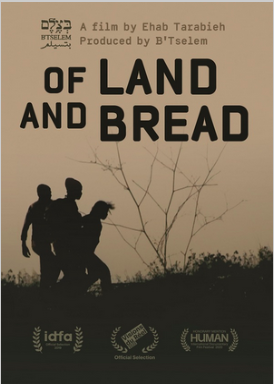

Produced by B’Tselem and Ehab Tarabieh. 2019. The Video Project.

“When everyone on earth dies, the last person should play this while walking into the sunset” writes a Youtuber, in a very dramatic tone, about Handel’s Sarabanda,1 which constitutes the sole soundtrack of the documentary Of Land and Bread, repeated over and over. I watched it in two evenings while on a solitary retreat and it put me on the verge of tears. Of Land and Bread can be emotionally experienced as walking into the last sunset of humanitarianism with a feeling of impotence and sadness that in my case didn’t turn into outrage. If compassion is one of the emotions aroused by the documentary, then it can develop into empathy and taking action to stop the naked oppression portrayed by the documentary of Palestinians in the occupied territories and West Bank. Perhaps that is the purpose of documenting the everyday experience of Israeli occupation through the “naked eye” of the video camera. The documentary does not provide any background, contextualization, or explanation. We only learn that B’Tselem (an Israeli human rights organization) began its Camera Project in 2006 by distributing cameras to Palestinian volunteers (the video makers) and that the Project lasted 10 years.

The documentary is neither neutral, objective as far as objectivity can go, nor inclusive. It consists of video fragments (stories, or pieces of visual story telling) pinned together and showing a Palestinian perspective on the occupation and the Israelis. These are represented by soldiers and the (illegal) settlers. What the documentary depicts is oppression seen by the oppressed in a land that is supposed to be or have been the land of the people today known as Palestinians, which is what the Israeli settlers, backed by the army, deny. The opening scene (without title) shows an Israeli settler approaching a group of Palestinians planting a field. He asks them to share their piece of land with him:

—I’ll plant half and you [will plant] the other half … we need to eat.

—Why? —they ask —This land is ours.

—This land is part of Israel … it belongs to the Jews … God gave it to us [Leviticus].

—But this is my father’s land.

—When the Messiah arrives, you will be our slaves … we’ll treat you well if you behave… You have Syria, Arabia … you have land … —

The settler knows he’s being filmed but keeps going until Israeli soldiers appear, though not to stop him. Their role is shown in the following stories.

A similar argument informs the story called “The Flag.” There seems to be a gathering of settlers, a celebration filmed from a Palestinian house. The settlers see a Palestinian flag on the roof of that house and one of them climbs to the roof but gets stuck in barbed wires.

A dialogue follows between the Palestinian, owner of the house, and the settler, who wants to take down what he calls a “Jordanian flag”:

—Take down the Jordanian flag … this land is all mine … God gave [it] to the Jews … It’s only the Jewish people who lived in this land from the very beginning.

The house is private property. Israeli soldiers arrive to the roof entering through the door, not to arrest the intruder but the owner of the house: “take the flag down, or we’re going to arrest you.” In the end, they just leave the house.

The harassment and discrimination that Palestinians suffer in the street is part of everyday life. A soldier, captured by the lens, shouts (in the story called “Carnival”), “you can’t stay here … this place is for Jews! In “Taking the High Road” a soldier warns a Palestinian: “you can’t go this way; this is only for Jews.” Palestinians must walk along a different section of the street, one designated only for them. “These are our orders,” says the soldier. The “we just follow orders” rings a bell, and not a nice one.

STONES AS GUNS

Most of the stories are about children and stones. A soldier grabs a child who seemingly has thrown a stone at an army car. The child cries hard thinking he is going to be arrested. His father arrives and is detained and blindfolded. In the end both are released. Then there are the night home visits. Soldiers enter in the middle of the night, waking up the whole family and children who are sleeping, asking for identification, taking pictures, asking children if they throw stones, and then leaving. A father asks, “why don’t you come during daytime?” (“A Bedtime Story”).

