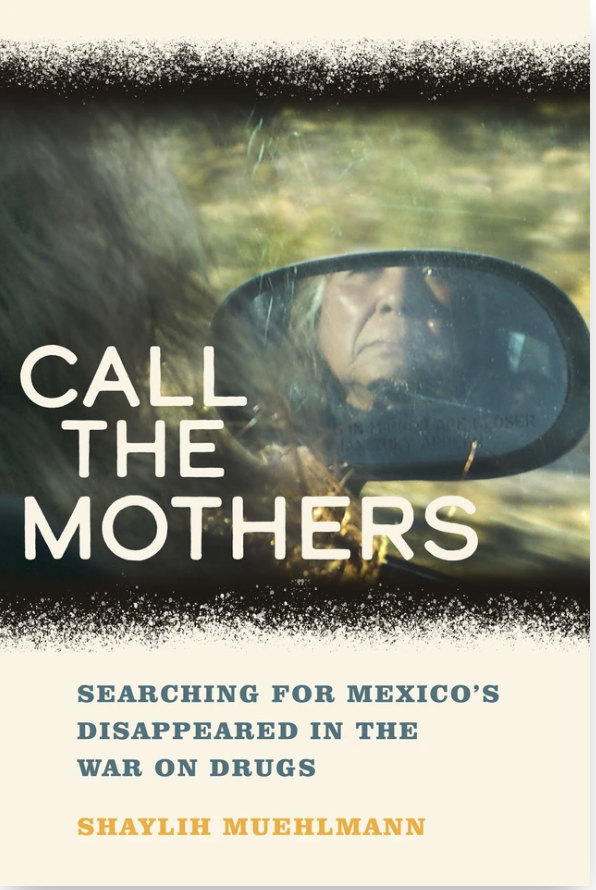

Shaylih Muehlmann, 2024, Call the Mothers: Searching for Mexico’s Disappeared in the War on Drugs, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 264 pp., ISBN 9780520314573

“Call the Mothers: Searching for Mexico’s Disappeared in the War on Drugs” is a compelling multi-sited ethnography that begins with the author’s account of meeting Leticia in Mexico City, whose young daughter, Ivonne, had been missing for two years. After undertaking a two-year-long search with minimal assistance from state authorities, Leticia finally found her daughter buried in a communal grave. By recounting this encounter, the author captures the heart-wrenching paradox of a mother’s sense of relief after finding her child dead – a devastating end to the limbo of not knowing. In five chapters, this book traces how the process of searching for disappeared family members transformed the lives of Leticia and other Mexican mothers who conducted marches, built support networks, acquired investigative skills, searched through morgues and deserts, and exposed the corruption and complicity of state officials in human rights abuses in Mexico. The core contribution of this work is a critical examination of maternal activism that unpacks its interaction with dominant gender norms, state indifference, and organized crime.

The first chapter, “They started off as a busload of victims,” establishes how the shared experience of personal loss connected women in the ‘Caravan for Peace’ rally, which started in central Mexico, and visited various locations in Mexico and in the United States raising awareness about the violence unleashed by drug policy. Through this experience, relatives of the disappeared were able to appreciate how drug policies in the US were adversely impacting both Mexicans and low-income groups in the United States and to transform the tenor of their campaigning. Prior to the caravan, emphasis was placed on the innocence of the disappeared, or their non-involvement with cartels. However, this particular framing had a limited effect, as it masked the structural causes of drug-related violence.

Muehlmann argues that this foregrounding of the innocence of their children by the mothers partially emerged from the misgivings of being seen as a bad parent, and in part as a strategic use of the figure of the grieving mother, which has a unique position in Catholicism and patriarchy. Mother-centric activism had a dual character: it enabled political action, but it also reproduced traditional gender roles. Nevertheless, its limitations were outweighed by the effects of the politicization of Mexican mothers upon their interaction with black mothers from the inner-city areas in the U.S, whose activism was centered on the systemic factors like racism and marginalization that pushed their children into crime and drugs and who framed problems in the community as issues rooted in lack of social justice.

In the second chapter, “Until we find them,” the author focuses on the wait mothers went through after the disappearance of their children. Muehlmann describes the bureaucratic limbos that the searching mothers faced and how the wait mobilized some of the mothers who founded their own search committees to investigate the disappearances thereby transcending individual activism.

