Like many other groups in Latin America, the indigenous Mixtec people of Oaxaca, Mexico have been Catholic for centuries. And like many other groups in Latin America, the Mixtec people have become less Catholic in recent decades. Although an adherence to Catholicism historically has shaped the Mixtec system of governance, patterns of economic exchange, and social interactions in daily life, many Mixtec individuals recently have converted to evangelical streams of Christianity. Mary I. O’Connor’s Mixtec Evangelicals explores the socioeconomic factors influencing this trend, arguing that globalization and corresponding economically motivated migration have given rise to this religious conversion among members of the community. Her multi-sited comparative study contributes to a growing collection of literature on ongoing religious change across Latin America.

O’Connor presents a macrocosmic view of contemporary Mixtec villages, situating them as nodes in a network of Mixtec migration sparked by globalization. In doing so, she places the phenomenon of evangelical conversion in Latin America within its broader socioeconomic context. She demonstrates that while the local consequences of conversion vary from village to village, its causes are closely intertwined with broad global trends. Mixtec Evangelicals thus provides a necessary analysis of intersections between global processes and local experiences that is highly relevant as the emerging effects of contemporary globalization continue to unfold.

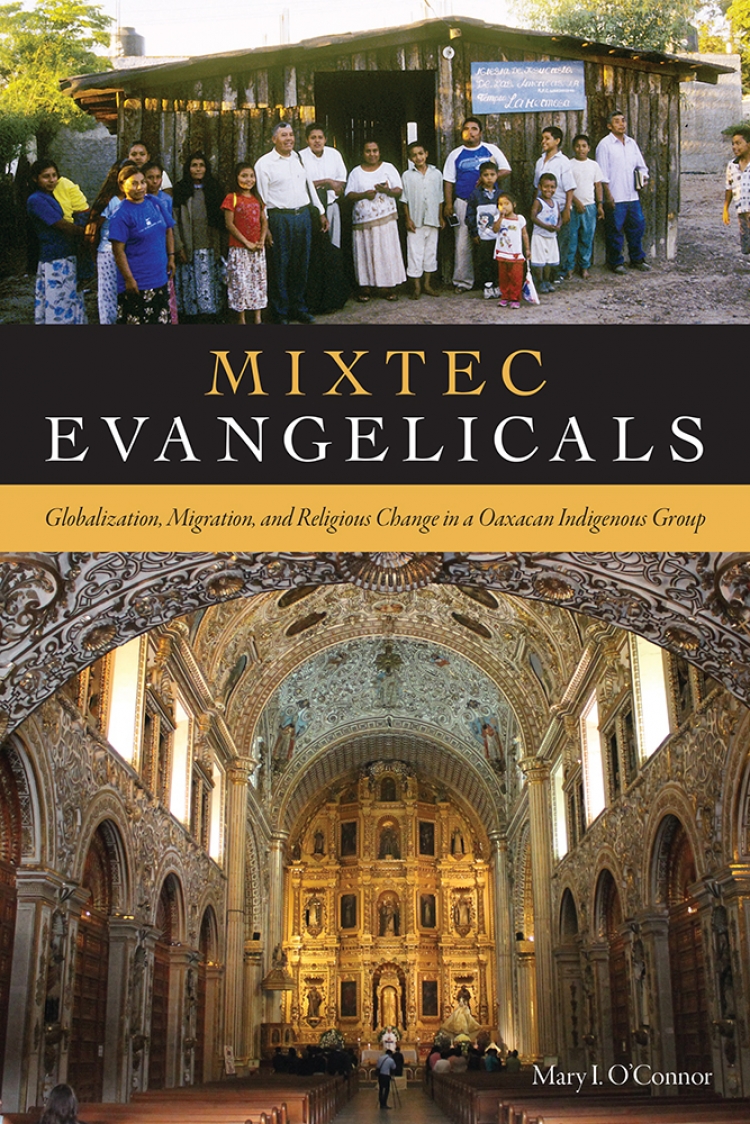

The book begins with an overview of the “Mixteca Region” in Oaxaca and highlights the established role of Catholicism in what O’Connor refers to as Mixtec “traditional culture.” Most Mixtec villages are governed by the usos y costumbres system in which each resident family is required to contribute to and participate in civil and religious duties, including the sponsoring and planning of fiestas honoring Catholic saints. It is this civil-religious system, O’Connor argues, that allows the communities to stay intact. Before Mixtecs began converting in the 1980s, it would not have made sense to separate the civil from the religious in Mixtec communities; being Mixtec meant being Catholic, and fulfilling responsibilities within the local system of governance often meant carrying out Catholic practices. In more recent decades, many Mixtecs who have become evangelical Christians have faced rejection in and from their home villages. For these reasons, as O’Connor points out, it is extraordinary that many Mixtecs have moved away from Catholicism yet have maintained both their Mixtec identity and, to varying extents, their participation in village life.

Though these villages generally remain central to the lives of migrants even after they convert away from Catholicism, the Catholics living in the villages are often unwilling (to varying extents) to fully accept evangelicals upon their return. While the migrants continue both to recognize the villages as their ancestral homelands and to financially support family members still living there, local Catholics often view the evangelicals’ rejection of Catholicism as a threat to the perpetuation of their community. Despite this conflict, when Mixtecs move to other parts of Mexico and throughout the United States, they remain rooted in their home villages both through processes of social identification and through financial obligations to their families.

