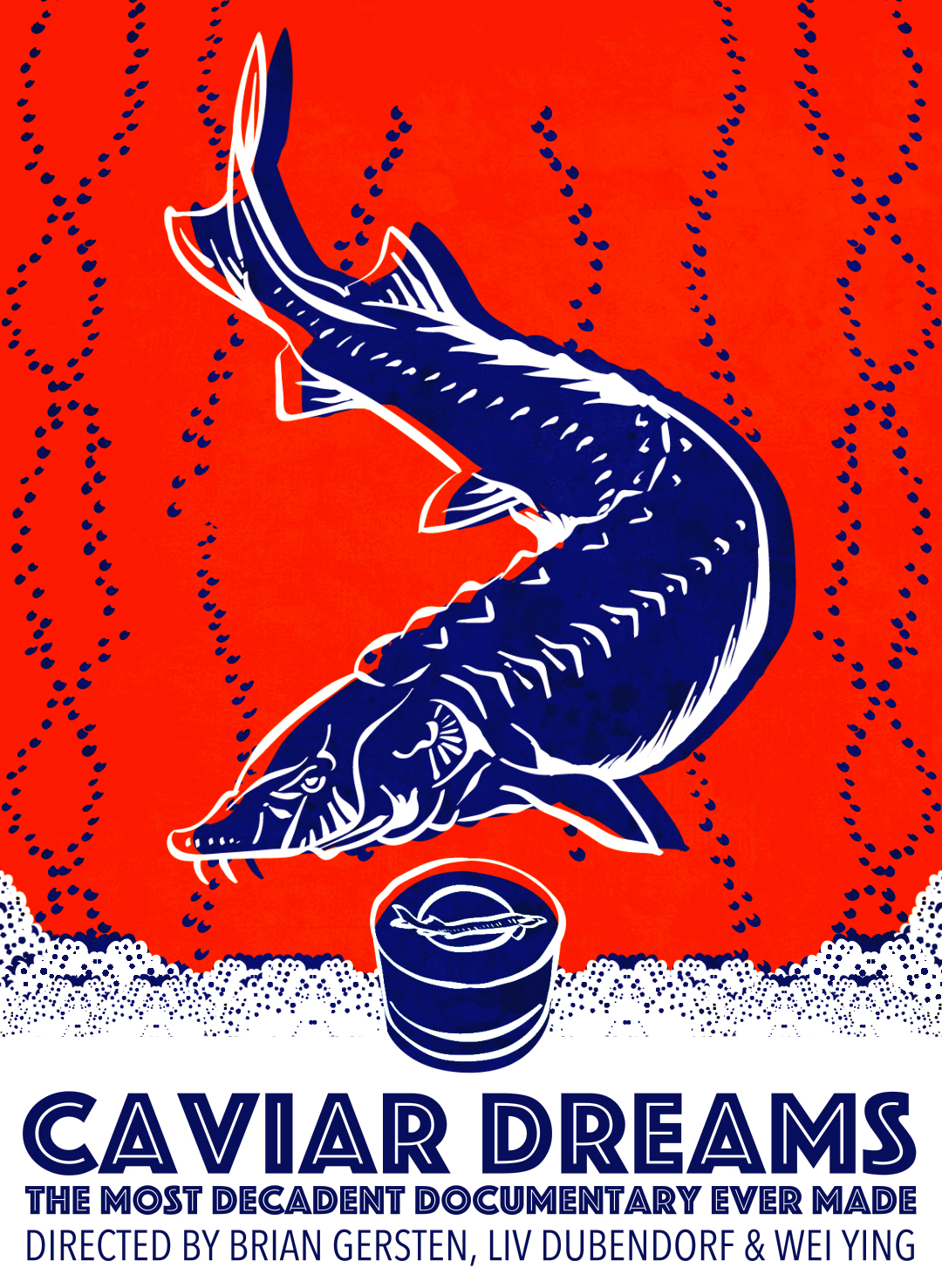

Brian Gersten, Liv Dubendorf, & Wei Ying, 2017, Caviar Dreams, The Video Project

There is little extraordinary in the taste of caviar. To the unsophisticated, exemplified in the ethnographic film Caviar Dreams by children, caviar is just “fishy.” A connoisseur might add a detail about tiny “bursts of flavor” inside one’s mouth, but the overall verdict is not out-of-this-world. Yet, many social, economic, and cultural undercurrents involved in caviar’s production and consumption propagate its extraordinariness and keep weaving caviar dreams for the public against and despite its actual taste. The “dream-weavers” of the caviar narrative featured in the film include popular movies, historians, experts on fish farming, shop owners, journalists, workers at a sturgeon farm, and ordinary consumers. The film’s narrative arc bridges medieval Russia and contemporary North Carolina and Chicago.

In the opening segment, the film emphasizes a convoluted trajectory of both the fish, whose most priced variety comes from the Caspian Sea, and its roe, which was once the food of the poor before it was elevated to the tables of Russian czars. How and why the caviar consumption got paired with a higher social status remains outside the film’s frame as the story moves fast-forward to the twentieth century’s Soviet Union and elsewhere when the demand for caviar encouraged predatory poaching and eventually led to the drastic reduction in the sturgeon population. The consumer demand for caviar, now a luxury good, and the efforts to satisfy it becomes a major theme explored by the film.

