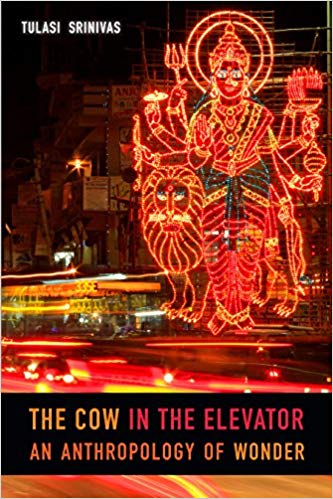

Any Western anthropologist working in India has, at times, been dumbstruck by the creative and spontaneous moments of encounter between traditional religious life and the realities of a modern global economy. I, for one, will certainly never forget hearing the sacred Sanskrit hymn Venkatachalapati Suprabhatam as a ring tone on a mobile phone, or seeing a traditional Brahmin priest, top-knotted and bare-chested in a cotton veshti lower garment and ritual poonal string slung over his shoulder, pull an ATM card from his belt while seated upon his moped. It is in the spirit of these moments of surprise and curiosity that Tulasi Srinivas explores modern Hinduism in The Cow in the Elevator: An Anthropology of Wonder. Situating her work in the middle-class Bangalore suburb of Malleshwaram, a neighborhood transformed over the last twenty years as the epicenter of India’s booming information technology industry, Srinivas chronicles life in and around two traditional Hindu temples, describing how orthodox Brahmin priests, who live according to austere, ritually-prescribed tenets, have found ways to engage creatively – and even enjoy – new technologies, vocabularies, and global perspectives in the work of Hindu temple ritual. If one will permit the proverbial “spoiler alerts,” prospective readers will be gifted with brilliant descriptions of animatronic goddess statues, the immersion of Ganesha images during the festival of Visarjan using construction vehicles, abhishekams (ritual anointing) of temples via helicopter, and the ubiquity of mobile phone cameras as a way of capturing ritually-heightened moments during Hindu puja (and yes, there is a delightful ethnographic vignette about a cow in an elevator). Srinivas approaches these snapshots of modern Indian religious life through the experiential dimension of wonder, and relates wonder to modes of traditional ritual culture, as well as emergent, neoliberal means of adapting to globalization. Life in the urbanized middle-class of India now exists largely in this dialectic, and Srinivas’ book guides the reader to the experience of living in – and even relishing – this seemingly oxymoronic world.

Srinivas deftly offers ethnographic thick description and analysis on the process of “rupture-capture,” a term highlighted in conversation with other theorists like Michael Puett, to describe the processes of living with two perspectives on modern change at once –the nostalgia, disorientation, and loss of traditional landscapes and ways of life, along with a new, often optimistic vision of modern Westernized living as utopian. She interprets the rupture-capture process as relevant even to the aesthetic worlds of Hinduism in Malleshwaram; temple rituals draw from indigenous conventions of rasa (emotive/aesthetic tropes) and rehearsed, prescribed sentiments such as viraha (separation) and raudra (anger). These traditional emotional tropes are experienced alongside modern, spontaneous, and stimulus-response evocations of emotion, like irritation at traffic jams occluding ritual procession routes, heartbroken tirades at deities for unfulfilled career aspirations, and anxiety about the incompatibilities of Hindu liturgical calendars with modern, Westernized 9-to-5 work schedules. Her compelling chapter on economies and debts invites readers to reimagine the dizzying effects of neoliberal capital in India as they are seen by the temple priesthood. Tangible units of currency like printed paper and coin, seen through the mainstream rubrics of international banking and monetary flows, are viewed by the priests as simple, colorful, shiny, and dazzling material elements, to be arranged creatively in displays and adornments to inspire wonder in worshippers, and to invite their participation in a transactional relationship with the divine fundamentally undergirded by the traditional Hindu principle of bhakti (devotion). Her work on technology in ritual and anxieties about obsolescence is also apropos in the modern culture and economy of India’s Silicon Valley; just as software developers and IT engineers worry about their innovations becoming obsolete, the priests of the Malleshwaram temples fret over their robotic puja innovations becoming passé to their congregations. On the whole, Srinivas’s volume astutely captures the joy, fluidity, and adaptability in this one locale, which swirls with currents of Brahminical ritual knowledge, information technologies, and global market culture.

The Cow in the Elevator offers a longitudinal anthropological study of Hinduism, chronicling nearly 18 continuous years of life in a Bangalore neighborhood, where numerous field informants’ places are intimately known to the author; thus, the indexing of change is portrayed in glorious detail. In the fields of South Asian studies, global studies, and economics, we have seen many descriptions and theories on globalization and the effects on culture, beginning with Thomas Friedman, but none truly offer the level of intimacy and personal analysis on religious meaning-making that this volume does. As a consummate example of reciprocal ethnography, the book benefits from the intimacy of these field relationships, and offers frank honesty and profound depth on theological discourse, shifting ethical perspectives, and emerging changes in aesthetic ideals.

As is often the case when experiencing good ethnography, readers are at times left with further questions. Srinivas talks about class, caste, gender, and ritual exclusion in Chapter 3, and while her vignettes are helpful in understanding the complex internal conflicts of the Malleshwaram bourgeois over traditional class and caste values, one cannot help but yearn to hear voices from the margins. But naturally a study like this, focusing so intimately on a carefully-delineated neighborhood temple and its constituent community of priests and upper-middle class patrons, cannot do everything, and one appreciates that within the field of anthropology of South Asia, there are others pursuing work on marginal communities’ perspectives in full-length volumes. A second area of further curiosity is in the beguiling use of Indian English to speak to the hybridity of religious culture in Malleshwaram. Srinivas often quotes her field informants’ Tamil-English or Kannada-English quips and turns of phrase to point to the theological, ethical, and cultural flexibility of their lives. Patrons paying for ritual services at the temples are asked by priests “casha carda?” (Tamil: “cash or card?”); high-earning patrons are colloquially described as “mintingu” (Kannada: “minting [money]”). To this reader, who has fluency in English, Tamil, and Kannada, these moments were both humorous and absolutely clear as a synecdoche for broader change. Non-fluent readers will hopefully benefit from these examples just as fully; further investigation into theories of linguistic hybridity might be useful here as a way of more directly foregrounding this aspect of field data.

The book absolutely fulfills its stated goals of indexing modern Hinduism in the post-IT world, and presents a grassroots – and local – study of modern Hinduism that is a refreshing alternative to studies focused on Hindutva and nationalist trends. Most enjoyably, the book reads as satisfyingly authentic to anyone who knows and loves the experience of doing anthropology in India. Fellow scholars of India will invariably hear vestiges of their own experiences of surprise and hilarity at the creative adaptations of modern culture with traditional life. Readers may also be reminded of their own moments of disappointment, anxiety, heartache and nostalgia in the field, where one sees modern innovations and a burgeoning local fascination with the Western slowly erasing the beautiful and uniquely Indian aspects of the field that we love. The central contribution of this book is its presentation of wonder as a new category of anthropological inquiry, and its interdisciplinary approach of parsing wonder from the vantage points of ritual and liturgical lives, socioeconomics, and aesthetic and creative spheres. Srinivas’s deployment of these specific categories by no means limits its readers; on the contrary, the book inspires readers to revisit their own field experiences, and look for the moments of wonder.

© Arthi Devarajan