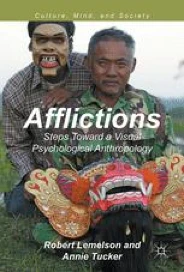

Lemelson travelled to Indonesia in 1996 to carry out his doctoral research on the influence of cultural contexts on the experience and trajectory of mental health, and to explore and better understand some of the questions raised by the World Health Organization (WHO) research conducted in the 1970s. It was during this fieldwork that a friend with a degree in anthropology came to visit him in Bali. She filmed him working in the field and collected about forty hours of filming; material that remained unused until Lemelson presented segments to his students and observed all the interest generated. In 2009, he hired Annie Tucker as a research assistant and writer to help develop a study guide for films. The six ethnographic films in the “Afflictions” series are at the heart of “Afflictions: Steps Toward A Visual Psychological Anthropology.” This book is intended to complement the stories and themes explored in the films, and to shed light on the contribution of ethnographic film to psychological anthropology.

The first part of the book, “Steps Towards a Visual Psychological Anthropology,” presents the advantages of and interest in ethnographic film, such as the transparency of the fieldwork and access to emotions and intersubjectivity. This section also discusses the possibility of integrating ethnographic film with psychological anthropology, particularly with person-centered ethnography. The authors provide a history of the use of visual material (photography, drawing, film) in anthropology as far back as the late eighteenth century and present precursors such as Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson whom they believe were the first to have explicitly used visual material in the field of psychological anthropology. The last chapter discusses the lived experience of culture and mental health in Indonesia. It provides several explanatory elements on culture in Bali and Java, such as the perception of people with mental health disorders, the socio-cultural aspects of recovery and the centrality of spirituality.

The second part, “Afflictions: Culture and Mental Illness in Indonesia,” presents the six people who took part in the filming of the series “Afflictions.” This allows the reader to have a global idea of who those people are, their social, cultural and economic situation, and a chance to learn more about the context in which the first symptoms of mental health disorders emerge, its forms, manifestations and repercussions both for the people and for their family and the community around them. We learn about caste functioning in Indonesia, social representations, and socio-cultural and gender norms. Three of the subjects have a schizophrenia disorder, while the other three have neuropsychiatric disorders. These chapters allow us to understand the trajectory of each person in their recovery. The “Outcome Paradox” term used by the WHO is also revisited, and although each case observed is different and complex, there is an overall observation that the recovery of these people was based more on socio-cultural factors than on biological or psychopathological factors.

The last part, “The Practice of Visual Psychological Anthropology,“ introduces concepts such as ethics and participant consent. Although people living with severe mental health disorders may be vulnerable, Lemelson has surrounded himself with a team of local specialists to closely monitor each of the participants. Their consent was assured throughout the process, and this team was present when needed if trauma was rekindled. This team has certainly also played a role as a cultural mediator. The scenes had to be accepted by the participants before they could be included in the series. The (positive) reaction of the community was also a validation element. This section also explores the requirements for ethnographic filmmaking, as well as the particularities, the types of equipment (which presents very precise information on the material to use), the management footage (the recording of information), production, the technical aspects of filming interviews, editing and storytelling, collaboration and intervention, compensation and ethical issues and the importance of local employees.

On this subject, the author is very aware of the reticence surrounding ethnographic film; there are certainly reticences among several anthropologists to film in their field of research. Indeed, fears such as those of staging, of losing authenticity by recreating a moment, of the visual being altered by subjectivity, and of the habit of field notes being lost. Although ethnographic film is a medium that is little theorized and for which many anthropologists are still reluctant to use, it is becoming increasingly essential to address the question of its usefulness and use, particularly in light of the increasing accessibility to technology. Whereas just twenty years ago, filming in 16mm and having a video editing system cost a fortune. The advent of 4k via smartphones, for example, and free editing software are making field shooting more and more accessible.

The ethnographic film should always be accompanied by a form of explanation, whether at the level of the narrative, a discussion following the screening, or a book; which in this case still testifies to the authors’ desire to give a complete vision of the phenomenon studied. The strength and impact that the image can have on a general audience must be considered, although the written word is not immune either. Very few ethnographic films on the subject of mental health have been made, possibly for ethical reasons related to vulnerable populations and the fear of biased understandings that might contribute to the reinforcement of their marginalization.

The book is not only relevant and informative on the subject of visual anthropology, but it is also very concrete: Lemelson provides many examples of his own experience and that of other researchers, which helps to make the book practical. In addition, Lemelson has impressive field experience, his data represent nearly 12 years of research using the Person-Centred Ethnography method, which is “both a methodologically and theoretically distinct process from other forms of interviewing and data gathering in anthropology” (p.9). He always kept in mind how the subjects could be seen by others, by their communities and his work was focused on the long term: more than twenty years between his doctorate fieldwork and the publication of the book. He has a great knowledge of Javanese and Balinese culture, and we can feel his sensitivity in his approach to participants throughout the process, from the field to the representation made in the book.

Véronique Senécal-Lirette has a master's degree in social work from the Université du Québec en Outaouais, with her primariy field research taking place in Senegal. She has worked as a counselor for people who have experienced violence, addiction and mental health issues. Her research interests include women's rights, mental health, traditions and the arts.