The second episode takes the viewer to a fish farm where sturgeons are raised and where aquatic culture specialists continuously seek to improve the methods of extracting roe. Here, the viewer learns about sophisticated techniques of ultrasonic scans performed on sturgeons and about the more tedious preparation of caviar done by hand in order to meet the high standards of the American consumer. The latter, as well as shop owners selling caviar, appear in the next part of the film where status finally emerges as the ultimate “product” sold together with caviar. With its flavor hardly a determining factor in caviar’s desirability, caviar sellers exploit the consumer’s partaking in the “exceptional” experience of a food item once available to nobility alone.

Here, Caviar Dreams inserts itself in the midst of competing ideologies of food production and consumption: one of status acquisition and the other of a responsible consumer. However, it is the “undoing” of the former rather than the argument for the latter that constitutes the critical charge of the film as it examines the meanings attributed to caviar within the coordinates of capitalist entrepreneurship that makes goods available, costs notwithstanding. Caviar is naturally harvested only during a particular season; yet, such timed supply runs against in the spirit of capitalism and the habit of on-demand availability developed by many consumers. Moreover, the fact that caviar is a seasonal product highlights the cultivated nature of its consumer demand. This constructedness of caviar demand, or, in the film’s parlance, the “caviar dreams” comes in sharp relief if compared to other rare food products (shark fins or bird’s nests, for instance) around which no similar mythology has been spun, at least, not in the Western world.

Culturally available forms of caviar consumption cited in the film offer further insight into the production of the social, woven into the ways in which food is prepared, exchanged, and consumed. Eating caviar on a cracker versus with a shot of vodka seems a trivial observation. The film, however, goes further to demonstrate a range of settings in which caviar is consumed, from banquets to food contests, and in which social relations are formed. In the American context, the availability of rare products like caviar is supported by the ideology of the equality of opportunity that conditions American consumers into believing that exotic goods should be available to them by the mere workings of the capitalist system.

This disjunction between availability and affordability is further underlined by references to “experiencing” caviar. Such a mindset, the film warns, facilitates the abuses of natural resources which advocates sustainable sturgeon farming. However, while the sustainable processes of producing caviar are made clear, resources needed for the narrative of a responsible consumer to win over the attractiveness of “buying” one’s way up remain less explored. In other words, while demonstrating the powerful rhetoric and sophisticated discourses that support caviar consumption as a socially uplifting experience, the film leaves it to the viewer’s imagination to figure out how the social desirability of responsible consumption could be promoted and what “dreams” the sustainably produced caviar might generate.

Additionally, in undoing the myths around caviar, the film encounters a powerful equation of cultural encounters with ethnic food consumption. Emphases on caviar “experience” suggest that some cultural “learning” might occur as people sample the “food of the czars.” Unfortunately, such hopes remain illusory. Tasting caviar teaches one little about the life of the czars or the life under them, as such “experience” locks one into the role of a consumer whose needs are cultivated in the first place to be satisfied later.

The film leaves the viewer with several issues to probe further, for example, the resources (human or otherwise) needed to transform the discursive networks and social relationships formed around caviar. Namely, what did it take to convert caviar from the food of the poor to the food of the czars and alleviate the stigmas of association with lower classes and how can that knowledge be used to transform caviar dreams once again in order to turn its consumers into more responsible, environmentally creatively beings? The film also raises a concern with the endurance of social class in the United States and with (food) consumption as an increasingly popular way of constructing social identities. Are Americans overwhelmed with status pursuits, especially in the days when social mobility has stagnated, and other ladders no longer do their uplifting work? What precisely do Americans “buy” into when they consume caviar the taste of which most people “hate” when they first try it?

Navigating the mythologies spun around caviar consumption, it is difficult for an ethnographic work to avoid myth-making of its own, often (mis)guided by its sources. One such story related in Caviar Dreams by Inga Saffron, once Pulitzer Prize winner, is the tale of the former-bounty-currently-depleted that the film-makers adopt without much scrutiny from the account of caviar availability in Moscow’s stores prior to the 1990s. While there is little doubt that the factual details of Saffron’s story are accurate, it remains patently blind to the existence of specialty shops (such as Beryozka) that catered to foreign tourists and the privileged few who paid in hard currency and could afford several pounds of caviar a month and that were virtually inaccessible to ordinary Russians. Also bypassed by the film is the story of the Delaware River sturgeon as well as the contribution to the caviar dreams sponsored by the global caviar trade from other counties that share the Caspian Sea and its sturgeons with Russia (for instance, Iranian caviar).

Finally, it is very tempting to read the story of caviar as a narrative of cultural and social change. The film urges its viewers in that direction, but it does not, unfortunately, make a bold statement on the topic. Its closing images of an eccentric food fight in a tub filled with caviar return to the outrageous habits of the new rich of the former Soviet bloc and shifts the viewers’ attention away from the status accrued by caviar in the West.

Educational Licenses for this film can be purchased through THE VIDEO PROJECT

Natalia Kovalyova (Ph.D., UT Austin) studies the relationships between discourse and power in a variety of contexts from presidential communication to academic writing. Her most recent research focuses on the role of the media in producing, maintaining, mending, or challenging social cohesion. She is a member of the National Communication Association, Rhetoric Society of America, American Political Science Association, and the International Society for Political Psychology.