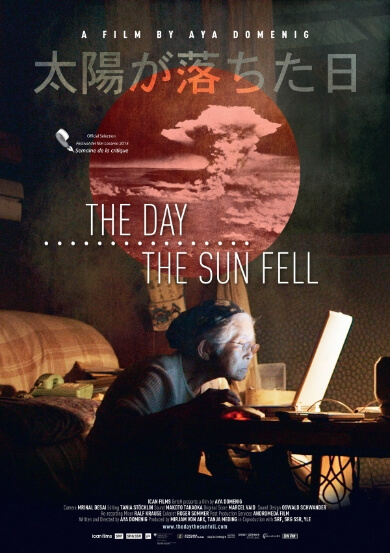

Aya Domenig, The Day the Sun Fell, ICAN films, 2015

On the morning of August 6, 1945, internist Shigeru Doi (1914-1991) left his family home in the countryside for his daily seventy-kilometer commute to the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima. He did not return until ten days later, and he greeted his wife on his return as if it were any other day. In the early moments of this ethnographic film, Kiyomi Doi (1926-2013) recounts the apparent ordinariness of that day. She remarked as unusual only that her husband silently went to the garden to eat fresh tomatoes, adding softly that that had left a strong impression on her. It had otherwise seemed like one more wartime day of bombing, a day a returning neighbour had mundanely described as having a big bomb fall. In Kiyomi Doi’s lifetime, she had known only war. Shigeru Doi never spoke of those days or of the ones that followed, nor did he write of them in his volumes of personal poetry. His granddaughter, visual anthropologist Aya Domenig, frames her account:

Only once did I ask my grandfather what he experienced in Hiroshima after the bombing. He answered that it was impossible to put into words. Those who had not been there would never understand. I remember that he was laughing and crying at the same time.

The Day the Sun Fell is a probing metanarrative that weaves a path through the public history of Hiroshima Day and the remembered stories of the ethnographer’s family and of hibakusha connected with them to ask: given this, then what?

The history is assumed known and appears as a series of film excerpts, most of only seconds in length, that are shown as a subject of discussion with survivors and family, both as remembrances and as part of the texture and activity of their lives during the following decades. This is neither history nor memory as much as it is a window on and a discourse about living intentionally amid the immediacy and the ongoing destruction of the atomic bombing. It is an ethnography situated broadly in the engaged and creative work recently setting the pace in anthropology (Wulff 2016, Fassin 2017). More specifically, it is an ethnographic film that understands and assumes a larger or more abstract political and discursive space and explores it through personal encounters in resonance with innovative intimate ethnography in war and its aftermath (Waterston 2014).

Domenig’s grandfather’s silence is arguably more of a rhetorical device than a literal depiction. Among the opening film clips Domenig selected is a very early scene of her grandfather identifying some of the atomic bomb damage done to a doorway. Her grandfather returned only four years after the bomb to live and practice medicine in Hiroshima and spent the last twenty years of his life with a debilitating illness that was quite likely a delayed consequence of radiation exposure. A fellow physician, Shuntaro Hida (1917-2017), who also lived through the bombing, comments on the choices people made to protect their children and grandchildren from the stigma of being Hiroshima survivors, potentially suffering and transmitting the long-term effects of radiation.

Domenig’s grandmother directed her to search out and talk with nurses who had worked with her late husband. The movement back and forth between living witnesses and old footage, often viewed in their own homes on laptop screens, creates an interactive path through the earliest days and into the present. Amid the diverse viewpoints of those willing to talk or who considered those days unspeakable, Domineg connected with Chizuko Uchida (1923-) who, together with the Dois and Shuntaro Hida, compose a tripartite counterpoint running through the film. The result is an unfolding exploration of silence, speaking and witnessing that tracks between these lives, with no route limited only to one life.

Overarching narrative coherence is provided by entwined evocation of the well-known dual strands of the devastation caused by the atomic bombing and of the actions taken by the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the hibakusha. The foreground is taken by the survivors themselves as vividly whole human beings, in their own words. Shigeru Doi is prominently present, not only in recollections and photographs, but through his poetry and calligraphy, held and read by his wife. In his written words and her spoken commentary, there is a gentle, moving vision of life and a world without nuclear bombs or radiation, giving a tenderness and intensity that infuses the film as a whole.

