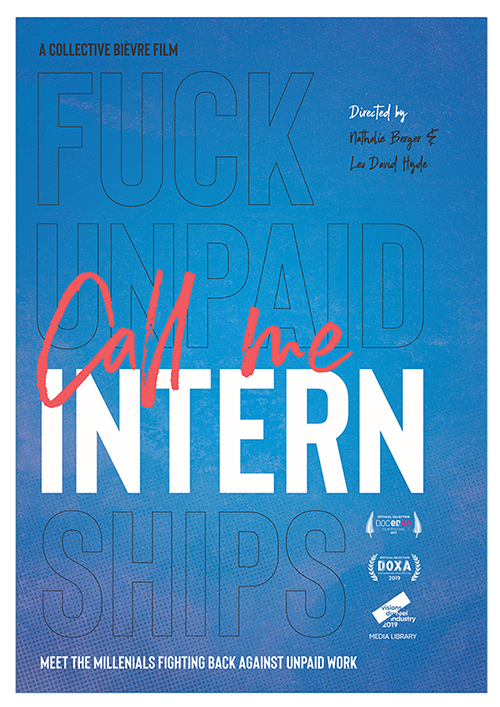

Nathalie Berger and Lee Hyde (directors), Call Me Intern (2019). The Video Project

Article 23 of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that:

Everyone without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration.

This was David Hyde’s final statement to the press, at the conclusion of the documentary Call Me Intern by Nathalie Berger and David Hyde (2019). Three interns had the courage to speak up about their working conditions, rather than just “keeping their heads down” and then stepping into a salaried position after their time of unpaid labor. Their actions led to the creation of the Global Intern Coalition with protests and strikes each February 20th, which encourages interns to know their rights, know the law, and know what remuneration they are entitled to. Although being paid for one’s work is a key driver of these protests (which has the support of the European Parliament), the documentary exposes far more.

David Hyde (United Nations, Geneva), Kyle Grant (Warner Music, NYC) and Marisa Adam (Obama’s re-election campaign, Chicago), highlight the normative unfair labor practices across many organizations, which hire interns to work without pay. It is expected that interns are able to support themselves, that they are able to provide for their own accommodation, transport, food, visas, and medical insurance costs for periods ranging from 3 months upwards. A more traditional understanding of an internship is that it is an opportunity to get a foot in the door, a stepping-stone to jump-starting their careers. David, Kyle and Marisa’s experiences expose the vectors of race, class and privilege which form the backbone of internships, and intersect with themes such as inter-generational inequality, low social mobility, and the growing global social and geographical divide. These interns highlight the urgent need to change the way internships are awarded by making them paid opportunities that are truly open to all – a ‘democratization’ of internships – which would change the power dynamics around policy making. It could mean that there would no longer be photos of Paul Ryan and the White House interns – who are all white – except for one Asian man, going viral on Twitter. These key issues lend themselves well to an anthropological analysis that looks at the interplay of power and politics.

“If you can get people to work for free, why wouldn’t you?” is the question raised by white, middle-aged, middle-class men during the documentary. These attributes alone opened many doors for them, without too much effort. And then there is Andersen Cooper, son of Gloria Vanderbilt, ridiculing interns for wanting to be paid for their work. Kyle and Marisa are African-American, and both have had negative experiences during their internships. Kyle’s internship was terminated within two months of starting at Warner Music, whilst Marisa was downgraded from intern to a “volunteer opportunity” within three months of her starting with Obama’s re-election campaign. Not only was Marisa the only African-American female in her office, but her reports to HR of sexual harassment fell on deaf ears. Kyle had to deal with homelessness and slept at a shelter during his internship, making the point that he’s both “unpaid and homeless,” and that “you feel one side of America during working hours, and outside there’s another.” Both these interns did not conveniently find a place at the internship table, and their journeys are fraught with obstacles. Foucault argues that power is contested (1980), and there is a shift in the narrative when Kyle becomes the named plaintiff in a class action lawsuit brought by the unpaid interns against Warner Music; and Marisa writes letters to Obama about her harassment and goes on a seventeen day hunger strike – a sharp change from “not rocking the boat,” and just getting on with things.

Shore and Wright (1966) argue that concepts such as “family” and “society” are treated as ideological and political concepts, but “policy” is still treated as though it were politically and ideologically neutral. Indeed, a shift in policy making is needed – but for this to occur, the internship process needs to be democratized, and people need to be paid for their work. The documentary makes clear that if internships are only accessible to people who are able to support themselves because they are from wealthy families – “what happens is that you only have well-off white people making the policies.” You end up with a small group of people who are increasingly disconnected from society, creating policy, and reproducing power relations (Foucault 1980), which will contribute to even greater social and geographical divides across the globe.

As anthropologists, we should not be afraid to “plunge into the vexed issues of modern societies” (Eriksen 2006), and tackle issues of human rights and unfair labor practices. The documentary shows that change will not come from the top down, and that young people need to organize themselves and fight back. The response from the UN, one of the most powerful organizations in the world was: “Geneva is expensive – unless you planned things well. We’d love to pay our interns but we can’t. There’s a general assembly resolution which prohibits us from paying you.” This reaction should not be surprising: power has many layers and privilege replicates and favors those already privileged. The documentary calls for internships to be opened to “100% of the population”; and that people should not be “disqualified by being born to the wrong parents.” Indeed, internships should not be accessible to the privileged few – there is too much at stake. Policy is key to shaping global power relations, and forcing change will mean that modern power constructs can be challenged and the world re-shaped.

This film provides a powerful insight into what it means to be an intern in the 21st century. It highlights the fiercely competitive nature of internships, who has access to them, and who gets left behind. Although all three protagonists were successfully awarded an internship, the reality of what that internship looked like and meant, was very different. In anthropology, film is sometimes seen as a way to convey a snapshot or a quick view of a culture. Rarely is ethnographic film perceived to be a ‘game-changer’ which influences the theoretical debates in our discipline. Although this is not an “ethnographic film,” this documentary challenges that assumption, and lays bare the power structures governing access. Being multi-sited, it does not present a frozen moment in time which locks the protagonists into an “ethnographic present” (Fabian, 2002); but is dynamic, and has led to a global mobilization of interns, with the formation of a coalition for intern rights. The documentary lays bare the different inter-generational approaches to the work culture, and show how that is rapidly changing seen through the eyes of Millennials. It is an important film for so many reasons, and everyone should see it. However, it will be especially interesting to anthropologists who want to understand the construction and replication of power, as well as how power is contested and challenged. It documents impressions, perspectives and realities of an intern culture that is in the process of defining itself.

Works Cited:

Chris Shore, Susan Wright. 1996. Introduction, In Chris Shore, Susan Wright, eds., Anthropology of Policy: Perspectives on Governance and Power. Oxford: Routledge.

Johannes Fabian. (2002 [1983]) Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Michel Foucault. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. Toronto: Harvester Press.

Thomas Hylland Eriksen. 2006. Engaging Anthropology: The Case for a Public Presence. Oxford: Berg.

© 2020 Natalia Shunmugan

Natalia Shunmugan holds a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Oxford. Besides working in industry, she has worked for the World Health Organization in Geneva, focusing on regulatory policy. There she was part of the WHO strategy team looking to develop and implement, regulatory pathways for licensing vaccines in developing countries. She currently heads up Global Regulatory Intelligence and Policy here at Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical. She is also fortunate to wear her anthropology hat at the Richmond Museum for History and Culture, where she is assisting the museum in designing an exhibit on Women’s Progress. That work focuses on subaltern voices, and recovering Native American and African-American narratives, which have been obfuscated and hidden.