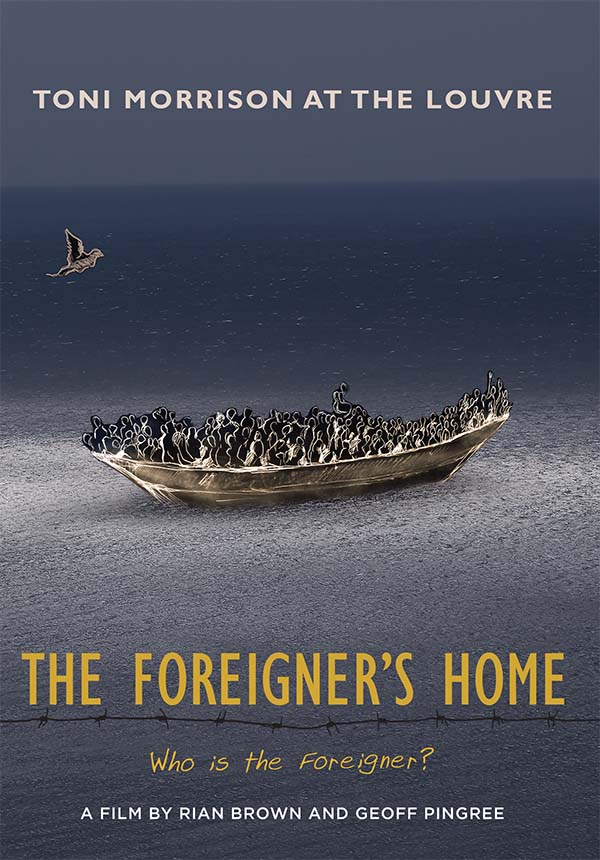

Directed by Rian Brown and Geoff Pingree, 2018. The Foreigner’s Home. The Video Project

The Foreigner’s Home is a compelling and poetic film that explores two central concepts in Toni Morrison’s work; the foreigner and the home. The film starts with footage from 2006 when Ms. Morrison was invited by the Louvre in Paris to curate an exhibition. With the same title, The Foreigner’s Home, Ms. Morrison decided to put the focus of the exhibition on the pain of exile and displacement. Engaging footage of the exhibition, intertwining with Ms. Morrison’s words, and animations, the film eloquently poses fundamental questions of our time: Who is the foreigner? How long does a foreigner remain a foreigner? Who decides what the foreignness is in a person? What, rather than where, is a home? What is the relationship between houselessness (lacking lodging) and homelessness (existential or politically imposed unbelonging)? Throughout the film Toni Morrison’s words and visions engage us into a conversation which is vital to understanding: ‘what does it mean to be human?’

A main protagonist in the film is ‘The Raft of the Medusa,’ the famous painting by Théodore Géricault from 1819. The painting depicts the tragic and grim aftermath of a shipwreck. A handful of survivors on an open raft struggle to survive. They are the ‘leftover,’ ‘undesirable,’ ‘surplus’ human beings; enslaved and poor laborers. For Ms. Morrison the painting shows a ‘raft cut off from the colonial ship,’ left-to-die.

Another main motif that reappears throughout the entire film is a short animation of a boat packed with people. The boat moves back and forward in the sea against the backdrop of a night sky. The juxtaposition of the early nineteenth century painting and current migrant boat disasters in the Mediterranean Sea exhibits the condition of coloniality along the European borders as an unfinished project. We hear her voice over the images of the animated boat packed with migrants moving closer to us:

“Foreigners are constructed as the sum total of the nation’s ills….We would be not merely remiss but irrelevant if we did not address the doom currently faced by millions of people reduced to animal, insect, or polluted status by nations with unmitigated, unrepentant power to decide who is a stranger and whether they live or die at or far from home.”

By a radical historicization Ms. Morrison shows that bordering and border practices are in a sense colonial practices. With references not only to the current European border policies but also by tracing the afterlife of slavery in modern American society the film unfolds a continuum of oppression and expulsion across place and time. To turn people into surplus people you have to first make them into foreigners. The question of foreignness is a question of race. In societies that are built upon the legacies of slavery and colonialism, being black (skin, hair, eyes) is unforgivable. As we see in the film, Hurricane Katrina swiftly turned racialized citizens into foreigners in their own homeland.

Another striking juxtaposition in the film is when Ms. Morrison invited slam poets, artists, and performers, who have been excluded from the ‘high culture world’, to the stage at the Louvre. Allowing their forceful words revealing racism, violence, and abandonment to echo in a museum crammed with a heritage made by white men. By bringing young artists to the stage, Ms. Morrison praises their ‘unpoliced language,’ a language regarded as corrupt, impure, and incorrect by the established white culture of elites.

The film then continues with video clips of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ showing drowning migrants in the Mediterranean Sea or migrants stuck at barbed wire borders along the Balkans in 2015. Rather than a crisis, it was, in the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot’s term, a disaster. Recurrent reference to ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ as an embodiment of fear, pain, and despair force the viewers to ask: ‘how can we respond to the disaster?’ Blanchot argued of the impossibility of the representation of the disaster. We cannot fully comprehend, and therefore we are not able to represent a disaster since we are not able to see the whole catastrophe, the full scale of what has happened.

The film directors failed to avoid the temptation of showing actual dramatic footages of migrants arriving by boats and getting rescued. Like in many other documentaries we see clips showing large number of black people squeezed on boats. The camera angle is always from the rescuers’ position recording the peculiar moment of arrival. The moment of rescuing black bodies from the wreck of the boats by white people in high technological vessels and equipment, including filmmakers’ cameras. Crying mothers. Traumatized children. Devastation. This kind of visual representation offers a constant presence of boats packed with de-named and defaced racialized bodies: a mass, a package of bodies, who represent ‘the crises’ and at the same time are filled with a constant absence of the very reasons behind the ‘crisis.’ Such images and clips fail to represent the disaster since the core horror of the disaster is always absent.

When in early November 2019 Europe was preparing the huge celebration of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Ms. Morrison had been passed away for a few months. I am sure she would not have taken part in the celebration. In 1989 there were 16 border barriers worldwide. Today there are almost 80. What is it exactly that we celebrate? As she eloquently reminds us:

“It may be that the most defining characteristic of our times….is that…walls and weapons feature as prominently now as they once did, in Medieval times.”

Despite all defeats and deaths due to the necropolitics at work along the walls, back in history and still, Toni Morrison’s vision leaves the viewer with hope.

Among the survivors in the ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ the viewer’s eyes are drawn to a male black body who is the composition’s figurehead. Seen from the back he is waving a tattered garment toward the horizon. He embodies hope. The film ends with a short passage from her Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1993:

“I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.”

It is in our hands and there is still possibility for a radical change to remake the world so we all will be foreigners and no one will be at home. Homelessness as a paradigm, as a horizon that the black man in the painting is gazing upon, as a way of being-in-the-world, as ethical and aesthetic normativity, opens the door to accept the foreigner as she is, not as how we want her to be. If we cannot escape the disaster, so paraphrasing Maurice Blanchot, let’s learn to think with disaster.

© 2019 Shahram Khosravi