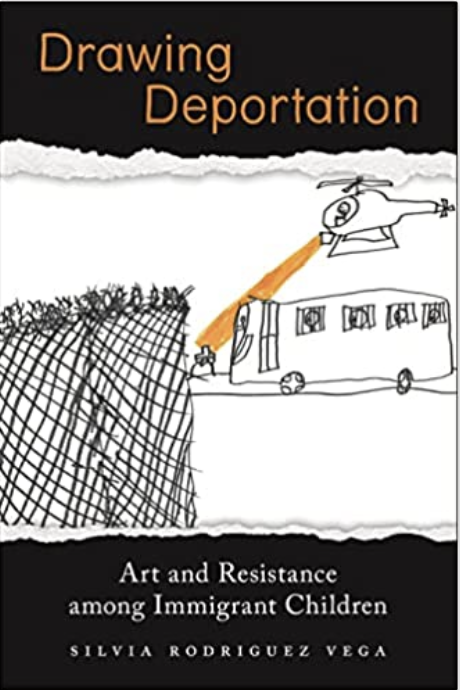

Silvia Rodriguez Vega, 2023, Drawing Deportation. Art and Resistance among Immigrant Children, New York University Press, 217 pp, ISBN 9781479810451

Keywords: immigration; deportation; childhood; trauma; creative methods.

In this compelling book, Silvia Rodriguez Vega engages with a challenging task: adding to the vast – and crowded – field of migration studies by focusing on the perspectives and experiences of an understudied social group, despite being among the fastest-growing demographics in the US: immigrant children. Due to the methodological and ethical constraints it implies, social sciences tend to shy away from conducting research with the youngest sectors of society. On one hand, the most common research methods, such as interviews and surveys, are generally conceived for adults and perform poorly when barriers such as stigma, language, and age get in the way of gathering strictly verbal information. On the other hand, working with underage populations and other vulnerable subjects increasingly requires the approval of ethical boards and committees and compliance with rigid procedures and codes of conduct. These precautionary measures are undoubtedly necessary to protect participants from any possible (intended or unintended) harm derived from the research. However, complying with such strict codes, administrative procedures, and regulations may also kill the joy of conducting field research. That is not the case with Rodriguez Vega, though: she proves to be neither shy nor looking for shortcuts. On the contrary, she embarks on a long-term journey aimed at unraveling the effects of legal violence – defined as “the various forms of structural injustice in society that directly or indirectly harm people through the rule of law” (Rodriguez Vega, 2023, p. 4), a concept she borrows from Menjívar and Abrego (2012) – on children with an immigrant background.

Building on her direct experience working in school and after-school art programs in two Latinx communities in Phoenix and Los Angeles over more than ten years, the author manages to unmask the consequences of prolonged exposure to state violence such as structural racism, detention, deportation, and family separation on the children of mixed-status families. She does that through a fine-grained methodology based on art and theatre, labeled as a praxis of art and healing, as it is meant to externalize and process trauma. Drawing, impersonating, make-believing, and other techniques are easily embraced by children and have proven to be very effective ways to channel and express feelings and thoughts that may be otherwise too complex to work out, verbalize and share with others, especially when subjects present a condition of chronic stress, as is the case for many kids in immigrant families. Rodriguez Vega shows how the cumulative effects of rampant anti-immigrant policies affect them regardless of their status or that of their parents, demonstrating once more that when state politics are imbued with the legacy of White supremacy, citizenship is not membership. The author is also adamant in stating that the antidote to chronic stress is not resilience: this is a coping mechanism that does not alter the causes of structural violence in society. Nonetheless, art can relieve the most striking symptoms, helping the subject find focus, purpose, and empowerment, and escape the “school-to-prison pipeline” (Rodriguez Vega, 2023, p. 9). Creative methods are also how she could gather a considerable amount of data not only on these kids’ excruciating experiences of border deaths, police violence, racism, and inequalities but also, and maybe most importantly, on their strategies to make sense of such experiences and imagine a future for them and their families against all odds. That is probably the main contribution of this book: in it, children are not passive victims of a system designed to keep them at the margin of society but active subjects who, if given a chance, express strong opinions, demonstrate agency, and can regain some power back through humor and creativity.

