M. Taussig, 2020, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 220 pp, ISBN 978-0-226-69867-0

Keywords: Michael Taussig; meltdown; metamorphic sublime; mimesis; mastery of non-mastery

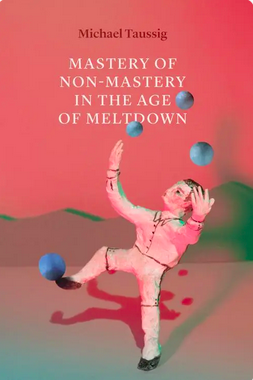

In his most recent book, Mastery of Non-Mastery in the Age of Meltdown, Michael Taussig, with his ingenuity and wit, presents a chronicle of contemporaneity. The main argument of the book is hinted at on its cover. Illustrated by Olivia Taussig, the cover invokes the general theme of Taussig’s analysis: a boy (and his shadow) tries to balance the balls (or are they planets?) which he juggles, probably in order to avoid the collapse invoked in the title of the book. Just like the balls in the illustration, our planet is in serious danger of collapsing, victim of a toxic economic system, fascist politics, and the destruction of the environment.

In the nineteen chapters that make up the book, Taussig reflects on a world on the brink of collapse; a world which is based on a “new normal” marked by the “fantastic power of catastrophe” and the non-existence of the ordinary. Thus, the author reflects on the recent world context characterized by Donald Trump (whom Taussig calls ironically “Shaman-in-Chief”), natural disasters, the Green New Deal, Facebook, Twitter, and the state of technological surveillance. The description of this context is intertwined with dense theoretical analyses. The result of his narrative seems to have the goal of creating what Taussig names, right at the beginning of the text, the “smoke and mirrors game,” in which the mirror represents the mimetic element, and the smoke the mystery. When the smoke is mixed with reflections on the mirror, a “metamorphic sublime,” as he calls it, is created.

For readers already familiarized with his work, the return to issues present in previous books will be noticeable, though reread from the concept that guides the book: the idea of mastery of non-mastery (MNM). In general terms, mastery of non-mastery refers to the organization of mimesis as the basis of domination, based on a mimetic excess (“mimicry miming itself”), in which there is a re-enchantment of nature, which has the peculiarity of being more surreal each time. This “dark surrealism” will be the mark of the “new normal,” characterized by strangeness and a reactive nature. In this re-enchantment of the world, the tropes of demystification and enlightenment give way to what he calls Art vs Art, based on “new possibilities of thought and politics, rhetoric and power” (p. 144). The idea is no longer about thinking about ideology vs truth or discourse vs counter-discourse, but Art vs Art, a paradigm that follows the metamorphic sublime and is based on “camouflage, montage, collage, ventriloquism and tweetery.” Thus, by proposing the notion of mastery of non-mastery, Taussig invites us to think about mutuality with nature, instead of colonization and exploitation of the natural world by man. Mastery of non-mastery therefore refers to the disorganization of the organization of mimesis (p. 16), a kind of counter-magic that unrolls layers of paradoxes.

Another striking feature of Taussig’s broader work reappears in Mastery of Non-Mastery in the Age of Meltdown: the powerful and ironic writing that challenges the framing of specific genres and that questions anthropological language itself, expanding its meaning. The author even points to the fictional character of ethnography by evoking Malinowski (whom he calls a performer). Taussig considers the persuasive way in which Malinowski convinces us, through writing and photographs (that is, mimicking), that he was alone among the Trobriands, creating the “illusion of authorial presence.” Taussig takes these reflections further by stating that mastery of non-mastery (MNM) of writing, the central proposal of the book, is a cross between writing and theater, occupying a space between “science fiction, high theory and weather.” Above all, it can be said that the book provides a form of writing that questions itself and the capacity for representation, especially in a context of catastrophe, which escapes simple descriptions. The meltdown is seen as a force that pushes us to think in a new language – that of transgression, above all – and in new forms of “response, evocation, and being” (p. 30), in which nature is seen and felt from an entirely new way.

Taussig maintains another of his characteristics in the book: the dense and meticulous reflection of philosophical and anthropological concepts, intertwined with references from literature, cinema, television, and politics. In the book, there are references to Nietzsche, Roland Barthes, Aby Warburg, Georges Bataille and the Sacred Sociology, Simone Weil, and Michel Foucault, usual theorists in Taussig’s reflections. In this sense, it is worth highlighting the reinterpretation he makes of Walter Benjamin’s thought, though similar efforts appear in his other books, such as Walter Benjamin ’s Grave (2006) or Palma Africana (2018). His thoughts on the mimetic faculty, understood as the way in which nature creates similarities, something remarkable among children, but which has been forgotten by Western science, is inspired by Benjamin’s thinking, specifically the essays “Doctrine of the similar” and “On the mimetic faculty.” Taussig proposes to take the concept of mimetic further, demonstrating how the current moment, encapsulated in the idea of the metamorphic sublime, is characterized by mirroring and mimetic excess.

Something striking while reading the book is the evocation, in different moments and contexts, of the figure of the sun. Taussig even questions the extent to which our lives are connected to the sun and the rhythm of death and resurrection that its movement of rising and setting generates. In this way, all of us, through our bodily unconscious, are oriented towards the sun without even being aware of it. It is the sun, through the illusion of a vertical movement – which is actually the rotation of the Earth – that gives guidance to our daily self. This bodily unconscious knowledge is what makes our body, the body of the other, and the body of the world gain meaning.

The future seems to be murky; it cannot be described as dawn or twilight, but as something strange for which we have only just begun to build a representational language. The meltdown, which results largely from climate change and fascist politics, heightens our awareness of the body as well as the cosmos, something that becomes palpable when Taussig describes hurricanes that hit New York and the Bahamas, for example. How to describe the terror, the nightmare, the catastrophe, the unbelievable? How to move past “representational inertia” (p. 32)? Taussig seeks the answer to this question by evoking Bataille, who uses the sun as a central figure in his writings, and reflections by Foucault about Bataille, especially with a focus on transgression. Thus, Taussig claims a “negation of negation” would be necessary, in which transgression starts to be considered a liberating language. He proposes that we think of catastrophe and the environmental and political meltdown as phenomena permeated by a sacred and mythical force. It is exactly there, in this empty representational space, that the mastery of non-mastery appears, as a basis and hope in a world marked by fear and fascism. Taussig proposes to use terror against itself, the re-enchantment through an art that evokes life, the adoption of a shamanic curiosity about the natural world that thinks in “multiple realities” and in a life based on perspective and error and, finally, the search for an engagement with the body and with the body in the world. In this sense. Taussig’s book helps one consider new paths for understanding our contemporary world and the various forms of violence, dominance and destruction that haunt us. In a way, it is a call to act and to create a world of mutuality.

References:

Taussig, Michael. Walter Benjamin’s Grave. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2006.

Taussig, Michael. Palma Africana. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2018.

Carolina Parreiras is an anthropologist and postdoctoral researcher at the State University of Campinas, Brazil. She was a Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Latin American Studies (ILAS) at Columbia University (2019 -2020). The main goal of her current research is to understand the forms of classification and nomination of public and private forms of violence in favelas, with a focus on the use of digital platforms and environments, digital violence and digital inequalities. carolparreiras@gmail.com

© 2021 Carolina Parreiras