About Us

The Anthropology Book Forum publishes a broad range of conversations focused on discussing and evaluating newly published work relevant to anthropological audiences, broadly conceived.

We publish online every Monday.

The Anthropology Book Forum will be at the AAAs this year in New Orleans

Come check out our roundtable!

Specters of Academia: Demystifying the Book Publishing Process

This roundtable brings together editors from leading anthropology presses to offer insights into the monograph publishing process. Designed for early-career researchers, the session will offer guidance on the steps involved in transforming a dissertation into a publishable book, from crafting compelling book proposals, preparing manuscripts for submission, to understanding the peer review and revision process. Participants will also discuss emerging trends in academic publishing, such as open access, digital dissemination, interdisciplinary collaboration, and publicity. By engaging directly with publishers, attendees will gain practical advice and a deeper understanding of the expectations, challenges, and opportunities in publishing their book-length work. This roundtable aims to create a supportive environment to ask questions and engage directly with publishers to increase transparency around book publishing. Engaging with the conference theme of ghosts, this roundtable will explore how the book publishing world operates as a specter of academia that shapes intellectual landscapes and career trajectories yet can remain elusive and daunting. Join panelists from Duke University Press, Rutgers, Colorado University Press, Stanford University Press, University of Arizona Press, and University of Chicago Press for their insights and advice on navigating the academic publishing world.

Date and Location:

American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting

New Orleans, LA (United States)

Thursday, November 20th, 2:30 – 4:00 PM.

Sheraton Hotel, Grand Ballroom E (5th fl).

