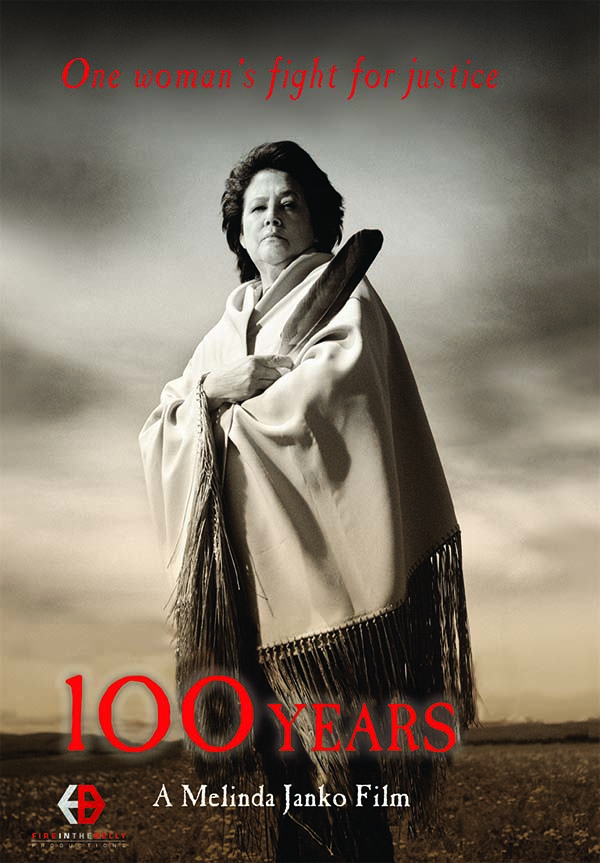

Melinda Janko, 2016, 100 Years: One Woman’s Fight for Justice. The Video Project.

On June 10, 1996, Eloise Cobell did what very few people had attempted or imagined: she sued two agencies of the United States federal government (the Department of the Interior and the Department of the Treasury) for the mismanagement of Indian trust funds and for the prolonged cheating of hundreds of thousands of Native Americans out of billions of dollars. The plaintiff’s purpose was to restore justice and to compel the federal government to fix the broken system that had been dysfunctional for quite a while. To be precise, some eighty years prior, the Joint Commission of the U.S. Congress looked into the accounting methods used by the Administration of the Office of Indian Affairs and found that they were prone to “fraud, corruption, and institutional incompetence almost beyond the possibility of comprehension” (Historical Timeline). The facts of the case, that is, mismanagement of funds by the federal government, were never disputed. Still, it took fifteen years and three presidential administrations for Elouise Cobell and her legal team to finally prevail in the largest class action suit and win a settlement of $3.4 billion.

Melinda Janko’s film “100 Years: One Woman’ Fight for Justice” narrates a complicated path toward that victory. It relates major legal battles and important turning points of the case – lost and intentionally destroyed financial records, incompliance with court orders leading to the contempt trial of high profile officials, the removal of Judge Royce Lamberth (initially assigned to the case) by the U.S. Court of Appeals for abuse of discretion in calling out racism in the federal government, etc. (Garvey 2010:5). By triangulating the perspectives from many parties involved – legal experts, accountants, defendants, and, central to the film, Navajo and Blackfeet Indians on whose land oil companies set up oil wells – the film creates a rich, multi-vocal narrative. It is abject poverty of the Native American communities who reside on the lands holding the world’s richest oil and gas repositories yet who receive pennies in compensation for land use that strikes a nerve with the viewer. The apparently inadequate compensation and insufficient reporting on individual accounts caught the eye of Elouise Cobell, who was Treasurer of her tribe. When her inquiries about Individual Indian Money (as those accounts are designated on the books) only produced repeated dismissals or led to advice to write yet another letter, she decided it was time to “draw a line in the sand.” For the decade that it took to settle the case, Elouise Cobell never lost sight of the opponent she was taking on – the U.S. government – and always remembered that close to a quarter of her tribe once starved to death at the hands of that very same opponent. But the camera captures not only her determination and relentlessness but also her tears as she relates years of fruitless efforts to bring some relief to her community.

Narrating the story behind Cobell v. Salazar, the film taps into a larger context of the federal government’s relationship with Native Americans. It provides some background information regarding the federal policies that shaped the government’s involvement with indigenous peoples, stretching back to the nineteenth-century policy of assimilation and the decision to divide tribal lands, which resulted in assigning allotments to the heads of households but placing those allotments into the government’s trust for 25 years. The crafters of the allotment system strongly believed in private property and its power to instill “the habits of thrift, industry, and individualism, thought to be needed for assimilation into white culture” (Carlson 1981:129). Yet after decades of forced effort, Native Americans “had neither prospered as farmers nor retained ownership of their allotted lands” (130). Since they did not turn into the farmers which the federal government envisioned them to become, the management of Indian lands (and Indian money) by the federal government became a permanent arrangement.

When the settlement in Cobell v. Salazar was reached, the case contained some 3600 documents and over twenty federal court decisions. Not to be lost in this veritable sea of documents, the film follows the logic of the plaintiff’s original claim for accurate accounting of Indian money and never questions the continuity of flawed accounting practices beyond the given case or raises a concern about the continuity of the federal government in its capacity as trustee of Indian assets (as the plaintiffs did not do either). While the film starts with Elouise Cobell talking about patronizing attitudes towards Indians, it eventually offers a quite conventional story of an ordinary, albeit brave, person standing up to the system, a narrative that generally affirms the all too familiar ideological framework according to which American government works and self-corrects in the court of law.

However, a careful listener will notice another, stronger and more impactful, storyline surfacing at various points in the film, namely, the persistent paternalism by the U.S. government towards Native Americans, systemic injustice, and institutional racism. Such framing of the events was publicly voiced by Judge Royce Lamberth who summarized the facts of the case as disgracefully racist and imperialist on the part of the United States government. While Lamberth appears on camera contemplating about his removal from the case, the film leaves out an important piece of the puzzle: Judge Lamberth called out what he believed to be continuous racist and Anglo-centrist practices in the Department of the Interior. Additionally, highlighting the inferior treatment of Native Americans by the federal government, Larry Echo Hawk (one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs) draws attention to Enron’s case which was quickly decided upon since congressmen saw that stealing from primarily white shareholders constitutes an emergency. Yet, a similar case of theft from Native American communities and injustice on an unprecedented scale has not disturbed the country, did not bring people to arms or cause ‘riots on the streets,’ least of all did it urge a speedy remedial action by the government.

Thus, as the film ends, we are left with an uneasy feeling that while Elouise Cobell won the case and checks were mailed out to individual account holders, the governing practices might not have radically changed in the aftermath of her victory and that colonial attitudes towards various ethnic groups may not have been affected at all, and are thus still keeping the empire afloat.

Works Cited:

“Historical Timeline of Indian Trust Funds Management.” (n.a)(n.d.). 100 Years: One Woman’s Fight for Justice. http://www.100yearsthemovies.com/fact-sheet

Carlson, Leonard A. “Land allotment and the decline of American Indian farming.” Explorations in Economic History 18.2 (1981): 128 – 154.

Garvey, Todd. “The Indian Trust Fund Litigation: An Overview of Cobell v. Salazar. Congressional Research Service (2010), RL34628.

© 2019 Natalia Kovalyova

Natalia Kovalyova (Ph.D., UT Austin) studies the relationships between discourse and power in a variety of contexts from presidential communication to academic writing. Her most recent research focuses on the role of the media in producing, maintaining, mending, or challenging social cohesion.