Lissa: A Story About Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution does not resemble a traditional ethnographic publication, but it definitely qualifies as a page-turner. Written by Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye, with illustrations by Sarula Bao and Caroline Brewer and lettering by Marc Parenteau, Lissa is the first installment in the University of Toronto Press’s new series, ethnoGRAPHIC. Utilizing the potential and appeal of the graphic novel, the series hopes to promote more collaborative, creative forms of anthropological scholarship. In his foreword, George Marcus describes Lissa as an act of transduction, conveying his own enthusiasm for the generative capacities of the project (11).

Lissa follows the intersecting lives of Anna and Layla, using their friendship to explore how individuals embody health, illness, agency, and chance in contexts of structural inequality and social injustice. Anna’s father is an American oil executive stationed in Egypt, while Layla’s father, Abu Hassan, works as the bawab (doorman) in the building where Anna’s family lives. The novel is split into three parts, Cairo, Five Years Later, and Revolution. Part I sets the scene in pre-revolution Egypt, depicting an immensely urbanized and socially stratified landscape. We learn early on that Anna’s mother has cancer, and by the end of Part I she succumbs to the disease. As they mourn their loss, Anna turns to her father and asks, “Do you think it runs in our family?” (57). This lingering question sets up the central tension for Anna’s story in the subsequent sections.

In Part II, Layla is studying at University to become a doctor while grappling with her father’s diagnosis of end-stage kidney disease. Her brother Ahmed has also been deported from a construction job in Saudi Arabia due to his status as hepatitis C-positive. Anna, who attends university in Boston, reluctantly sits in on a genetics class that eventually leads her to a Cancer and Genetics Prevention Program. After arguing with her father about the merits of genetic testing, she pays out of pocket and receives confirmation that she carries a BRCA1 mutation. While Anna contemplates the meaning and implications of this information, visiting a local “previvors” group to think through her options, the story switches back to Layla.

Making the rounds, Layla’s privileged medical school classmates denigrate the “ignorant peasants” for not seeking treatments quickly enough and refusing certain procedures (94-95). Layla’s own parents reject their children’s offers to donate a kidney to the ailing Abu Hassan. Their mother challenges the notion of a “low-risk” procedure in Egypt’s toxic and insecure environment, and transplantation disrupts the proper flow of life “from the old to the young” (108). Their father, in turn, argues that God creates the human body whole and complete. This means that a kidney is not something that one can choose to give away. Anna returns to Cairo and cannot grasp why Layla’s family does not more fully embrace the transplant as a potential solution. Layla, in turn, is horrified to learn that Anna is considering a prophylactic double mastectomy. Each friend, facing different circumstances and constraints, draws boundaries between healing and harm that the other struggles to understand.

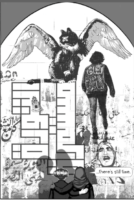

Part III begins with Anna recovering from surgery and flying to Cairo to mourn the passing of Layla’s father. She curls up with her childhood friend, and they sit together, transfixed by the laptop screen as they read reports of an Egyptian man setting himself on fire outside Parliament in Cairo. Layla catches sight of Ana’s scars and assumes that she is battling cancer, unaware she chose to pursue the preventive surgery. Political events continue to ramp up, and Layla solemnly tells Anna, “we have to make sure that what happened to Khaled Said/ … never happens again” (165).[1] Layla goes to Tahrir Square on January 25, and the next eight pages are filled with sights and sounds from key moments and turning points during the first weeks of the Revolution.

The local and global politics of sickness and suffering are present throughout Lissa, often represented through image and indirect reference. In Part III, the complexity of these embodied politics become more pointed. Anna’s presence causes visible upset at a rally, and Ahmed argues she has no right to participate in the revolution, given the United States government’s role in creating and enabling the Mubarak regime. The story also depicts various forms of injury inflicted on protesters, situating both the resulting medical crises and the actions of first responders within a broader political economy of state violence and unequal resource distribution. At its close, the narrative arc summons a hesitant optimism, but it also maintains a poignant lack of resolution to the characters’ stories and the issues they face. Hence the fitting title of Lissa, which we learn in the front matter is a colloquial Arabic term meaning, “There’s still time, not yet.”

Lissa is an eminently teachable text, and it was clearly designed with the classroom in mind. The Afterword, written by cartoonist and comics instructor Paul Karasik, discusses the relationship between artistic choices and character and narrative development. Appendix One offers a helpful timeline of the revolution, while Appendix Two features interviews with Hamdy, Nye, and Parenteau. Appendix Three provides instructors with group discussion questions and thought exercises. In addition to the timeline, Appendix Four identifies key readings and multimedia resources on the Revolution, cancer and genetics, organ transplantation, and comics and medicine. The back matter is further buttressed by a website (http://lissagraphicnovel.com/) and documentary film on the production process.

Given its readability, Lissa will generate discussions on both content and form at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and it can be used in methods courses across the board. In her critical discussion of “academic tourism,” for instance, Nye explains their decision to use the names and likenesses of real people, in addition to the work of known graffiti artists, in order to recognize the efforts and labor of Egyptian activists and intellectuals during and after the Revolution (274). A fictionalized text that interweaves the long-term research engagements of both authors, Lissa easily and compellingly transcends area studies and topical designations.

Lissa provides a bridge between different modes of thinking, doing, and representing anthropology. One need only visit the Society for Visual Anthropology’s website to note that this is part of an ongoing disciplinary push to expand beyond the monograph and text-dominated forms of knowledge production and dissemination (Errington 2018). The novel may also generate discussions in other disciplines about the contributions that ethnographic research can make to the wider world of graphic novels (Singh 2018). Lissa will start conversations in the classroom and beyond, among students and colleagues (the book has already generated several online forums and features), and I eagerly await the next installments in the ethnoGRAPHIC series.

Works Cited:

Errington, Shelly. 2018. “Lissa and the Graphic Novel Form: An Appreciation.” Anthropology Now 9 (3). Routledge: 136–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2017.1391040.

Singh, Parismita. 2018. “Lissa: A Review.” Second Spear. http://medanthroquarterly.org/2018/03/19/lissa-a-review/

© Christine Sargent 2018

[1] The images of Said’s corpse, brutally disfigured at the hands of Egyptian police circulated widely on social media, providing one of the revolution’s initial sparks.