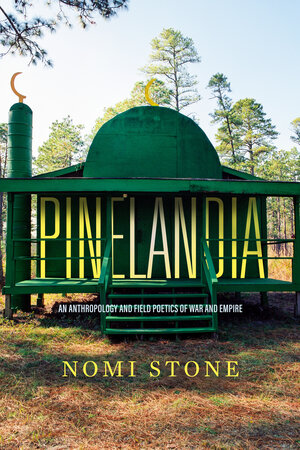

Stone, Nomi. 2022. Pinelandia: An Anthropology and Field Poetics of War and Empire. Oakland: University of California Press, 307pp. ISBN: 9780520975491

Keywords: poetry, militarism, indefinite wars, empire, human technology, Iraqi diaspora

The term “left of bang,” as American anthropologist and poet Nomi Stone opens in her latest work Pinelandia, indicates an imagined space along an artificial spectrum of defensive (read: hegemonic) intervention with “bang” being a zero-point denotating open, oppositional violence to American desires. Situated in this semi-mythical “left” dimension is an American military training program – referred to as a qualification or “Q” course – that takes as one of its many stages the “country” of Pineland. If Pineland has never appeared on your geopolitical radar, that may be due to the fact the United States is the only country recognizing or funding a purposely rogue nation that emerges when needed along the rolling hills and amidst the dense pine forests of North Carolina. The purpose of Pineland, comprised these days of madrasas, mosques, and Middle Eastern markets, is to provide an immersive training space for American special forces to practice persuading “local” Pinelandians (often role-players hired from the Iraqi diaspora for their perceived ability to compliment training verisimilitude) to join forces so as to enact a desired outcome. Success in this qualification course means remaining invisible and left of bang by ultimately achieving a cultural rapport that in turn influences locals to subvert or re-direct Pineland into the realm of American/North Atlantic influence.

It is here that Stone re-engages the ethnographic inquiries and interrogations of affect that informed her stark, widely-praised volume of poetry Kill Class. In so doing, she furthers her efforts to decenter the lived experience of the American soldier in so-called “war literature” so as to discover and discuss the positionality, precarity, and enforced performances of the Iraqi role-players in Pineland. Role-players that come to be seen as sought-after tools in American military efforts to militarize or weaponize culture. Drawing on years of fieldwork that finds her connecting with the concepts of identity, (conflicted) allegiances, and life in the Iraqi diaspora, Stone flows forth from her work in Kill Class to write into reality a theoretical and methodological path that leads to fresh spaces from which to examine war, militaries, human technology, and the mechanics of empire. However, while necessarily including voices and perspectives of American military personal into Pinelandia, Stone is quick to underline that “this book is not proposing [Q courses or Pineland] should be ‘improved’ or made more ‘authentic,’ but rather critiques their core logics as well as the indefinite wars that produce them” (2022, 8).

The connective concept woven by Stone through the chapters of Pinelandia is “human technology;” a trope she argues is an appropriate entry point, despite its dehumanizing tone, as the “military logics and discourse” (2022, 16) inform a certain positionality that cannot be disregarded. This as both the soldiers training within Pineland as well as the Iraqi “locals” paid to perform in the constructed space are seen by the military as tools – with or without their informed consent toward such a role or its ramifications. In a line, Stone offers a poignant encapsulation: “Empire creates the frame here, conscripting individuals as human technology to perform its fantasies, without shielding them from the costs” (2022, 101). Indeed, closely following Stone’s development of fieldwork alongside the Iraqi diaspora employed as actors to recreate (the basest) aspects of Middle Eastern life-worlds is her examination and ultimate estimation that she “felt increasingly uncannily enmeshed in the simulations: just as many Iraqi role-players had been…(l)ike them, I was playing a military version of myself (American woman, outsider), but not on my own terms” (2022, 192). Here, Stone’s command of the Arabic language as well as extensive participant observation and insightful discussions (at times far from her fieldwork in the fictionalized fragment of North Carolina soil) contribute careful and curated substrates of experience, evidence, and evocation that build into her overall argumentation and theoretical engagements. While moving through these associated geographies of empire and variations of the anthropological “field” in Pinelandia, we can sense the traditional signs of multi-sited fieldwork. Yet Stone’s efforts may perhaps be viewed more engagingly through the lens of a “single geographically discontinuous site,” a conceptualization Ghassan Hage (2005) arranges and argues for during his own transnational research. As such, we are guided to gauge and reimagine the structure of fieldwork not only within or at a distance from “empire,” but also to evaluate and expand upon alternate ethnographic encounters that can contribute to the anthropology of “long wars,” militarism, and (imperial) power.

