AIJAZI, OMER. Atmospheric Violence: Disaster and Repair in Kashmir. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024. 281pp. ISBN 9781512823622

Keywords: Ethnography; radical humanist anthropology; disaster studies; affect theory; decolonization; conflict; borderland.

Lata Mani (2022) reminds us that our task as anthropologists is to represent and interpret a world that is infinitely messy, playful, mysterious and magical. Omer Aijazi’s first monograph upholds this potential. Engaging with the afterlife of environmental disasters and armed conflicts, Atmospheric Violence stands as a searing witness to an alternative form of living in Azad Kashmir, or Pakistan administered Kashmir.

In an atmosphere of chronic violence, the borderland in Aijazi’s lyrical work features as a conglomeration of movement, intensity and affect. The militarized, ecologically brittle valleys or the mountainous periphery where the ethnography is based becomes the center of life. A form of life that people continue to live despite the atrocities, formulating and reformulating their own politics of breath. Addressing all the writers, dreamers and the world makers, making this his heart work, Aijazi puts critical studies of disaster in conversation with radical humanist anthropology, black studies, indigenous studies, affect theory and Islamic philosophy. This kind of scholastic tapestry is a breath of fresh air. Breaking the obsession with area studies, establishing cross disciplinary dialogues, Aijazi looks for the political in the intimate every day.

Moving away from the grand narratives revolving around the nation state and the sovereign citizen, Aijazi launches an epistemic disobedience. Flowing from one fragment to the other, fragments that make and break lives, locating theory in the flesh, Ajazi attempts to dismantle the myriad hermeneutical injustices that the social sciences are inundated with. Using a decolonial approach to disaster studies centering not on trauma but repair, Aijazi grapples with multiple forms of violence. Immeasurable forms of violence that are foregrounded in the mountains in and through the textures of the ordinary. Illuminating these miniscule textures, this magnificent ethnography immerses the readers into the precarious lives of the people in the borderland. These are lives that are lived in a state of debilitating fear and world annihilation.

Uncommonly beautiful and mortally dangerous is how Azad Kashmir comes alive in and through Ajazi’s pen of immense might. He thinks collaboratively and across traditions, weaving an intellectual assemblage, shattering the normative episteme conditioning Kashmir studies. Replete with various kinds of scholastic drifts ricocheting between various kinds of belonging and non-belonging, this book embodies a creative contradiction. This contradiction is both – of life and of anti-disciplinarity. Commanding a wide breath of scholarship, Aijazi shows that his interlocuters attempt to live despite the world. They refuse to accept the norm and forge a life in and of contradiction.

Seamlessly blurring the stringent divides between theory and activism, inside and outside, fact and fiction, for Aijazi, knowledge production becomes a form of attunement rather than capture. Shunning the dominant discourses on Kashmir revolving around geopolitical territories and security analysis, Ajazi marvelously documents the alternative memories and aspirations of Kashmir, steadily nestling in the crevasses of the mountains.

