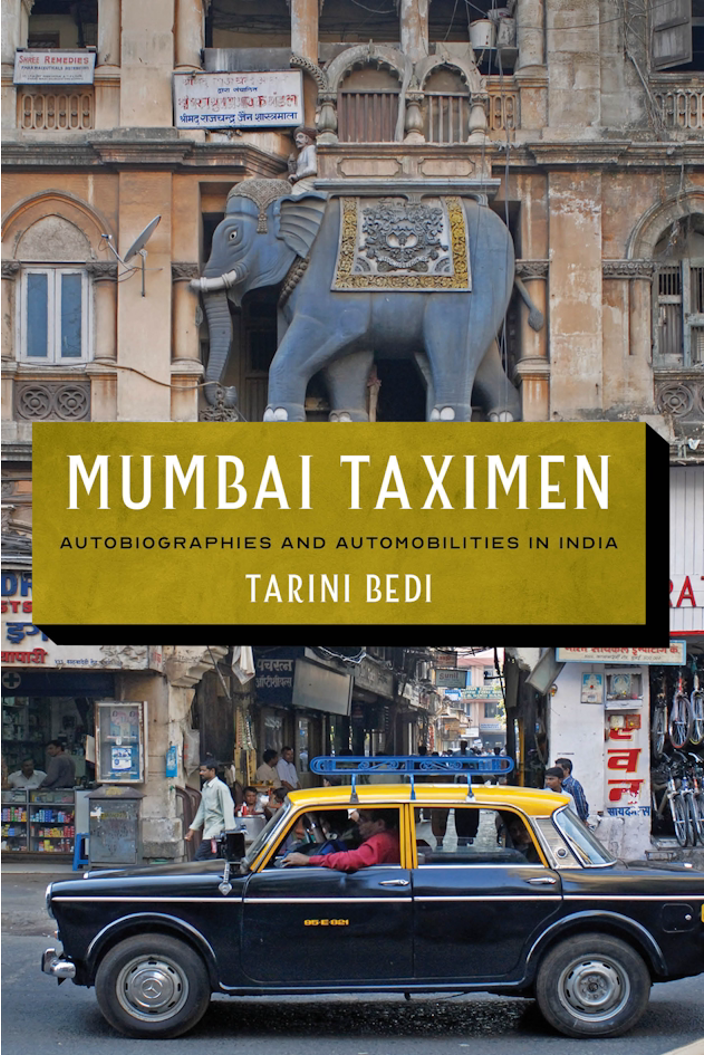

TARINI BEDI, 2022, Mumbai Taximen: Autobiographies and Automobilities in India, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 248 pp., ISBN 9780295749860

In Mumbai Taximen, Tarini Bedi holds open the door for readers to hop into a kaalipeeli taxi with her. Together, in the classic “black and yellow” Padmini taxis of Mumbai, India, Bedi and readers “follow how people make lives through driving work and how they participate in a city’s economic, bureaucratic, and political shifts amid the noise, vibrations, emissions, dust, scrapes, and bumps” on the road (9). En route, readers are introduced to several main protagonists in the chillia caste, a hereditary claim to a specific Sunni Muslim Momin kin network of male taxi drivers and their families in Mumbai who have been migrating from Palanpur, Gujarat since the early twentieth century. Bedi closely relays a story of Mumbai’s world of driving work from the perspectives of these drivers and their fabled kaalipeelis. The book’s attention to chillia drivers, specifically, and to their taxis as integral extensions of them, offers a rich and sensuously curious ethnography that pushes readers beyond classical issues of the city about poverty and the politics of labor. The fluid ecology described in Mumbai Taximen draws readers into concerns and contentions of value, care, kinship, technicity (Fisch 2018), modernity, nostalgia, and knowledge production.

Mumbai Taximen is signposted by a number of orienting questions and provocations in the Introduction that re-surface throughout the following six chapters in light of specific moments in the stories and lives of her chillia interlocutors. What do taximen’s stories of driving [in Mumbai] teach us about how urban workers inhabit, debate, and refuse change, especially when change is happening everywhere? How do taxi drivers live honorable, ethical, and sensually fulfilled lives? (4). In a mobile and migrant profession like driving work, what can we learn about kinship and locality-based relationality? What do the relational networks of chillia taximen reveal about the ways labor is differentially imagined and embodied across genders? How does a road connect people to other urban ecologies to imprint itself on the senses and bodies of those who drive for a living? (13).

Addressing these questions, Bedi works through a number of nuanced arguments to ultimately develop a theorization of what she calls Indian automobility (193). Indian automobility is presented as a postcolonial phenomenon that bounds together the working-class car culture, taxi trade, and roadbuilding that emerged globally in the twentieth century with the specifically emplaced sensorial and social labors associated with automobiles in India. The global elements surrounding this automobility take a back seat, though, in the ethnography. Instead, Bedi writes that her intentional focus is to dwell with and inhabit the immediate sensory worlds of chillia taximen on the Mumbai roads, drawing on the ideas of sensuous scholarship (Stoller 1997) from a number of anthropologists (Howes 2003, Ingold 2000, Laplantine 2015, Munn 1992).