It is a different story when settlers throw stones. We see a whole crowd of settlers harassing a Palestinian house (or maybe an apartment), hurling stones and insults of a religious, sexual and gendered nature using loudspeakers and playing loud music all night long (included in the 90 minutes version of the film). Soldiers stand nearby but don’t move a finger. “They are our soldiers!” a settler says.

When soldiers don’t know that they are filmed they perform nastier actions. In one of the stories, a soldier kicks a child who is on the ground pinned down by another soldier. In another story, a young Palestinian hides in a store room, unarmed. Soldiers find him and beat him senseless for around five minutes, real time. One of the soldiers nails him repeatedly on the side with the barrel of his gun, as if it was a spear.

NOT EVEN IN DEATH IS THERE A BREAK

Heartbreaking is “The Old Man Funeral”: A water cannon pushes back a small funeral procession of a handful of men escorting a coffin. There’s not even noticeable rage as they turn back, heads down.

The stories document, one after another, oppression and powerlessness without comments, without context. They are not the “whole truth,” not the “whole story,” but what we see, as if we were eyewitnesses, is something that has happened, and keeps happening in the West Bank and occupied territories. But the documentary has been produced by the Israeli NGO B’Tselem, which is concerned with human rights violations. In the Israeli society, there are people who are aware of what is going on in the West Bank and are working, as the objective statement of B’Tselem states, “to end this regime, as that is the only way forward to a future in which human rights, democracy, liberty and equality are ensured to all people, both Palestinian and Israeli, living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.”2 It seems then that one goal of the documentary is to make the world aware of what is happening, to move people and organizations to say something, to do something. Publicity of oppression is one way to fight against it.

The social world, however, is presented in a messy way, as it is. It must be organized through contextualization and analysis. This is not what textbooks do: they give students an ordered world, neatly structured with typologies and summaries, and without emotions involved. Nothing should be taken at face value. The fact that there is no contextualization can be used as an advantage: students can make sense of what they see in an active and participatory way by working with resources provided by teachers or professors.

The contextualization involves dramatic and conflictive emotions as it includes the history of the arrival of the first Jewish settlers at the end of the 1800 and the reasons why Jews wanted to leave Eastern Europe, because of pogroms and later the Holocaust, and find a haven: their own national Jewish state. But the land was populated by others, as it was in biblical times, and making room for the newcomers in the end meant the displacement of those living on the land: Palestinians. The national identity of the latter is linked to the conflict over the land and the stubborn refusal of Israel to share it (one multiethnic state), precisely what B’Tselem aims at.

It is, therefore, a video that can be used in history, sociology, or anthropology courses dealing with the conflict over the territory in Palestine-Israel, or just conflict, oppression, or powerlessness. On the other hand, the focus can be on the anthropology or sociology of emotions, or even the use of sources. On the emotional side, the most relevant skill to develop, particularly for students of anthropology but also for history students, is empathy: to try and see and feel from the point of view of others, even settlers and soldiers, with the aim of learning to know oneself by learning to know the other, and the other way around. Other emotions to deal with, and be aware of, could be impotence, rage, sadness, outrage, compassion.

The video comes in three formats: 30, 60 and 90 minutes. I prefer the longer version as it contains stories that I find very relevant but were cut in the shorter versions. However, the longer version might be too repetitive and heavy to watch considering that is difficult to keep the interest of students, when there is not a clear story line. I showed the 60 minutes version in a two-hour anthropology class (first year humanities) and after 30 minutes students started to go missing. Depending on the type of group (secondary or third level education; younger or older), it might be better to use only a few of the stories and then work with them. However, if the audience targeted is a group of activists, the 60 minutes version can go very well. Potentially there are two different types of uses: for activism and for learning to work with anthropological/historical thinking concepts and with emotions associated to these concepts. How both types are linked, however, is a different question.

Francisco M. Arqueros is an anthropologist working out of the Department of Geography, History, and Humanities at the University of Almeria, Spain.

© 2021 Francisco M. Arqueros