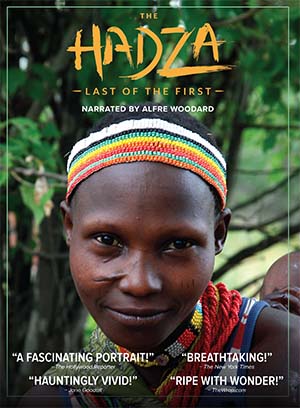

Bill Benenson (director), 2014, The Hadza: The Last Of The First, Benenson Productions and Firestick Productions.

This is a fascinating, watchable documentary on the Hadza people of Tanzania. Anyone interested in hunter-gatherers and their lives in today’s world, as well as their contribution to our understanding of human evolution, will want to see it.

Several headline-grabbing statements justify the title of ‘Last of the First’. But there are important ways in which that designation is true. Of around 1000 Hadza speakers, some 2-300 still live a bush-life as the only equatorial big-game African savannah hunters in the Rift Valley. This places them right in the environment in which our modern human ancestors emerged in the past 200,000 years. There are real aspects of cultural continuity which can teach us about that ancestry, besides a genetic diversity among the Hadza population showing that their lineages are ancient, comparable to those of Khoisan people in southern Africa and Central African forest hunter groups.

The Hadza are known as immediate-return hunter-gatherers, a term developed by the major researcher James Woodburn who has worked with them for over 60 years and speaks their click language Hadzane. This means they keep nothing but consume all they produce on that day; no one can control anyone else’s access to resources; everything is shared, and they are strikingly egalitarian. No single Hadza can tell any other man, woman or child what to do and expect to be obeyed.

Sounds like a beautiful life, and it is. We join the men in the excitement of the chase, aiming their poisoned arrows through the green acacia bush at antelopes, giraffes, zebras, warthogs – everything but elephants, which are not stopped by the poison. We see them sticking their arms into African killer bee nests to get the honey, thanks to the help of the honeyguide bird, who gets some wax. This is fun, much more fun than the hard work of farming, which yields a less healthy diet. That could explain why the Hadza have been so reluctant, despite all the pressures from previous colonial states and the current Tanzanian state, to settle down, usually with disastrous results.

While bow-and-poisoned arrow technology may only be some 50,000 years old, evolutionary anthropologist Richard Wrangham gets down and dirty with the Hadza women digging up roots, using their tsipale digging sticks. These could be 2 million years old in human evolutionary terms. Wrangham has an axe to grind on fire and how cooking made us human, which is a reasonable theory, but fire at that date is a matter of debate among archaeologists. Perhaps half a million years for controlled domestic use would be closer to the mark. Still, he gamely deploys bush Swahili to inveigle himself into the women’s group, before realizing the wily multilingual Hadza women are well able to pick up his English when it suits them.

Gatherer-hunter more fairly reflects the fact that women provide staple food day in, day out, while the men may get lucky and kill once a moon. There are always roots to dig, and in the right season nutritious baobab fruit to knock down from the trees, grind and mix with that rich honey. Alyssa Crittenden, a key researcher on Hadza diet and child-rearing, chats with the famous hard-working Hadza grandmothers who have given us so much insight into the evolution of menopause as a characteristic which made us human: the Grandmother Hypothesis.

Jane Goodall makes a somewhat gratuitous appearance, celebrated as she is for research on nonhuman primates, not the Hadza at all. With all the discrimination they have faced as ‘primitives’, we need to be careful to focus on the Hadza as fully modern, cultural human beings and not in any simple way continuous with two million years of hominin or primate evolution. What made us human is not only use of fire, and foraging technologies, nor even language, but singing, dancing, music, body decoration, rock art, ritual. Although little is said, the film keeps revealing the exuberant culture of the women as they sing energetically. Regarding Hadza ritual and religion, the film can’t show us anything because it all happens in total darkness (no fires) on nights of dark moon beneath the Milky Way.

One of the great Hadza cultural experts and storytellers, Gudo Baala, shows off some local rock art. He reasonably argues that this was made by Hadza ancestors, even though no one is painting today. Since the Hadza hills are full of undocumented rock art, we need to hear these interpretations from the Hadza themselves, just as Khoisan peoples have given insight into Southern African rock art sites.

Gudo lives in the Mang’ola area which in recent decades has been flooded by people from all over Tanzania, seeking their fortune by farming onions under irrigation schemes. This has catastrophic effects on the Hadza environment, water table and bush ecology, driving away the game animals on which they depend. Mang’ola people have been reduced to living on tourist handouts, succumbing to alcoholism.

A great supporter of Hadza cultural conservation through the Dorobo Foundation, Daudi Peterson explains here how the Hadza reject the use of storage, leading to wealth and accumulation. This is the way of life that made us human, for the vast majority of our history, but not the way of life favored by states seeking tax revenues. Even recently, the Tanzanian state almost destroyed Hadza culture at a stroke by offering the whole of Yaeda Valley to the Abu Dhabi royal family as a hunting ground. Thankfully, a Washington Post journalist was able to raise the alarm, and advice was sought from the UN indigenous rights section. A very small – but significant – area of the ancestral Hadza territory has been secured under Hadza governance in the Swahili village system. But it is still tough to enforce anti-poaching and controls on cattle movement.

Especially poignant scenes show Datoga cattle being brought down to waterholes where they monopolize resources needed by the Hadza themselves and the game animals. As Peterson says, these are historic processes being acted out in front of our eyes.

Also very affecting are the various, bewildered reactions of Hadza children reflecting on their experiences in Swahili schools. A couple of lads, who received beatings when they were trying to learn to write, decided they preferred Bush school. They had no problem finding their way home two days walk back across the country. As has been seen with so many other First Nation cultures, Hadza interaction with Tanzanian education is going to be critical in determining how well Hadza culture will be sustained for the future. Tanzanian officials and academics interviewed here show glimmerings of sympathy and awareness of their responsibility in supporting this most ancient culture, a culture which achieves equality and sustainability for all its members every day. Rather than develop the Hadza, aren’t we are the ones needing to learn lessons from them?

Some contribution by the man who knows most about the Hadza, James Woodburn, would have made this an even more excellent film. But the real stars are the Hadza themselves.

Camilla Power is Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at University of East London. She has done field research with the Hadza on women's ritual culture.