Chizuko Uchida is recognizably an activist who carefully and explicitly reflects on her aspiration to serve the military cause that had taken her into wartime nursing. Her path afterwards was one of personal healing, hand gardening of medicinal herbs and finding a voice to speak passionately against militarism, nuclear weapons and all forms of nuclear technology. In the latter portion of the film, as it engages with the Fukushima nuclear disaster, she is seen personally harvesting, drying and delivering herbs she had found helpful for the effects of Hiroshima’s radiation to those near the disaster, and opening her home to a mother and child evacuating from Fukushima. It is not only her words, articulate and persuasive as they are, but also her presence and witnessing that speak forcefully and clearly.

Shuntaro Hida had a path closer to that of Shigeru Doi, continuing in his medical work, and addressing the consequences of internal radiation for survivors of both Hiroshima and Fukushima, work he continued into his 90s. His contributions to the film extend and powerfully deepen its exploration of knowledge and of voice. His argument is not with the silence of protection and caring, but with the silencing of denial and suppression. This appears first in confronting the official denial of the effects of radiation in the years of the US occupation and the silencing of doctors and others who were working to understand its terrible and often mysteriously delayed consequences. His critique extended to the longer denial of recognition and care for those lost to or affected by radiation and what he denounced as the hypocrisy of political memorialization of Hiroshima without adequate care or genuine commitment to denuclearization.

As originally conceptualized, this ethnographic film began with an intimate focus on Aya Domineg’s grandfather and moved outward to a probing engagement of the lived experience of the first use of a nuclear bomb and of militarization. The immediate and long-lasting destructiveness is conveyed powerfully on the immediate human level of seeing the injured and dying in hospitals and in treatment. The weapon delivery in US bombers, the following military occupation and its suppression of adequate response to nuclear radiation all appear in personal and anguishing immediacy. This film goes further and excavates the preceding intimate experience of militarization in Japan, presented in the same manner as with the atomic bombing—through use of early footage of military training together with reflexive commentary by those who lived the experience. This was primarily provided by the two women, both young enough in the war years to have never known peacetime. Kiyomi Doi spoke unhesitatingly of her knowledge of Japan’s wars in Manchuria and China in the 1930s and then with the US. Chizuko Uchida was penetrating on the militarization of her school years and the depth to which it had entered her aspirations, against which she has become an eloquent opponent. She, a nurse, and both the doctors were all military personnel, further indicating the reach of the military into daily life. The recent turn toward remilitarization is foreshadowed by clips of Abe at a Hiroshima commemoration.

This conception was broadened by the nuclear disaster at Fukushima that occurred during the originally planned filming. The connections with the harm of radiation and the scale of the impact were immediately apparent. Aya Domineg extended her ethnographic approach and mirrored the earlier and longer portion of the film by combining Fukushima disaster footage with the supportive engagement and commentary of both Chizuko Uchida and Shuntaro Hida. Kiyomi Doi was extraordinarily generous and present throughout as she endured her final days of terminal cancer. The extension of the film to Fukushima carried the account beyond the violence of war to link it with the structural violence of nuclear energy and the mortal hazards of radiation, products of war and fixtures of a militarized world.

Toward the end of this ethnography there is the following passage:

Domenig: What kind of doctor would you be if you hadn’t experienced the bomb?

Hida: Well, I guess that more than half of me would be kind of the same. I can’t really compare. But even if one hasn’t experienced the atomic bomb, seeing so many people struggling on the verge of existence gradually makes one see things from their perspective.

The Day the Sun Fell weaves these intricate threads into a story of steadfast presence and witness. This is traced in the exercise and expansion of specialist medical knowledge, and in the creation of critical, engaged knowledge about the human consequences of nuclear weapons and nuclear energy. Throughout, it shows and embodies the strength of nurturance in the most terrible of circumstances.

The film ends on a gentle but not an easy note. The vision is one of a difficult and dangerous world in which to find our way, illuminated softly and unpretentiously by the lives touched in this story. There are varied ways of caring and healing to contemplate, and pathways of intentional presence to inspire. There are no abstractions or prescriptions. There is instead a resolute, questioning focus on the personal, and on each survivor living in such days. The living spurs thinking and action, with the unvoiced question in every frame: what is required of each of us now?

Works Cited:

Fassin, Didier, ed. 2017. If Truth Be Told: The Politics of Public Ethnography. Durham: Duke University Press.

Waterston, Alisse. 2014. My Father’s Wars: Migration, Memory, and the Violence of a Century. New York: Routledge.

Wulff, Helena, ed. 2016. The Anthropologist as Writer: Genres and Contexts in the Twenty-first Century. New York: Berghahn.

Ellen R. Judd is distinguished professor and professor of anthropology at the University of Manitoba. She is currently working on the political economy of access to health care and on pathways to mutuality. She is co-editor of a forthcoming volume on Cooperation in Chinese Communities: Morality and Practice.