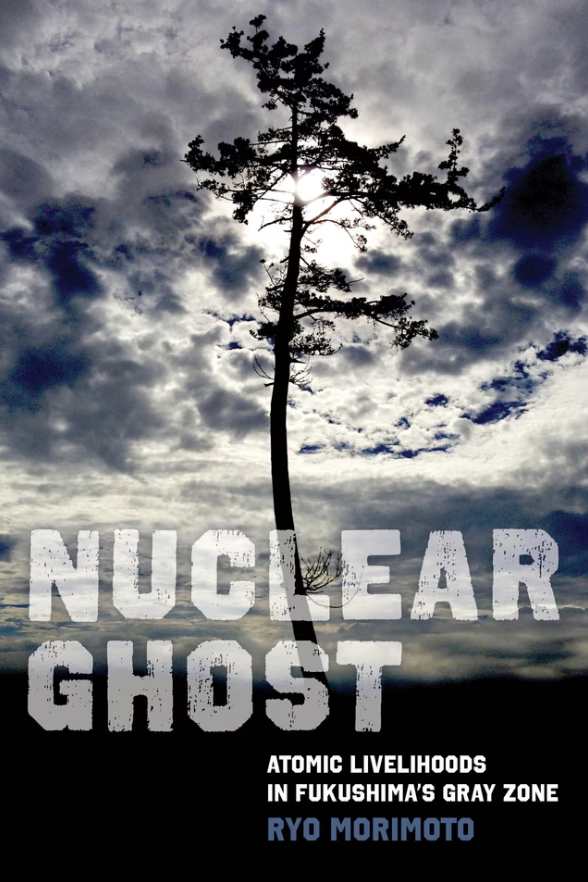

Ryo Morimoto, 2023, Nuclear Ghost Atomic Livelihoods in Fukushima’s Gray Zone, 1st Edition, California Series in Public Anthropology, University of California Press, 356 pp., ISBN: 9780520394117.

Ryo Morimoto’s Nuclear Ghost is a poignant and richly immersive ethnography that probes the interwoven lives, ongoing uncertainties, and contested landscapes of post-disaster Fukushima, over a decade after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. The book is positioned at an intersection point of anthropology, environmental studies, disaster studies, and science and technology studies (STS), and it engages forcefully with Japanese cultural and philosophical framings on risk, loss, and continuity.

The overarching hypothesis of Nuclear Ghost is that the “Fukushima disaster,” determined by Morimoto as the “TEPCO accident” to emphasize corporate responsibility, cannot be adequately understood by biomedical and technoscientific measures of radiation exposure, but instead by situated, lived experiences of people living in Minamisōma and adjacent regions. These are “gray zones” where visibility, belonging, trauma, resistance, and continuum occur daily. According to Morimoto, radiation is a biophysical agent and a sociocultural construct that affects and is affected by stories of space, history, and ways of livelihood.

At its most essential level, then, Nuclear Ghost is a radical departure from mainstream disaster ethnographies because it refuses radiation-based narratives of nuclear disasters. In contrast to a preoccupation with contamination as a measurable, medicalized danger, Morimoto turns the ethnographic eye toward what he terms “atomic livelihoods,” lived realities, coping strategies, and existential negotiations by people who decided to stay or come back to the areas contaminated by radiation in coastal Fukushima.

The key argument is that knowing about the TEPCO nuclear accident involves decentering technoscientific and state-based narratives regarding radiation in favor of noticing the multi-faceted, embodied, and at times contradictory terms in which people in cities like Minamisōma live in what Morimoto refers to as “the gray zone.” This is not a geographical term but a conceptual zone in which binary oppositions break down “safe-unsafe”, “contaminated-clean”, “victim-resister”. In this zone, the nuclear Ghost is a ghostly figure representing haunting radiation, loss, and uncertainty. It is not metaphorical but an ontological state through which people understand their worlds and futures.

The book is organized thematically into an introduction, nine central chapters, and an epilogue. The chapters are not strictly chronological; Morimoto develops concepts and narratives in ways that connect with and reinforce one another to build a palimpsestic sense of life in the fallout. The organization permits Morimoto to interlace experiences from his fieldwork, oral histories from interlocutors, cultural reference points, particularly to Haruki Murakami’s fiction and cosmologies of Japanese Buddhism, and critical encounters with theories of exposure, precarity, and affect.

Morimoto’s narrative voice seems reflexive and ethically committed, where he repeatedly interposes his mistakes and develops a grasp as a fieldworker, most notably his transformation from a technoscientific outsider with a Geiger counter to a listener sensitive to the local textures and silences. By this tiered composition, Nuclear Ghost does not provide closure. Nevertheless, it brings ambiguity, contradiction, and coexistence factors that make it an exemplar of what Morimoto terms a “social science of the surreal.”

I assessed Morimoto’s conceptual design as one of the most rewarding elements of this fieldwork research. The “nuclear ghost” metaphor contains an essential insight into how people might understand radiation: not merely something that can be weighed and measured, but an uncannily haunting presence socially mediated, emotionally charged, and temporally open-ended. This Ghost is different from radioactive fallout; it is a cultural phenomenon, a felt uncertainty, an ethical residue. In describing it, Morimoto is contributing to a larger project in contemporary anthropology to take seriously non-material or extra-scientific incidents, which has been termed the “social science of the surreal.”

