KENNETH G. HIRTH, DAVID M. CARBALLO, AND BARBARA ARROYO (EDS.), 2020, Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City. Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Symposia and Colloquia, Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN: 978-

088402-4675. 528 pp.

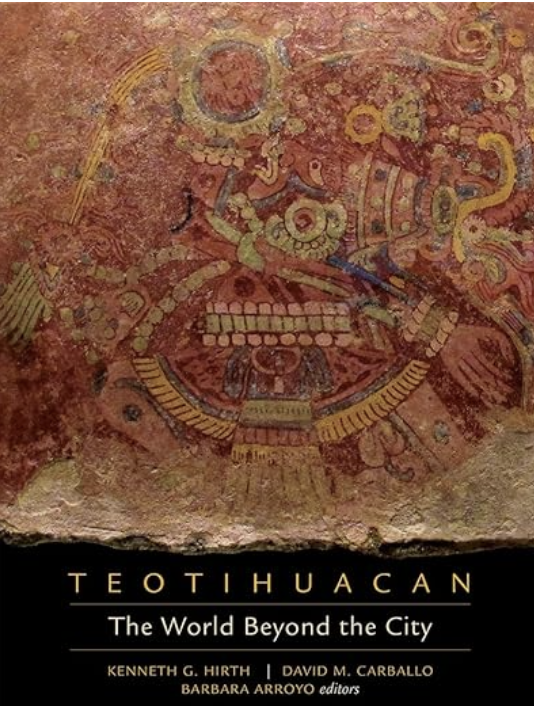

Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City is a scholarly coffee-table size volume of 15 chapters, written by two dozen authors, and is the result of a Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Symposia symposium which brought together specialists in art and archaeology to develop a synthetic overview of the urban, political, economic, and religious organization of a strategic power in Classic-period Mesoamerica. It provides the first comparative discussion of Teotihuacan’s foreign policy with respect to the Central Mexican Highlands, Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Maya Lowlands and Highlands. Contributors discuss whether Teotihuacan’s interactions were hegemonic, diplomatic, stylistic, or a combination of these or other social processes. The authors draw on recent investigations and discoveries to update models of Teotihuacan’s history CE 100-650, in the process covering various questions about the nature of Teotihuacan’s commercial relations, political structure, military relationships with outlying areas, the prestige of the city, and the worldview it espoused through both monumental architecture and portable media.

The volume is organized into an “Introduction” by the three editors (Chapter 1); three Parts: I “The Organization of Teotihuacan Society” (Chapters 2–4); II “Iconography at Teotihuacan and Abroad” (Chapters 5–7); and III “Teotihuacan Outside the City” (Chapters 8–15); “Discussion” (Chapter 16); a list of “Contributors”; and a valuable, detailed “Index.” Each chapter has its own “References Cited” rather than a conflated compilation, so that each chapter stands alone as a publication.

In the initial chapter, the editors discuss the development of Teotihuacan commencing with its cultural influence throughout Mesoamerica and correctly note that that our knowledge of its past has emphasized more about the urban center than its role as a state. The cultural phases, evidence of foreign enclaves, and direct and indirect contact with further distant polities for commerce, pilgrimages, political alliances, and militarism are reviewed.

In Part I, Michael Smith considers Teotihuacan as an international cosmopolitan city with evidence of neighborhoods of foreigners, and a distributor of foreign goods, plus foreign writing and artistic styles. He contends that Teotihuacan was a “world city” like Imperial Rome. David Carballo reviews its political organization beginning in the Late Preclassic, citing models, mechanisms, the evidence for sacred precincts, urban governance, and social inequality polycentric organization within the barrios. Kenneth Hirth examines the internal economy of the city (notably obsidian sources and craft activities) and details Teotihuacan’s long-distance trade as a collaborative, cooperative, and commercial enterprise involving the intermediate elite.

The chapters on iconography include the Nawa Sugiyama et al. assessment of Teotihuacan-Maya Interactions from the Plaza of the Columns Complex in the Teotihuacan ceremonial center, particularly Maya murals with mythological creatures and offerings of high-quality Maya-made ceramics dated AD 300-350. In another chapter, Mathew Robb reviews Gulf Coast evidence, including stela, slate discs, and pyrite mirrors, the latter which became elite mortuary offerings. Diana Magaloni-Kerpel and her associates focus on ceramic vessels and wall murals from elite residential compounds and uses in burials, offerings, and caches. They analyzed pastes, finishes, and pigments (reds and greens) using X-ray, pXRF, PLM, SEM-EDS, and Raman, and SEM-EDS analyses.

