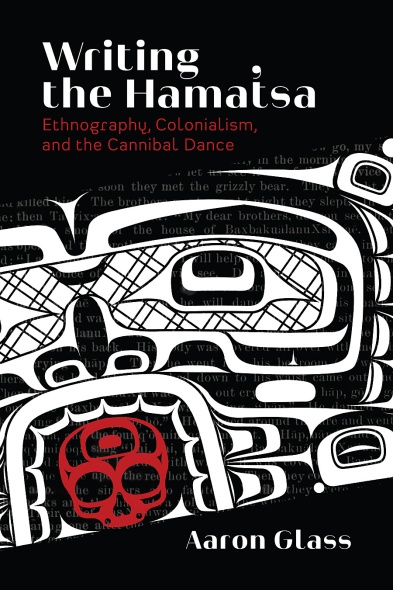

Glass, Aaron. 2021. Writing the Hamatsa: Ethnography, Colonialism, and the Cannibal Dance. Vancouver: UBC Press, 489 pg., ISBN 9780774863780

In 1884 the Revised Indian Act made First Nations peoples’ ceremonies illegal. Canada’s first Prime Minister John A. McDonald would go on to share with Parliament a number of ethnocentric messages about the spiritual condition of indigenous communities claiming that men, women and children of these communities were to be considered ‘savages’ until they became Christians. McDonald also put forth propaganda about indigenous customs claiming that First Nation traditions included the ritualistic eating of flesh and the giving away of women at traditional pot-latch ceremonies.

In Writing the Hamatsa: Ethnography, Colonialism, and the Cannibal Dance author Aaron Glass meticulously takes readers on a journey through the interpretations of cultural customs by outsiders to these communities. Glass shares how the stories of outsider perceptions to customs created racist propaganda and eventually would lead to colonial prohibition of traditional ceremonies.

Colonial attention and interpretation aggressively focused on the Hamatsa dance of the Kwakwaka‘wakw people of British Columbia. The dance was later referred to by Franz Boas as the cannibal dance. The ceremonial dance portrays the spiritual realm where a supernatural being known as the Baxwbakwalanuksiwe’ is known to capture and eat humans. The ceremonies involving the portrayal of these beings are filled with ecstatic dances, intricate masks and prescribed ritual behavior.

The elements of this ceremony within the context of the community communicate several deep philosophical teachings. The author points to a quote from an initiate into the Hamatsa: “The Hamatsa is not about what you are eating, but what is eating you” (p.41). While these ceremonies have communicated complex concepts among indigenous communities for several years, the perspectives of those outside the community and those against the community were something very different.

Glass takes a holistic approach to researching the campaigns against and the true nature of the Hamatsa. He brings us into an understanding of the cultural manifestations of this ceremony and the important rich teachings that surround the mythology of Baxwbakwalanuksiwe’. He opens with an examination of the symbolism and choreography of this much misunderstood dance.

His work then takes us into the dynamics of settler colonialism which situates us into the eventual encounters between colonialists and First Nation’s peoples. His work then takes us into the anthropological realm where famed anthropologist Franz Boas and ethnologist George Hunt began to focus on researching local community and ceremonies related to the Hamatsa. He mentions several interesting facets, including some anthropological pitfalls where generalizations made by the two may have affected future interpretations of the culture.

The text analyzes the previous ethnographic work on the Hamatsa ceremonial dance to give us an understanding of how our perceptions of the dance have changed throughout history. Lastly, Glass looks at the recent approaches to cultural descriptions from an indigenous point of view as voices of the Kwakwaka’wakw people and their views on anthropological works on their culture are documented.

One of the fascinating aspects of the cultural journey that the Hamatsa dance has taken can be found in the contemporary images of the dance. The dance once deemed illegal by colonialists is now embraced in the tourist industry in Canada. Images of the masks and dances surrounding the Hamatsa are now used in tourism advertisements and museum depictions. This brings to mind the paradoxes found in New Orleans history where African religious traditions were once feared and prohibited but today are a tremendous part of tourism and public life. What was once a private sacred ritual has become a postcard for tourism and promotion of cultural heritage.

Aaron Glass has produced an important book in Writing the Hamtsa: Ethnography, Colonialism, and the Cannibal Dance. The text serves not only as an eye-opening piece of research into the past but communicates a theme that affects us still today. Perceptions from biased outsiders toward cultures can and do affect legislation, public perceptions, and social stresses for communities.

Tony Kail (BA-Arizona State; MA-Eastern University) has served as an anthropologist in the academic, public and private sectors. He currently teaches undergraduate courses in Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Anthropology and Contemporary Issues in Anthropology. Today he serves as a curator for the Humboldt Tennessee Historical Museum.

© 2023 Antony Kail

![]()