney, Justice. 1985. Nicholson River (Waanyi/Garawa) Land Claim Report by the Aboriginal. Report by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. Office of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner. https://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/1984/7.pdf.

Morphy, Frances, and Howard Morphy. 2023. ‘Witness Statements as Cross-Cultural (Mis)Communication? Evidence from Blue Mud Bay’. Anthropological Forum 33 (3): 176–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2023.2271673.

Olney, Justice. 1990. Garawa/Mugularrangu (Robinson River) Land Claim Report No. 33. Report by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. Office of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner. http://www6.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/1990/23.pdf.

Rose, James W. W. 2017. ‘Kinship, Cohesion, and Space-Time: A Network Analysis of the Indigenous Population of the Murray Darling Basin’. The University of Melbourne. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/191247.

Rose, James W. W. 2022. ‘“Proposition X”: Social Anthropology, Science, and the Law in Australia’. Paper presented at American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting, Seattle. Cultural Expertise and the Professionalisation of Anthropology, November 9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365358533_’Proposition_X’_Social_Anthropology_Science_and_the_Law_in_Australia.

Rose, James W. W. 2023. ‘Forensic and Expert Social Anthropological Practice: An Introduction’. Anthropological Forum 33 (3): 153–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2023.2278405.

Rose, James W. W. 2024a. ‘Forensic Social Anthropology: Overview’. In Expert Evidence: Law, Practice, Procedure and Advocacy, Seventh edition, edited by Ian R. Freckelton. Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia, Limited. https://anzlaw.thomsonreuters.com/Document/I87e89da7f4a911e9a70db2c902807575/View/FullText.html?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&VR=3.0&RS=cblt1.0.

Rose, James W. W. 2024b. ‘From Applied to Expert Social Anthropology: Emerging Concepts, Terms, and Definitions’. Australian National University Anthropology Seminar Series (Canberra), April 29. https://rsha.cass.anu.edu.au/events/applied-expert-social-anthropology-emerging-concepts-terms-and-definitions; https://content.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2024/6/Anthropology_Seminar_1_2024.pdf.

Rose, James W. W. 2024c. ‘The Role of Forensic and Expert Social Anthropology in Peacebuilding and Disaster Recovery’. Paper presented at 18th EASA Biennial Conference, European Association of Social Anthropologists, University of Barcelona. July 23. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384868998.

Trigger, David. 2011. ‘Anthropology Pure and Profane: The Politics of Applied Research in Aboriginal Australia’. Anthropological Forum 21 (3): 233–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2011.617675.

Trigger, David. 2013. ‘Anthropologists as Expert Witnesses Concerning Aboriginal Australia’. In Expert Evidence: Law, Practice, Procedure and Advocacy, edited by Ian R. Freckelton and Hugh Selby. Thomson Reuters (Scientific) Inc. & Affiliates. https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/forensic-social-anthropology.

Trigger, David. 2020. ‘Distinguished Lecture: Native Title—Implications for Australian Senses of Place and Belonging’. The Australian Journal of Anthropology 31 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/taja.12341.

Trigger, David, and Robert Blowes. 2001. ‘Anthropologists, Lawyers and Issues for Expert Witnesses: Native Title Claims in Australia’. Practicing Anthropology 23 (1): 15–20.

Trigger, David S. 2023. ‘Anthropology in Australian Indigenous Legal Cases: What I’ve Learned from the Law and What Lawyers Have Learned from Me’. Anthropological Forum 33 (3): 162–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2023.2278402.

Trigger, David S. 2025a. ‘Land Claim Legacies, Native Title, and the Rigours of Indigenous Politics’. The Australian Journal of Anthropology 1 (11): taja.70006. https://doi.org/10.1111/taja.70006.

Trigger, David S. 2025b. Shared Country, Different Stories: An Anthropologist’s Journey. Berghahn Books.

James W. W. Rose is Senior Fellow with the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health at the University of Melbourne, Director and Senior Consultant with the forensic and expert social anthropological consulting firm Relational Modelling & Analysis (www.relational.net.au), and teaches with the Royal Anthropological Institute in London. James is a FESA practitioner with over 20 years’ experience providing evidence to Australian courts, tribunals, NGOs, and other legally empowered organisations presiding over land and natural resource claims, statutory cultural heritage protection regimes, child custody disputes, and medical negligence matters involving Indigenous Australian individuals and communities where customary culture has been deemed relevant. James was raised partly in the remote Central Australian freehold lands of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) and is ethnically Western European. His most relevant recent peer reviewed work is Rose, James W. W., David Trigger, David Martin, et al. ‘Forensic Social Anthropology’. In Expert Evidence: Law, Practice, Procedure and Advocacy, Seventh edition, edited by Ian R. Freckelton. Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia, Limited, 2024.

© 2025 James Rose

[1] In Australia, the term ‘Aboriginal’ denotes individuals and communities occupying the mainland continent of Australia prior to British invasion in 1788, including their descendants. The term ‘Indigenous’ is used more broadly to include both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Isander peoples, the latter of whom are Indigenous to a region also administered by the Australian Commonwealth, but who bear a more distinctive social culture.

[2] www.aiatsis.gov.au

[3] www.nlc.org.au