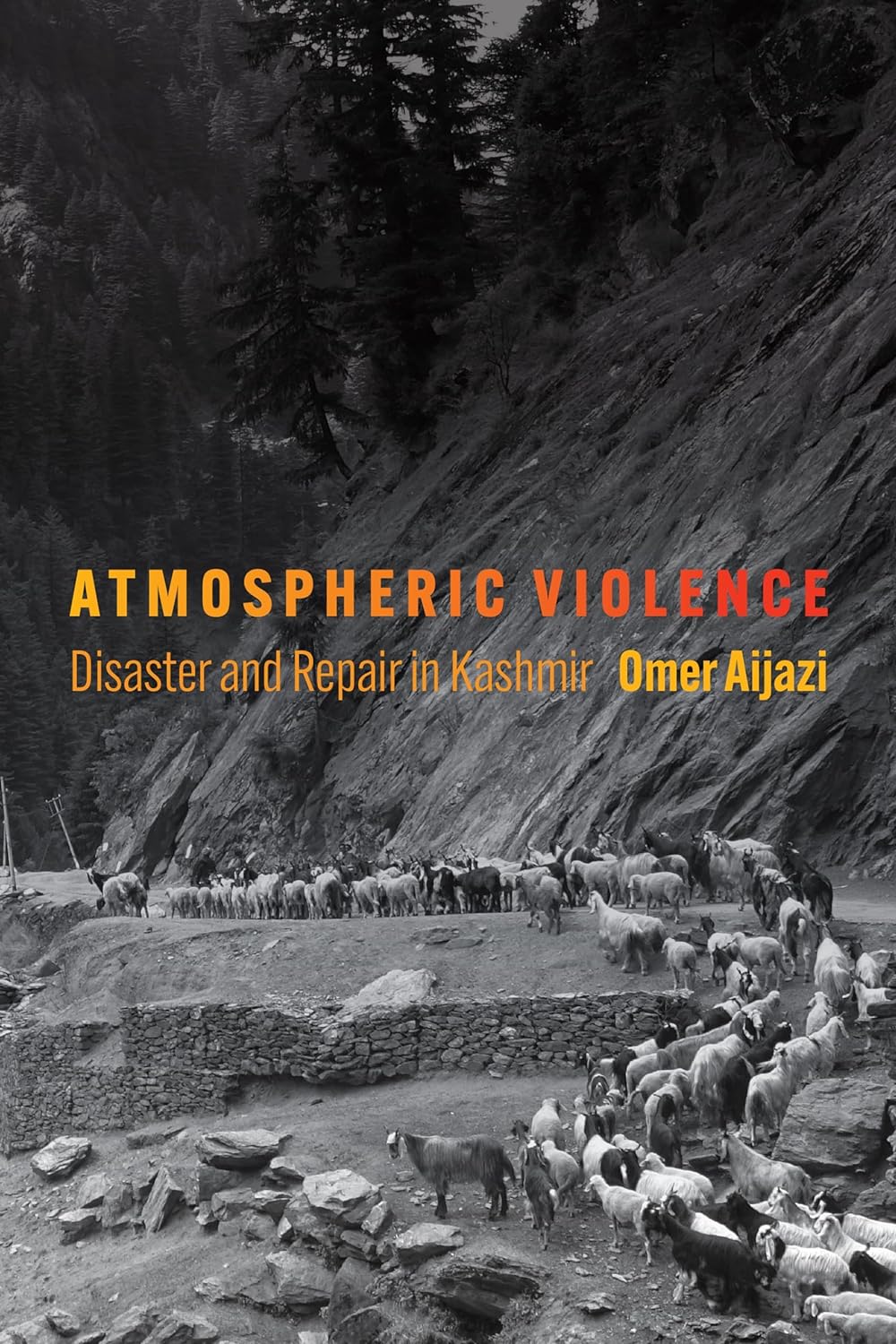

In this work, the ordinary throws itself together out of forms, flows, powers, pleasures, distractions, drudgery, denials, practical solutions, shape-shifting forms of violence, daydreams and opportunities lost and found. Braiding a humongous range of theory with ethnographic vignettes, Aijazi organizes the book in five scenes- relational instances where a text is connected with another and the self is connected to the other. Seeing and feeling the intensities of the ‘other’, abundantly using photographs for the reader’s sensory delight, Aijazi introduces us to five scenes. Featuring five protagonists, there are scenes- of betrayal, of kindness, a scene of friendship, a scene where ugly feelings feature and a scene on opacity or refusal.

In the first scene, where Aijazi intertwines form and content, we meet Niaz, an aspiring school teacher, whose failed body refuses to recover just like the disaster- stricken landscape. Niaz disrupts the synchronicity of the present, betraying it, opening a future that evades it. By refusing repair, Niaz dwells in the interstices, opening up an alternate ontology or a modality of life. Loss is not the only ramification of violence in Aijazi’s work. Locating violence in the mundane every day, this deft ethnography churns out the generative potentialities and the redeeming aspects of life amidst violence.

In the second scene, Aijazi introduces us to Parveen- a midwife who makes her way to the clinic every morning. She hopes her deceased husband will be blessed if she continues with her hard work of serving others. Kindness becomes her modality of being, a set of ethical relations that revolve around compassion and a life lived well together with others- both visible and invisible, creating an alternate sociality.

The elderly Sattar Shah and his friendship with god imbricates the third scene. A polyvalent character, Sattar Shah reconciles immanence and transcendence through his poetic knowledge and spiritual longing. Once again, through Sattar Shah’s narrative, Aijazi effectively breaks the binary between this world and a divine elsewhere. Following scholars like Leela Fernandes, Schileke Samuli and others, Aijazi effectively decolonizes the divine giving us a fecund space for thinking sacred subjectivities and metaphysical yearnings anew.

In the fourth scene we meet with an irritated Abrar. Abrar’s exasperation is materially grounded in his lifeworld. Aijazi names Abrar’s ongoing frustrations as minor anger. Minor anger draws much needed attention to the frictions arising from a form of life that is destabilized by fixed sovereignty of any kind. Rendering singular sovereignty non-operational, Aijazi shows how minor anger or ugly feelings in everyday gestures compel for an ethical urgency. Succumbing to this ethical urgency people often engage with those elements that impede the daily flow of life. In this chapter, Aijazi incisively argues that such engagements often generate an alternate way of living instead of being counterproductive to life and flourishing.

Chandni bibi enters in the last scene. She survives at the end of the world refusing a unilinear representation, clamoring for opacity. Opening up to the discrepant possibilities that the perilous everyday has to offer, Chandni bibi like Sattar Shah and Niaz inculcates an expectation from life that no one can satisfy. Aijazi terms this as sovereignty in the making and I call it fractured sovereignty. In this web of expectations, nothing is final or stable. There is always something that is yet to come- an element of wonder. Throughout this endlessly generative book, Aijazi tells stories that restore our belief in wholeness or entanglements incorporating both- life and non-life. These are stories of resilience. Stories that restore our faith in the human kind. Merging the ethical and the political in a geo-politically disputed area, Aijazi brilliance lies in disturbing the sovereign subject in and through the practice of breathing and kindness. Kindness puts the breath back and breathing sews myriad relationalities, conditioning kaleidoscopic life worlds.

Omer Ajazi’s writing is poetic, radical and uncannily perceptive. His work will deeply resonate with scholars interested in knowing life in its entirety, life amidst chaos and ruins. A political necessity, Aijazi’s book holds valuable insights for anyone who breathes. It’s a rarity and a pleasure to encounter this kind of scholarship that oscillates between heartbeats and heartaches. This is the kind of scholarship that continually simplifies the self and amplifies the other, healing our souls, shaking our mind-hearts.

WORK CITED:

Mani, Lata. Myriad intimacies. Duke University Press, 2022.

Akashleena Basu is a PhD student in the department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

© 2024 Akashleena Basu

![]()