Another strength of Morimoto’s position is that the book removes the narrative from state and science domination. Rather than focusing on national rhetoric, epidemiological statistics, or the state’s reconstruction efforts, Morimoto focuses on the everyday life of individuals, temple caretakers like Hatsumi, altar movers, farmers, hunters, and returnees. These people live in the literal and symbolic “in-between” spaces whose experiences are often erased in official reports and media coverage. This research reclaims ethnography through this position to challenge and reframe who gets seen and heard.

Morimoto’s deeply personal reflections on his role as a researcher from lugging a Geiger counter to grappling with his involvement in “disaster porn” through documentary work are not just self-revealing but epistemologically powerful. They provoke essential questions about academic extraction, authority, and the moral complexities of witnessing. His care in addressing the ethics of representing trauma adds depth and seriousness, particularly for readers committed to participatory, decolonial, or reflective scholarship.

Momentously, Nuclear Ghost challenges how nuclear fallout is typically visualized. Through critical reflection on tools like the Geiger counter, radiation maps, and sensationalist photojournalism, Morimoto asks readers to confront the unseen aspects of radiation and life that cannot be measured or mapped. His concept of “atomic livelihoods” is not merely a poetic phrase; it is a methodological stance that insists on holding risk with endurance, damage with commitment, and danger with the will to live and survive.

Morimoto also enters policy conversations indirectly yet consequentially in this book. While it does not hand out policy fixes, it quietly critiques Japan’s centralized approach to disaster recovery and radiation tracking. It pushes readers to consider how harm is defined, how compensation is allocated, and how certain lives that do not fit tidy victim or recovery narratives are invisible.

Despite its numerous strengths, Nuclear Ghost also has limitations, some inherent to the ethnographic form and others stemming from its theoretical paths. I assess that these limitations have no ability to diminish the book’s scientific and research value; however, they invite a deeper and more nuanced engagement with the tensions running through its methodology and scope.

Morimoto’s use of the “gray zone” concept, his conscious commitment to embracing uncertainty, strongly critiques binary thinking such as “safe-unsafe,” “victim-resister,” and “contaminated-pure.” However, while this position may be regarded as insightful, it simultaneously presents a challenge for readers not well-versed in the field of anthropology. Though an honest and often painful experience for residents of Minamisōma, ambiguity sometimes weakens the clarity of the book’s core aim.

This research also features many rich, personal narratives; however, it could have explored more deeply how gender, age, class, and social roles shape people’s experiences of displacement, exposure, and recovery. For example, women’s roles in caregiving, domestic radiation exposure, or informal post-disaster economies are only partially explored. While characters like Hatsumi are well-developed, the book avoids a broader critique of gendered labor or reproductive risk in the gray areas of Fukushima. Similarly, the labor involved in decontamination, cleanup works, or bureaucratic compensation processes could have been more fully addressed through an intersectional lens.

Furthermore, Morimoto demonstrates self-awareness about the ethical risks of extractive research, which he calls “disaster pornography.” Nevertheless, the book sometimes veers close to the same spectacle it aims to resist. Though he critiques his use of a Geiger counter and reflects on working with a European filmmaker drawn to visual drama, his position as a U.S.-based academic returning to Japan with institutional backing is not intensely interrogated.

Ultimately, this research’s intellectual intensity and cultural specificity, especially its use of Japanese cosmological and philosophical ideas such as “en,” “obake,” “innen,” “kū,” might alienate readers unfamiliar with Japanese studies or Buddhist concepts in an ethnographic text. Although Morimoto does explain many of these terms, the text assumes a significant level of prior knowledge. As a result, it may be less accessible to non-academic readers or policy professionals despite its relevance to both groups.

Reviving Morimoto’s Nuclear Ghost book is a critical experience for understanding what happened to residents after the Fukushima disaster and how Japanese culture impacted the recovery process. It lingers much like the “nuclear ghost” that shadows Minamisōma, not through dramatic spectacle or shock but by slowly accumulating feelings of uncertainty, contradiction, and an unsettling closeness to often forgotten lives. What stands out most is the book’s deep commitment to rehumanizing disaster both as an academic project and as a personal one. Instead of leaning on the language of hazard maps, risk assessments, or biopolitical trauma, I think Morimoto invites scholars and readers to witness life in all its disorder, persistence, and ghostly brilliance.

From a scholarly view, this book pushes the boundaries of how ethnography is practiced and written in the Anthropocene. It also exemplifies an anthropological approach that is methodologically reflective, politically conscious, and poetically extensive. It insists scholars or readers do not need to choose between theory and narrative, structure and story, or visibility and subtlety. Doing so furnishes a robust framework for scholars engaged in the interdisciplinary study of disaster studies, environmental anthropology, nuclear humanities, and Japanese cultural contexts.

I enthusiastically recommend this book; however, with one critical note: this book does not provide comprehensive answers related to the Fukushima disaster. It is a book about ethnographic questions, ghosts, and fieldwork priorities. It challenges us to notice what scholars and readers often overlook, listen for what is not spoken, and consider what it means to live ethically in the face of uncertainty. Morimoto’s work is both timely and essential in a world increasingly shaped by prolonged dangers, and it will help us understand the public aspect of the disaster stemming from nuclear energy. This book has the ability to impact different studies in disciplines beyond anthropology and ethnography in the future.

Atilla Kilinç is an ethnographer specializing in the energy market. He is a research associate at Istanbul Technical University.

© 2025 Atilla Kilinç