There was a poignant contrast between the anguish and sense of urgency experienced by the families and the sluggishness, dismissal, and disregard with which the state bureaucracy and police responded. State authorities often employed delay tactics and blamed the victims. A grinding cycle of waiting would begin for relatives from the moment they approached authorities to report a disappearance and would continue through waiting for a formal case opening, the proceeds of the investigation, and the process of coordination between different government agencies. Long delays impeded progress and eroded the families’ well-being. Muehlmann reports on relatives selling their assets to bribe police officers or pay for the operational expenses of the investigating officers.

Intentional delays by the Mexican state included using the law to justify long-drawn waits and to exercise power over relatives. The book carefully documents the authorities’ lack of genuine political will to investigate. Weary of Kafkaesque encounters with authorities and troubled by the wait, some mothers went on to organize search collectives or launched their own investigations, at times trespassing the law. Muehlmann does not romanticize the self-initiated investigations but views them as a response to state neglect.

The third chapter, “Call the Mothers, Not the Police,” discusses the investigations led by self-organized search committees. As activist mothers became a source of support for other families looking for their disappeared children, networks and collectives sprouted across Mexico. Activist mothers offered their personal networks, insights, and skills to support other families. This included explaining how to put pressure on authorities to register cases officially, providing logistical and emotional support in searching local morgues, directly investigating murders and kidnappings, and lending leverage and connections vis-a-vis the police and criminal organizations. Although the specific character of disappearances depended on the local context, women collectives sprouted throughout the country. And given state inaction, dismissal, and collusion, newly affected families often turned to these committees for support. Moreover, the collectives began to push back against the authorities’ policy to underplay the number of the disappeared. Muehlmann notes that although women-led collectives filled in for incompetent state institutions, they lacked resources and professional competencies. This is framed as the effect of the neoliberal thrust to shift state responsibilities onto civil society while state-society relations remained conflictive.

The fourth chapter, “A rage so fierce she didn’t notice her feet,” investigates the impact of officials’ dismissal of victims and their complicity with organized criminals. Through a detailed account of a public confrontation that went viral on the internet between a mother and the Veracurz governor Duarte Javier, the author unveils the longstanding nexus between organized crime and public office. The alliance of high–level public officials and narco-traffickers in Mexico goes back in history and cemented the accumulation of many private fortunes but this informal arrangement was unsettled by neoliberal reforms and power transition in the 1980s. The author shows that beyond the war on drugs, militarization and violence were linked to trade integration (NAFTA) and US-Mexico security cooperation (Merida initiative). The author provides this context for drug violence and overcomes personalistic characterizations of corruption.

The final chapter of the book, “Without a body there is no crime,” traces the discovery of mass graves and the implications for relatives, civil society groups, and the Mexican state. The unveiling of these clandestine burial sites – despite attempts of obfuscation and frequent denial of the disappeared by the state—demonstrated the gravity of the situation, although it did not lead to a more transparent investigation by the officials. Nonetheless, for the relatives, the discovery of remains of the missing provides irrefutable evidence of the crimes committed.

In another development, new information about the location of mass graves has come from the cartels themselves. The author argues that criminal groups strategically conceal or alternatively draw attention to crime scenes such as mass graves, for instance, to signal their control over a certain territory. But mothers also received tip-offs from low-ranking cartel members, leading them to develop a more sympathetic view of these cartel members compared to state officials.

Muehlmann examines the pathways of affect in these paradoxical sympathies and rejects the oft-cited trope of glamourized narcos. Instead, the author offers a more convincing reading of this sympathy to the profound hurt caused by the denialism and obfuscation of state officials’ denial: relatives felt they were more likely to get help from the narcos than from the state. The author concludes by noting the significant achievements of the civil society movement, led by mothers, that formulated demands for justice for the disappeared without needing to foreground their ‘innocence.’ Written in an engaged and accessible manner, the book reveals the experiences of women searching for their missing relatives and the broader political economy that produces and sustains drug-related violence. Given the rise of women’s activism, the book offers novel insights into the literature on forced disappearance, social movements, and neoliberalism with implications far beyond the case of the war on drugs in Mexico.

Hammal Aslam is a PhD researcher at The International Institute of Social Studies. In his doctoral work, he is focusing on rural transformations in Balochistan, Pakistan, with a specific focus on changes around livelihoods, labor, and natural resource use and access. Previously, he worked as a university lecturer in the Department of international relations at BUITEMS, a public university in Quetta.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Helena Perez Nino for her guidance in editing and revising this article. I am also grateful to Rassela Malinda for reading an earlier version and providing valuable feedback.

© 2025 Hammal Aslam