The book’s second chapter provides a convincing critique of contemporary thoughts about globalization. O’Connor points out that although the phenomenon has introduced amenities such as cellphones to the communities and often has made potable water more accessible, Mixtecs and many other groups should be conceived of as “victims” of globalization. Because of international trade agreements like NAFTA, Mixtecs can no longer profitably sell their agricultural crops and thus are forced to migrate elsewhere to find employment. Of course, as is reflected throughout the entire book, globalization affects the lives of its victims in ways that extend far beyond available income sources. In the case of the Mixtecs, it affects where they live, which affects their religious commitments. This, in turn, affects their social relations with their families and home communities, the ways in which they spend money, the social practices in which they engage, and, in some cases, the structural organization of their home villages.

In the same chapter, O’Connor also challenges notions of indigeneity or the “traditional” as static. She frames Mixtecs as inhabiting “selective modernities,” as able to maintain their indigenous Mixtec-ness while simultaneously choosing to incorporate certain elements of modernity into their lives. Because Mixtec practices and systems, which are so integrally defined by Catholicism, have persisted despite the increasingly common turn away from Catholicism, Mixtecs must be regarded as modern, adaptable, and agentive rather than as inflexible and stuck in a former epoch.

The core of the book consists of a comparative study of different Mixtec villages in which members have converted away from Catholicism. It illustrates the varying reactions evangelical converts have faced in their home villages and emphasizes that each village has managed its newfound religious diversity in different ways. These varying reactions are presented as correlated with quantitative data: in general, greater numbers of non-Catholics in a given village is correlated with increased amicability, while a smaller but still significant presence of non-Catholics is correlated with increased animosity. Through this comparative approach, O’Connor importantly conveys the heterogeneity of Mixtec villages, illuminating how a single current of religious change has had very different effects across villages.

Finally, O’Connor argues that the newly transnational character of the Mixtec population has produced a Mixtec diaspora in other parts of Mexico and in the United States. As such, the book provides a window into the ways in which a diasporic community sustains its cohesion and connection to its homeland in today’s globalized world. Interestingly, the Mixtec diaspora maintains its ties to the Oaxacan villages in part through the use of cellphones, devices that index modernity-driven globalization—the very phenomenon that engendered their dispersion in the first place. O’Connor acknowledges that the longevity of this diaspora will depend upon the extent to which future generations maintain a relationship with their ancestral villages in Oaxaca; such a development, as she notes, would be an interesting subject for future study.

O’Connor places migration, caused by ever-changing global economic realities, at the center of her proposed explanation for religious conversion. While in the migrant stream, Mixtecs encounter evangelical missionaries who offer gifts, free food, and religious leadership in a place far removed from the structured Catholicism of village life. However, beyond arguing that globalization-induced migration offers a setting ripe for conversion, O’Connor does not provide an analysis of why, in fact, Mixtecs might abandon what she presents as so integral to Mixtec life. If being Mixtec meant, until recently, being Catholic, why have so many Mixtecs rejected Catholicism yet faithfully remained Mixtec? Beyond relocation to areas where evangelism has a more powerful presence than Catholicism, what has inspired so many Mixtecs to give up a religious adherence that seems so crucial to their identities? Though O’Connor poses similar questions, her answers rely heavily on macro-social trends and only minimally consider individuals’ experiences. She uses the intentionally broad label “non-Catholic,” for example, as the term “Protestant” is uncommon, but she does not address how newly evangelical Mixtecs refer to themselves affirmatively. Though it is useful to point to religious conversion as a broader trend, the ways in which it has manifested in individuals’ lives warrants a stronger focus than they are given in O’Connor’s work.

In addition, although O’Connor argues that Mixtecs select the components of modernity they wish to adopt, the actual extent of their agency in this regard should be called into question. If Mixtecs are among the groups she calls “victims” of globalization and modernizing processes, as they are forced into the migration stream to find work, to what extent are they actually sovereign over their own relations to modernity? They can, of course, choose to use cellphones or to uphold non-modern forms of local governance, but the global drive toward modernity, as O’Connor presents it, has transformed Mixtec communities in ways beyond the control of the individual or even of village leadership. Whereas Mixtec life was historically built around Catholic practices and village obligations that were fulfilled in person and without financial remuneration, the Mixtec community in the contemporary globalized world has become religiously diverse, transnational, and increasingly reliant on money. Thus it seems that Mixtecs’ entire lives have been affected by modernity, regardless of whether they are “selecting” modern changes.

In short, Mixtec Evangelicals presents an engaging macro-social analysis of some of the local effects of globalization. It ventures beyond a consideration of globalization’s socioeconomic consequences, drawing attention to its ripple effects on religious identification and intra-communal conflict. It is an anthropological work that would be of interest to, in addition to anthropologists, geographers and economists who study the effects of globalization on communities. As the religious makeup of Latin America continues to shift, the book can help point to the causes underlying these trends. Mixtec Evangelicals thus makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of the ways in which global changes reshape communities both locally and transnationally.

Work Cited

O’Connor, Mary I. 2016. Mixtec Evangelicals: Globalization, Migration, and Religious Change in a Oaxacan Indigenous Group. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Sarah Leiter is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. She is currently a Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellow studying Brazilian Portuguese. Her research interests include language, religion, and emerging religious communities in Brazil.