Though a close, cover-to-cover examination of Pinelandia allows the strengthening of certain lines – narrative and argumentation, methodological and reflexive positionality – in a reader’s mind, the book is also relatively accessible on a chapter-to-chapter basis with key themes reiterated and critical actors surrounded by contextualization. In turn, Stone seeks a trenchant examination of counter-insurgency (COIN) strategies thus also of the key COIN texts that have steadily emerged since the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Furthering this pursuit, she highlights interviews and encounters with a broad spectrum of actors; from the lofty heights of military hierarchy overseeing training strategies to the individual soldiers seeking to successfully complete the Q course. From further behind the scenes, Stone brings into focus the anthro-mercs (anthropologist + mercenary) picking at the remains of the U.S. military’s Human Terrain Project and the private military contractors providing a wide array of products – people, pigs, or pre-fab imaginations – to Pineland. Along the way, we are directed into a selection of perils and pitfalls shaping participant observation and fieldwork that, at times, can far outpace notions of control or consent. Alternately, academically-oriented readers will also find repeated theoretical positioning and interpretation via the work of Deleuze and Guattari as well as sustained meditations on Martin Heidegger’s conceptualization of the (working) tool. Readers from a military background will encounter a mirror that, far from flattering, will offer a patient practitioner of war games and cultural training strategies a new reflection from which to realize and rethink. While Stone repeatedly (and persuasively) returns to the impossibility of what such training and strategies seek to accomplish, a military affiliated reader may come away with an entirely different set of conclusions: “lessons learned” to be added to a playbook assembled to deflect us from seeing the impossibility of the desired military praxis and performance (a deflection especially desired, as Stone notes, when there are congress(wo)men courting voters and military contractors courting Congress).

A final structuring/generative component of Stone’s Pinelandia must be highlighted: poetry. In the book’s epilogue, Stone assembles a micro-masterclass in “using poetry to build anthropological worlds” (2022, 209) that is accompanied by a robust bibliography of (emerging) poetic practice and possibility. It is a defining epilogue that will speak on multiple levels to established academics, multi-modal ethnographers, and emerging anthropologists seeking to shape (or more rigorously reinforce) the role of poetry both in the generation of knowledge as well as in the expression of ethno-encounters. Strategically placed within the volume by Stone, the reader encounters the epilogue’s incisive insights after first engaging with her “Field Poems” and “Field Poem Fragment(s)” that, more than excerpts allowing mere contextualization or ethnographic texture, seek to actively collaborate in the generation of the overall text. This reflects a desire for the poem fragments to engage the reader directly while further subsensory explanations and thoughts intersecting with her poetry are held until after the book’s conclusion. In a sense then, Stone’s poetry and (self)reflexivity vis-a-vis the role of poetry in anthropology is but one reply to a question posed and pierced by Sapiens poetry editor, Christine Weeber, and inaugural Sapiens poet-in-residence, Justin D. Wright, in their 2022 essay, “What Is Anthropological Poetry?” Their key theme of poetry-as-transformation in “thinking and being” connects with Stone’s own personal transformations during her extensive participant observation in Pineland as well as across the diasporic plane (re)generated by her research reciprocators. This while also engaging a transformative conversation that chips away military perceptions of weaponized culture, rapport-via-research-and-regurgitation, the contradictory coercions imperialism seeks from “the local,” and the fallacy of finding positions “left of bang” when you are the bang. A conversation that is considered here, in the style of Stone, with a brief, concluding assemblage elicited by a reading of Pinelandia:

We may be

free to find

an insurgent line,

that ties or lies or plies

a truth to time…

yet the iamb of our land(ia)

meters a might,

that wants to be “right” (of bang)…

Thusly, (s)killed being the left -behind

being the righteous -aligned

is the riposte & reciprocity scaling

our economy of allegiance & identity,

as poetic proximities find or define

(en)forced futures of fictional lands.

Bibliography

Hage, Ghassan. 2005. “A not so multi-sited ethnography of a not so imagined community.” Anthropological Theory 5(4): 463-475.

Weeber, Christine, and Justin D. Wright. “What Is Anthropological Poetry?” Sapiens (30 August 2022). Accessed September 2022. https:// https://www.sapiens.org/culture/what-is-anthropological-poetry/.

Charles O. Warner III is a doctoral researcher with the Faculty of Social & Cultural Anthropology and Leuven International & European Studies (LINES) at the University of Leuven, Belgium. He holds a fundamental research grant from the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) with research emphases on veterans studies and strategic peacebuilding in former Yugoslavia. Prior to his turn to academia, Charles served as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) technician in the U.S. Air Force for six years, conducting counter-terrorism, counter-insurgency, and force protection missions in South Korea, Iraq, Germany, and the United States.

© 2023 Charles O. Warner III

![]()