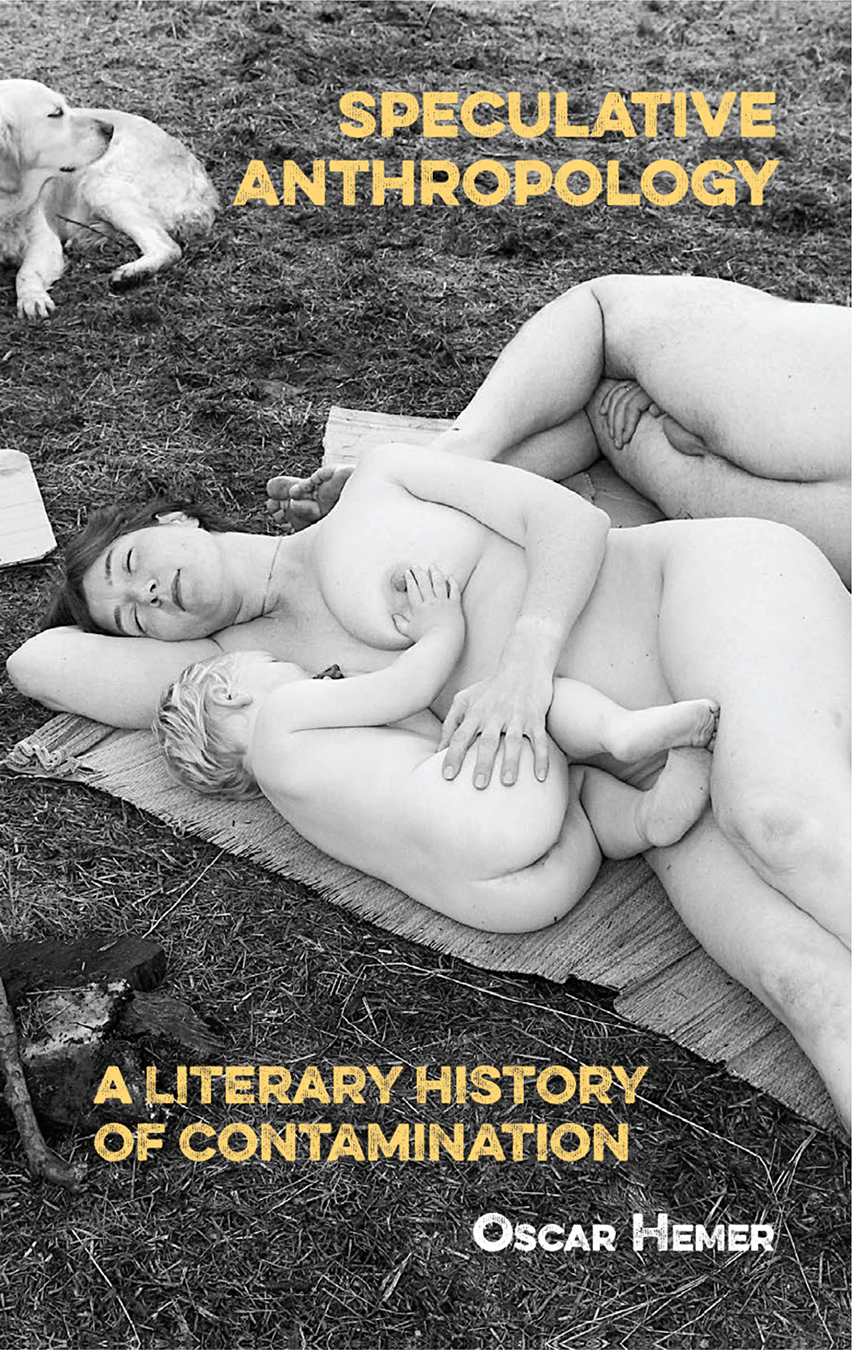

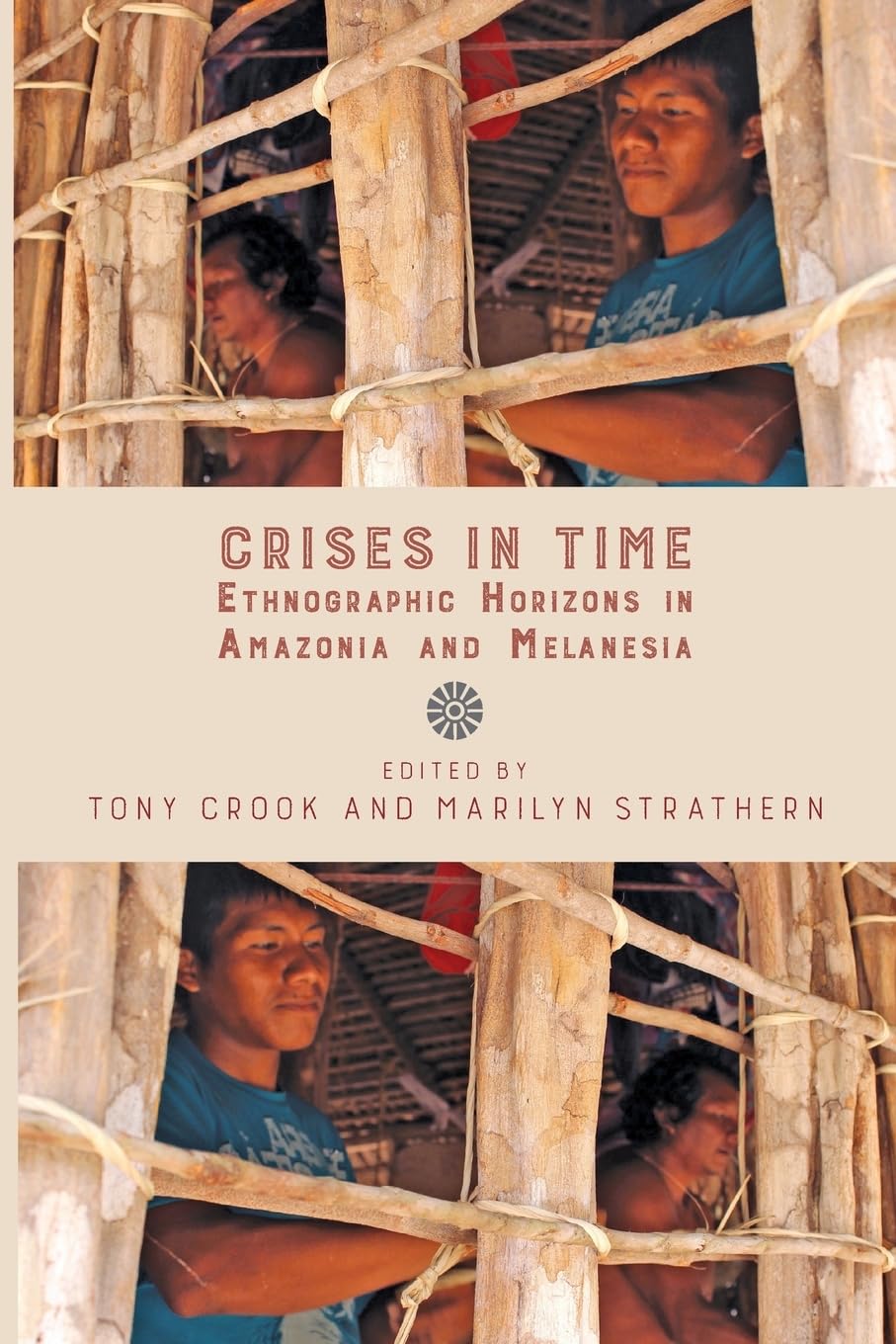

Monthly Featured Books

We work with over 100 publishers around the world to connect readers and authors.

News and Updates

Award winning journal

The Anthropology Book Forum was awarded the 2022 GAD New Directions Award (Group Category) which calls attention to the myriad ways anthropologists are expanding anthropological perspectives in the twenty-first century.

Addition of the Anthropology Review Database

This summer we will begin merging the Anthropology Book Forum with the Anthropology Review Database, a previous journal that published over 3,000 reviews of books, software and films relevant to anthropological audiences.

We hope to be finished by early 2025.

Other-than-English titles

We are looking for reviewers to review books in languages other than English. If you have a book in mind, or are interested in providing a review in a language other than English, please get in touch!

The Anthropology Book Forum is an Open Access publication.

Open Access, as defined in the Berlin Declaration, means unrestricted, online access to peer-reviewed, scholarly research papers and articles for reading and productive re-use, not impeded by any financial, organizational, legal or technical barriers.

The Anthropology Book Forum ascribes to the principles set forth by the Fair Open Access Alliance