Svenja Schöneich, 2023, Living on a Time Bomb: Local Negotiations of Oil Extraction in a Mexican Community, New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 256 pp., ISBN 9781800736566

Like so many other small towns in the northern Veracruz San Andrés oilfield, residents of the predominately indigenous Mexican community of Emiliano Zapata find themselves stuck in a precarious situation given longtime local dependency on subsoil resource extraction. As a result, employment, health, safety, and culture have all been sacrificed on the altar of fossil fuel consumption.

Officially begun as a postrevolutionary ejido in 1936 and proudly named after the one Mexican revolutionary leader whose reputation as a popular advocate is still well honored, the community of Emilio Zapata has been closely associated with oil since the turn of the twentieth century. The 1938 Mexican oil nationalization brought regional industry operations under the control of the state run Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) administration which soon oversaw a successful period of petroleum-led development.

As PEMEX engagement in Emilio Zapata accelerated during mid-1950s, however, few locals knew their rights, and little was done at the time to challenge sprawling industry operations. Soon the production of oil and gas became so interwoven with community life that nearly all social, cultural, and environmental aspects were impacted. Language, labor, lifestyles, ideas, and customs changed. Sadly too, contamination, accidents, and death have visited the town.

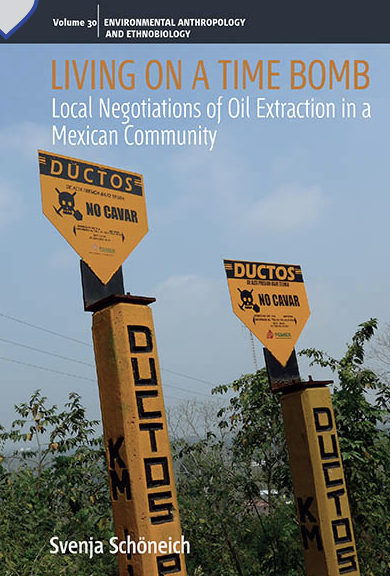

In 1966, ten people perished and eight were severely injured when a series of pipeline explosions (known as the quemazón) burned a neighboring settlement in 1966. Similar industry related mishaps have happened with some frequency since creating unavoidable uncertainty and fear.

Emiliano Zapata was an active PEMEX site for nearly eighty years. During this time industry money contributed to the building of roads, schools, health services and more. Houses were built with durable, modern materials and the community enjoyed greater convenience and improved access to regional urban centers such as Poza Rica, Papantla, Xalapa and the port of Veracruz further to the south. National elites once heaped praise upon the state-owned PEMEX enterprise and characterized it as a harbinger of social progress. Eventually, however, Mexico’s oil industry fell into decline. National energy reform in 2013-2014 largely ended the golden PEMEX years with privatization.

For the people of Emiliano Zapata, oil industry largesse has dried up. Now those who remain reckon only with the ghost of the former heavyweight. Some call it “the Dragon,” conjuring an image of a powerful monster that can all too easily either benefit or burn. Mostly, locals feel the burn as continuing industry operations are noisy and foul smelling. The landscape is littered with abandoned industrial equipment. Local agriculture is compromised and scores of dead fish now float in nearby creeks that once supplied the community with a bounty of edible shrimp.

Just as oil industry development brought prosperity, the current decline has created new imperatives—not all negative so Schöneich claims:

The activities at the extraction wells and the processing plants have decreased during the last decade, less staff is transported to the site and the opportunities for day laboring in the oil industry have also decreased. However, with the fading boom and less extraction activity, the material construction of infrastructure and their inscription in the territory of Emiliano Zapata led to a changing set of circumstances for the community members, which call for new strategies of adaptation and dealing (125).

Put another way, difficult choices exist now that most of the “drilling and redrilling has been done” (128). Those with the skills and motivation to find energy industry work elsewhere can do so. Some more family-oriented individuals send much needed remittances back home. Meantime, a handful of foreign companies have been enlisted to service oil infrastructure in Emiliano Zapata in order to keep extractive operations somewhat afloat. The problem is that necessary follow through has been spotty. Some former local oil workers have noted that “a Venezuelan company…won a thirty-year contract to provide maintenance to industry installations…[b]ut PEMEX hasn’t paid them yet,” (129).

Given over to greenwashing, PEMEX has engaged various social and environmental initiatives aimed at revitalizing the extractive sector. Those in Emiliano Zapata have seen little in the way of new investment, however, forcing residents to make the best of an otherwise bad situation. Some, for example, have taken old pipeline material and used it to remodel their homes. Others scavenge abandoned equipment and repurpose it for fencing, outdoor furniture, and other configurations. Yet despite winning points for clever innovation, these creative ventures seem only to provide post-industrial touches to resident properties. Emiliano Zapata seems to be a place largely left with a series of hollowed out parcels set on a patchwork of ejido land.

Fashionable academic jargon and an overdetermined deployment of social science in text references sometimes clutters Schöneich’s writing.Nevertheless, she paints a vivid picture of an oil town tragedy in the making.Largely a wasteland gutted by incessant fossil fuel extraction and company exploitation, the people of Emiliano Zapata today do seem to be “living on a time bomb” or, at the very least, in a twenty-first century ghost town where seemingly all the young people have left and only a handful of old-timers remain to keep memory alive.

Andrew Grant Wood is the Rutland Professor of History at the University of Tulsa. He was born in Montreal, Canada, and his research focuses on the history of Mexico. Wood has published on a variety of social and cultural topics: urbanization, immigration, grassroots collective action, housing, regional politics, civic ritual and celebration, tourism, film, and popular music. He is author of Agustín Lara: A Cultural Biography (Oxford, 2014) and is editor and contributor to The Business of Leisure: Tourism History in Latin America and the Caribbean (Nebraska U Press, 2021). Wood is currently writing a history of the port of Veracruz, Mexico.

© 2024 Andrew Grant Wood

Download PDF

![]()