In Chapters 7, the late Deb Nichols (1952-2022) characterizes Teotihuacan as a primate city, and its architecture, pottery (imported wares such as Thin Orange and Granular), and craft production, and hinterlands as components of state polity. She assessed the evidence for residential workshops, hydraulic cultivation, transportation corridors, and the corporate commercial model proposed by Hirth with intermediate elites governing neighborhoods. Mexican archaeologists Gabriela Uruñuela y Ladrón de Guevara and Patricia Plunket examine the relationships between the city-state of Cholula and Teotihuacan starting with the Middle Formative period and trade in commodities to illustrate relationships between the two polities. They also examine the chronological growth sequences of Teotihuacan’s Moon Pyramid and the Great Pyramid at Cholula. Agents and political and economic interaction networks between Teotihuacan and the Gulf Coast are documented by Wesley Stoner and Marc Marino. Four divergent networks were characterized using ceramics, iconography, lapidary, and mortuary evidence. Gary Feinman and Linda Nicholas assess Teotihuacan-Oaxaca models of exchange interaction, notably foreign in-migration, social emulation, commercial relations, and political alliances. They also examine Teotihuacan’s external trade expeditions as related to chronologies and calendrics.

Marcello Canuto and Ernesto Arredondo explore binary opposites: foreign conquest versus elite emulation, in Teotihuacan and the Maya Lowlands as seen in stelae and obsidian sources at the El Achiotal ruins in the northwest Peten, Guatemala, and argue that the Lowland Maya were not integrated into the Teotihuacan Empire. Next, Claudia García-Des Lauriers examines cacao, copal incense, jade artifacts, tropical bird feathers, and obsidian as major objects of in the economic interactions between Teotihuacan and the southeastern Pacific Coast of Mesoamerica. The Los Horcones and Montaña sites are proposed as hubs of economic exchange and religious practices. Barbara Arroyo focuses on relationships between Teotihuacan and the Guatemalan sites of Kaminaljuyu, and Escuintla, and the Maya Highlands’ trade and sociopolitical connections. The local Maya adopted Teotihuacan customs in architecture and ceramics, and other parallels include landscape manipulation, water control for cultivation, building and offerings, and multiethnic enclaves. Michael Smith suggests models that enable scholars to better appreciate the significance and implications of the rich data of archaeology, epigraphy, and art history presented in the other chapters of this book. He suggests a three-stage procedure that can help create a better scholarly understanding of Teotihuacan and its role in Classic period Mesoamerica. Lastly, he presents case studies and characterizes the Teotihuacan Empire.

In the final chapter, William Fash provides a detailed, substantive review of the conference papers, and critiques and expands some concepts presented by other contributors. Teotihuacan residents and corporate groups abroad suggest new models of the organization of commerce and revisions to earlier thinking. He elaborates three main topics: 1) The organization of the city and relations with its partners which changed through space and time; 2) The origins and development of Teotihuacan ideology which promoted pilgrimages and commerce; and 3) Economic benefits that came to all parties, provided by the centripetal and centrifugal power of a market economy.

The editors and international contributors to Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City must be congratulated for producing this significant achievement in Mesoamerican archaeology and art history, and have established a benchmark that will likely not be succeeded in some time. The volume is the product of the well-attended Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Symposium in the autumn of 2017 and promptly published thereafter. The editors were the symposium’s organizers and selected scholars who had, and continue to conduct, substantive research at Teotihuacan and in regions of Mesoamerica where the Classic period polity influenced local societies’ economies and religious practices. The chapters present current information and propose a number of paradigms based upon the assembled data. Collectively, the authors have compiled a work upon which future research can and will be based. The volume is a valuable asset to research libraries and an important contribution to regional studies, and should be emulated in other areas of the globe.

Charles C. Kolb, Ph.D., RPA. Independent Scholar. He holds a B.A. in History from the Pennsylvania State University and earned his Ph.D. at Penn State in Anthropology and Archaeology focusing on Latin America and Central Asia. From 1962-2018 he conducted archaeological and ecological field work in Mesoamerica, Central Asia, and Northeastern North America. He taught for 24 years at Penn State, Bryn Mawr, and Mercyhurst University, and retired after 23 years as Senior Program Officer at the National Endowment for the Humanities (USA). Kolb has conducted archaeometric analyses on ceramics since 1962, and served for 26 years as Associate Editor for Archaeological Ceramics with the Bulletin of the Society for Archaeological Sciences. Since 1965 he has authored 6 monographs, 168 articles and book chapters, 856 book reviews (print and internet in 69 different professional publications), and written 63 encyclopedia contributions.

© 2023 Charles C. Kolb