Ending Ageism, or How Not To Shoot Old People, the latest book by distinguished age-critic Margaret Morganroth Gullette, describes ageist ideology and its effects, and proffers an array of approaches to bring about change. In this artfully composed work, Gullette focuses on the United States, the site of many of her personal revelations and case studies, while drawing on an interdisciplinary body of artistic and scholarly thought. Ageism must be taken seriously, like other isms – racism and sexism – because it is, Gullette argues, a category that is socially constructed in the same way, with equally dire consequences for humanity.

The author argues that in order for ageism to assume the full weight of attention and critique it deserves, we must first acknowledge that ageism exists, and learn to recognize it. An increase in senicide and suicide amongst the elderly around the world, often administered by rifle in the US, are but symptoms of a tapestry of suffering that touches us all in some way. Ageism lurks all around; in careless aphorisms – “make way for the young,” – and in the tacit connecting of aging with disability, mental illness, or unsightliness, amounting to ageist essentialism. We remain confused, trapped in this “peculiar netherworld” (p. 204), partly because our society, even in its efforts to do better, pursues mistaken agendas. We are told that we should fight aging, not ageism, for example; the former wrong-headed battle compounds the devastating effects of the latter. The idea of “positive aging” preaches perfection and health, much as “body positivity”, insists that there is a ‘correct way’ to go about the business of narrating ourselves. Such is the complex nature of ageism, as Gullette presents it.

Gullette goes on to describe the nexuses of ageist ideology as it is magnified and transmitted. For example, an ageist “elite”, a small group of the tech-enthusiast ilk, are now dominant in terms of the way they colonize visual culture, disseminating “billions of images colossally swarming in public space” (p.30). None of us can escape the internet, where it does often feel like twenty-something Instagram models outnumber almost any other depiction of humanity. In this consumer-focused online gestalt “food is often photographed more carefully than old people are” (p.31). Perhaps the elderly, too, should seek to resemble twenty-something Instagram models that tout similar nonsense to their age contemporaries? These observations are particularly resonant to me, as they address an important aspect of the way problems like ageism develop at this time. Those who are, like myself, so-called “digital natives”, may not have developed the visual literacy to recognize ageism unfolding in our everyday lives. While technology is not to blame per se, it is often harnessed as part of the social apparatus that propagates ageism. This book reminded me that, like the photographic lens, it ought to be more thoughtfully utilized.

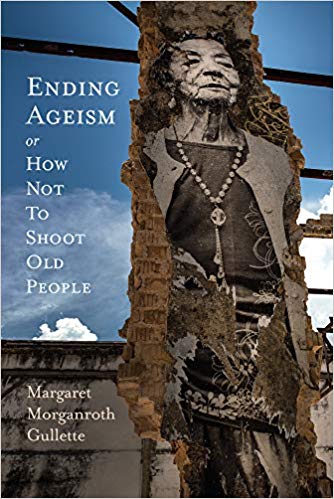

Throughout the book, Gullette emphasizes that ending ageism requires an imaginative shift, deeply rooted in subjectivity. For at the heart of it, we fear aging because we fear the unavoidable Other; our older selves. If all desire is desire of the Other, and identification and desire are two sides of the same coin, then we need to re-examine our looking, our own intimate interface to the world. How might we reinvigorate an imaginary of desire that incorporates the elderly? Turning to art for answers and solutions, Gullette has searched long and hard for images that depict aging without employing the usual clichés – abject loneliness, facelessness, a lack of context – yet still achieve the “shock of desire”, “a subject that fascinates” (p.46). She finds some, but not enough. Much of our contemporary artistic and literary output remains complicit in a careless or hostile portrayal of ageing. In the first few chapters, Gullette illustrates how and why this is so, using images of artworks to map her observations, much in the spirit of Sontag’s On Photography. In later chapters, she elaborates on the dangers that confront literary and artistic portrayals of aging. Empathy, for example, can override reason and objectivity. In Michael Haneke’s film Armour, we empathize with a husband who kills his wife by suffocation. Gullette argues that this response is strengthened through filmic device which overrides our capacity to clearly consider the rights and wishes of his wife. Viewers and critics are not educated about ageism, so they are not equipped to question the social reality presented (p.153). In a similar vein to the process of misplacing empathy, the media constructs “burden” stories that transfer the term’s meaning from caregiving work to the subject; “she is the burden” (p.143). The duty to relieve the “burden” becomes the duty to die, writes Gullette. Ultimately, such observations point to a complex poetics that underpins the language of ageism.

One of the most compelling ways Gullette illustrates ageism is by identifying and summoning the problematic personas we all sometimes embody. Many of us have been, or have known “Young Judge”, an “assertive subidentity” (p.57) who is unwilling to relate to the slightly elder, who sometimes lurks within colleges, locker rooms, or at the helm of administrative systems that dictate others’ futures, who sometimes morphs into cyber gangs to propagate hate speech (p.57). When internalized, Young Judge becomes “the bully inside us” (p.169), the voice we use to tell ourselves we are not good enough, in various permutations. Young Judge needs to be educated, to learn to see beyond the fleeting place of youth from which he speaks. An array of educative scenarios and approaches are discussed throughout the book, and addressed most directly in Chapter Three, which includes case studies of classroom interaction and dialogue, and offers techniques to combat common obstacles surrounding ageism in the classroom. This is important, the author argues, because beyond institutions, in our lived experiences of knowing our ageing families, we are all students and teachers.

While thankfully, not all of us are Young Judge, the author reminds us that we are most certainly all “eaters”. We need the food produced by our farmers, of whom a shockingly large proportion worldwide are elderly, and a majority women. In this way, Gullette links her critique of ageism to wider critiques of neoliberalism and globalization, and still manages relevant suggestions for local change. The blind spot that allows us to fear aging is akin to the devaluing of labor needed to provide for ourselves; the denial of a natural process. Recognizing ageism can help us transcend our netherworlds – be they a valley in northern California, a field in Shandong, or an urban farm in Havana – and “emerge to see the stars” (p.204).

Zoe Hatten is a PhD Candidate in anthropology with the Australian National University. Her research focuses on marriage and commercialization in urban China.