The structure of the book is pretty straightforward. In the Introduction to the volume, the reader is met with the unsettling notion that the practice of separating children from their parents, with which the world became familiar through the viralization of images of caged infants during the notorious ‘zero-tolerance’ campaign that former President Trump waged in 2018, is a well-established American tradition since the colonial invasion. In the first chapter, what follows is a general but thorough overview of immigration policies in the US from the 1940s on, something a non-American audience will undoubtedly appreciate. Notably, what the chapter highlights are the continuities, more than the discrepancies, between Democrats and Republicans when it comes to anti-immigrant policies: the criminalization of immigration, the subsequent convergence of immigration and criminal law (or crimmigration), the creation of a detention industry that profits from the mass incarceration of immigrants, and the diversion of resources from social services to surveillance and enforcement programs and bodies, such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), have been increasing tendencies since at least the second half of the 80s, irrespective of the political hue of the White House. What is maybe even more surprising to a European, progressive eye is learning that the highest number of deportations to date (over three million) was reached during Barack Obama’s presidency (2008-16), despite the general narrative that surrounded his administration and the issuing of certain protections (such as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals or DACA) granted to undocumented youth. Chapters 2 to 5 present the analysis of the rich material – mainly drawings and transcriptions of theater performances – Rodriguez Vega collected during her work in Arizona and California with immigrant children and are organized by the following themes: first is “fear” (as an outcome of the policies described in the previous chapter: family disintegration, police abuse, and structural racism), followed by “response” (of the children of Arizona to those threats, embodied by “America’s toughest sheriff” Joe Arpaio), “resistance” (of the California youth to anti-immigrant policies, notably during the 2016 presidential campaign and after Donald Trump got elected) and finally, “resilience” (reflecting how, through the employed creative methods, children were able to overcome their righteous indignation – which mirrored back societal violence – and come up with their solutions and alternatives).

After the conclusive remarks and acknowledgments, the author offers the reader a detailed methodological overview worth reading, as it provides valuable hints and guidelines for students, scholars, and everyone interested in working with subjects deemed particularly vulnerable. One of the outcomes of recent encounters between anthropology and contemporary art has been the questioning of logocentrism, meaning the prioritization of discourse and text over the visual (see Rikou and Yakouri, 2018). As visual anthropology has abundantly demonstrated, the renewed role of the visual is, at least, double-fold: it can be both the possible final product of research and a tool for producing knowledge. Here, art making is the key to unlocking meanings that otherwise, due to barriers such as language, age, traumatic memories, stigma, and power imbalance, would have probably never emerged. Certain human categories are particularly subject to be considered “voiceless”: refugees, children, victims of domestic abuse… the list is long. Research as Rodriguez Vega’s clearly shows that it is not a matter of “giving them voice,” as they already have one, and it can be strong and loud: instead, it is about being willing to change the language to allow everyone to speak.

Works Cited:

Menjívar, C. and Abrego, L. J. (2012). Legal Violence. Immigration Law and the Lives of Central American Immigrants. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 117, No. 5 (March 2012), pp. 1380-1421

Rikou, E. and Yalouri, E. (2018). The Art of Research Practices between Art and Anthropology. FIELD. a Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism. Issue 11, Fall 2018. https://field-journal.com/editorial/introduction-the-art-of-research-practices-between-art-and-anthropology

Rodriguez Vega, S. (2023). Drawing Deportation. Art and Resistance among Immigrant Children. New York University Press

Caterina Borelli is a social anthropologist who received her PhD from the University of Barcelona. She is currently a Marie Curie post-doctoral researcher at the Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, in partnership with The New School for Social Research in New York, where she is working on her project BeCAMP – Beyond the camp: border regimes, enduring liminality and everyday geopolitics in Italy and Spain (supported by H2020-MSCA-IF-2019 Marie Skłodowska- Curie grant funding, grant reference number: 898276). Previously, she conducted ethnographic research in Spain and Bosnia Herzegovina, focusing on gentrification and other urban transformation processes, urban frontiers, and internal borders.

© 2023 Caterina Borelli