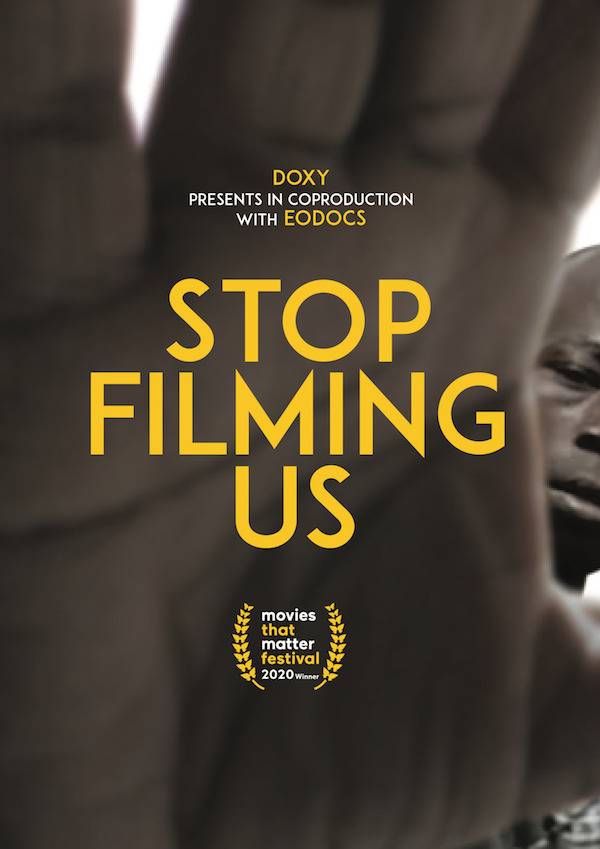

JORIS POSTEMA (Director), 2021, 95 minutes.

Link: https://www.videoproject.org/stop-filming-us.html

Joris Postma’s “Stop Filming Us,” highlights two key media: film making and photography in Goma, a city in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. As a film maker he wants to show the positive side of Goma, “despite the chaos,” going back to Goma after 10 years and wanting to show “my western image of “hell on earth,’ [which] clashed with Congolese reality.” The key question he asks both himself and the viewer is, “Can I, as a western film maker, portray this world?” Photography and film are key methods in any anthropologist’s tool kit when conducting fieldwork, and one of the key questions many anthropologists ask themselves at some point is, can they really understand the society they are studying through these mediums?

One of the overarching themes in this film is about who should tell which stories – and who has agency. Are local film makers the only ones who can tell stories about Goma or can a foreigner like Postma also tell a story, and ultimately, who controls that narrative? This question comes up several times during the film, and Postma asks his crew about whether he is being “neo-colonial,” and that question embeds a host of others, like who decides what to film, what to edit, what story to tell. However, for all Postma’s discomfort about his position as a film maker, telling stories which his film crew feel they are able to tell themselves, in the final film credits there is only one named director – and it is Postma.

Postma’s local film crew postulate the idea that the filmmaker may be part of the problem with his ‘white savior complex,’ and he is visibly uncomfortable during this discussion. TD Jack gives an example of how this works – Postma offers the crew some biscuits, asking if they want one. When approached by some street children, he doesn’t ask them if they want any, but just hands them out to them. A kind gesture perhaps, but one which robs the children of agency, and the opportunity to choose.

Then there is the story of Betty, a young, Congolese film maker which is juxtaposed to that of Postma. Betty has completed the first part of a film and is searching for funding to complete the second part. She is part of Yole’ Africa, a cultural collective aimed at empowering the youth. The centre has a large mural of Patrice Lumumba on the side. Yole’ Africa is an exhibition space where people can debate contemporary issues, and one of the debates touches on representation, and the fact that “neo-colonialism is [still] a reality [in the Congo], not a concept”:

Our perception of ourselves is still influenced by the trauma of colonialism, always being represented by others, and we never take the time to represent ourselves and decide which myths we believe and which myths are false.

Betty goes to the Institut Français to discuss funding to complete her film, and the director of the institute informs her that if she needs a laptop there is one at the institute that she can use. He then goes on to explain that the Institute exists for “collaborative” projects. The viewer never finds out if Betty does get the funding to complete her film, but the conversation between Betty and the institute director seems to suggest that the film will be completed as a “collaborative” project, i.e., with the involvement of other parties.

There are many layers to this film, and another theme which emerges around voice and agency, begging the question as to who controls the image being portrayed, is seen at the start of the film. A local photographer (Mugabo Baritegera) is called out by the people he is photographing:

“You are earning money with our photos. Why are you taking our pictures?”

Many local people are not happy having their photograph taken, and want to know what it’s going to be used for. Bartitegera says that he’s an artist, but that holds little water with an incognito intelligence officer who asks him to stop. Bartitegera argues that this is liberty of expression and as a citizen it is his right to take those pictures. He wants his photos to show how people live, and what they do – not just conflict and poverty:

When I wanted to recognize myself in images on the internet or wherever, all I saw was this negativity. So, I want to take pictures I can identify with, and that others can recognize themselves in.

In sharp contrast to this is Tor Ley, a local photographer employed by UNHCR to take photographs of the local people. They have a contract, and in it the terms of what and how Ley should photograph her subjects is clear: she cannot deviate from that. Therefore, the photos that she takes creates an image in the West of a people in permanent misery. In her seminal work “Torture and the Ethics of Photography” (2007), Judith Butler provides an analysis of which lives are deemed worthy and what merits definition as a life in the first place. She argues that we do not need a caption, or a narrative, attached to a photo to understand the context and background that is being explicitly formulated and renewed through the frame. It is not just a blank visual image, and in Goma, these images provide a deeper insight into the inequality of the power dynamics which govern the relationships between local Congolese and the 250 NGOs in Goma today. Bernth Lindfors (1999) defines ethnological show business as the displaying of foreign peoples for commercial and/or educational purposes, noting that this trope has a very long history in Europe. The display of Othered bodies, mainly indigenous people, for entertainment purposes was especially popular during the World’s Fairs during the nineteenth century. Photography and film follow along the same continuum, and two hundred years later, some things have changed, but not a lot.

This is an important film, and prior to embarking on fieldwork, this should be compulsory viewing for anthropology students. In his essay, “African’s Belgium” (2001), Johannes Fabian asks if the gaze between Belgium and the Congo can be reversed, and the imperial gaze inverted. Postma’s film shows that the Western ‘gaze’ is being contested by local photographers and film makers such as Bartitegera, Ley and Betty – but their progress is stilted by lack of funding and control over their narrative.

Works Cited:

Judith Butler. 2007. “Torture and the ethics of photography,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space (25) pp. 951-966. Great Britain.

Bernth Lindfors. 1999. Africans on Stages: Studies in ethnological show business. Indiana University Press.

Johannes Fabian. 2001. Anthropology with attitude. Stanford University Press.

Natalia Shunmugan holds a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Oxford. Besides working in industry, she has worked for the World Health Organization in Geneva, focusing on regulatory policy. There she was part of the WHO strategy team looking to develop and implement, regulatory pathways for licensing vaccines in developing countries. She currently heads up Global Regulatory Intelligence and Policy here at Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical. She is also fortunate to wear her anthropology hat at the Richmond Museum for History and Culture, where she is assisting the museum in designing an exhibit on Women’s Progress. That work focuses on subaltern voices, and recovering Native American and African-American narratives which have been obfuscated and hidden.

© Natalia Shunmugan 2022

![]()