With its wonderful attention to the sensuous, Mumbai Taximen productively channels attention to competing regimes of value encountered in driving work that are expressed through the emic analytics of joona (original, old), jaalu (web/ecology), dhandha (profession), and dhek-bhal (care), which respectively form four of the six chapters. Other Gujarati terms like dhooli (dust), ghulami (slavery), naka (crossroads), and maal (commodity) also play important roles in revealing chillia commitments and the author’s analysis of value and automobility. The glosses here offer some orientation to the terms’ meanings but a review cannot do justice to how the book closely inhabits the semiotic layers and embodied entanglements of their concepts across drivers, family members, mechanics, passengers, police officers, bureaucrats, cars, and the road. For those unfamiliar with South Asia and the polysemous usages of terms across languages, some readers may find the many terms distracting. Readers will quickly recognize, though, that Bedi’s reliance on these terms in the ethnographic writing is inspired by, if not to say accountable to, the language necessitated in her ethnographic practice attending to the open edges and ambiguities taximen shape in their daily navigations of the road.

A key anchor to Mumbai Taximen’s ecology is joona (Chapter 3), which encapsulates ideas and connotations about older people or objects. Debates around joona between taximen and police officers or bureaucrats hinge on anxieties of originality and obsolescence. Joona taximen claim their rights to the city through generations of embodied road knowledge as original drivers of the taxi trade, their service-orientation, and responsibility for the roads and its passengers as they drive their classic kaalipeelis. Officials, on the other hand, often accuse joona taximen as being stuck in the past, driving their outmoded taxis that don’t satisfy modern technological and pollution regulations mandated by the city and so-called global standards of modernity. Bedi and her interlocutors shuttle readers through the ways these tensions jam and viciously entangle questions and ambivalences of morality, subjectivity, capital, and technology.

The intricacies of the taxi dhandha (Chapter 1) and the chillia jaalu (Chapter 4) emerge out of these tangles. The profession of driving work (dhandha) occupied by chillia, Bedi shows, relies on a tightly knit, socially regulated and distributed kinship network of responsibilities and obligations (jaalu) that includes sharing cars, re/selling permits, car maintenance, loans, marriage arrangements, housing, and other forms of aid and care (dekh-bhal) for people and cars. The jaalu network of chillia connects drivers, their families, and mechanics, such that drivers are not positioned as masculine subjects individuated professionally and physically away from everyone else, but instead as one among many interdependent agents operating within the collective kinship network. In turn, jaalu offers interesting insights into gendered labor and economic opportunities, cultivations of pious chillia Muslim subjectivity, and the mutual dependence between human bodies and machine bodies, all of which would not be as evident without Bedi’s attention to the sensuous relationalities of the taxi trade.

Mumbai Taximen’s attention to joona, jaalu, dhandha, and dekh-bhal is a welcome move in a growing body of decolonial and feminist literature that thinks and feels with local knowledges and practices on their own linguistic and sensory terms. Thus, the work is an excellent example to ethnographers of one way to bridge the gap often felt between the immediacies and aliveness in the happening of research and the temporal and energetic delay of reconstructing that research through writing.

Furthermore, the book is a wonderful addition to extended studies of Mumbai’s social and material infrastructural worlds, as well as for researchers of urban labor across the globe. Of special note, with its close following of the main protagonists, the book’s storytelling is reminiscent of the microcosmic grittiness and detail of the documentary stories in Bombay Brokers (2021), edited by Lisa Björkman. Since the chapters are hyper-focused to the specific experiences of chillia drivers in Mumbai, one might be left wanting more extended engagement with other studies of neoliberal infrastructure and modern subjectivity within India and elsewhere. With acknowledgment of this opening, though, Bedi’s study is an invitation to comparative research on especially auto-rickshaw drivers’ worlds in Mumbai and other cities of South and Southeast Asia, passengers’ experiences of driving work, app-based rideshare and delivery drivers, other spaces of Muslim labor, and generally hereditary labor.

What goes unstated in the book’s introductory reflections about nostalgia is that Bedi’s account herein may very well be one of historical significance, documenting the possibly final generation of such hereditary drivers. Since the book’s publication in 2022, the joona Padmini kaalipeelis met their official, legal phasing out in October 2023.

Works Cited:

Björkman, Lisa, ed. Bombay Brokers. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Fisch, Michael. An Anthropology of the Machine: Tokyo’s Commuter Train Network. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Howes, David. Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2000.

Laplantine, François. The Life of the Senses: Introduction to a Modal Anthropology. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Munn, Nancy D. The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in Massim (Papua New Guinea Society). Durham: Duke University Press, 1992.

Stoller, Paul. Sensuous Scholarship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Drew Kerr is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research worlds revolve around cultural production (primarily poetry), the politics of feeling, senses of collectivity, and semiotics. To explore these topics, his dissertation research dwells with the contemporary social lives of Urdu poetry in urban North India.

© 2024 Drew Kerr

![]()