Author Interview

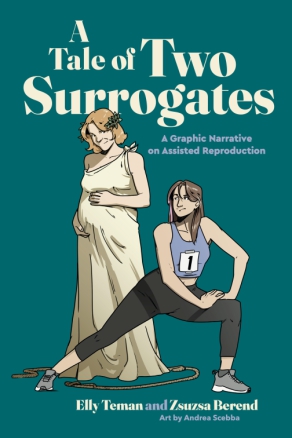

In A Tale of Two Surrogates (2025), sociologist Elly Teman and anthropologist Zsuzsa Berend bring years of ethnographic research to life through the vivid and accessible medium of comics. The graphic novel delves into the complex emotional, medical, legal, and ethical terrain of assisted reproduction, following women whose lives intertwine through their experiences as gestational surrogates.

Blending scholarly insight with compelling visual storytelling, A Tale of Two Surrogates bridges the worlds of academia and popular narrative, offering both a window into the lived realities of surrogacy and a model for how comics can communicate social science.

Comics librarian and 2022 Eisner Award judge Jameson Rohrer sat down with Teman and Berend to discuss how this groundbreaking project came to be, what inspired their turn toward the graphic narrative format, and how visual storytelling can reshape the way we teach and understand ethnography.

Rohrer: What drew you to this graphic narrative?

Teman: We were both frustrated during the Covid lockdowns and felt the need to do something creative to keep ourselves sane. I had read the graphic novel Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth about the foundational quest in mathematics, and my husband has always been a fan of non-fiction graphic novels so they were around our home. I convinced Berend that this could be a fun and interesting project to undertake together and that was before we even knew about the growing body of comics on health and illness in the Graphic Medicine world. We also both shared the observation that our students have become increasingly visually oriented, and we thought an ethnographic graphic novel could be useful for teaching this new generation of students. After we decided to do this project we found some of the anthropological graphic novels that were being published and that made the project feel more concrete. We also knew that there is a general interest in surrogacy beyond academia and thought this could be a good medium for communicating some of the take home points of our research to non-academic audience.

Rohrer: What inspired you to shift from academic research to the graphic narrative format for this project?

Berend: We didn’t really “shift”; we relied on our own and our joint publications to create a graphic novel. It was more like an expansion, a creative way of communicating the findings from our empirical research through a different kind of storytelling.

Rohrer: How did your disciplinary backgrounds in anthropology and sociology influence the storytelling in the book?

Berend: We didn’t want to do a fictional story; as social scientists, we wanted to be true to our data when we created the storyline, we chose commonly occurring events and outcomes and issues and followed the chronological trajectory of surrogacy arrangements. We searched out data for good, representative quotes and stories, we did not go for sensational outliers.

Teman: I think that because we think like an anthropologist and a sociologist, it was important for us to show how surrogacy is embedded in cultural context (Israel vs. US), religious context (Jewish vs. Christian), regulatory contexts (the lack of Federal legislation on surrogacy in the US vs. Israel’s centralized national regulation). Our disciplinary backgrounds also influenced the tone of the book in that our characters question the cultural assumptions and myths about surrogacy. We use our empirical data to show how the surrogate’s “talk back” to the often-held stereotypical views of surrogates and even to the theoretical debates about exploitation, commodification, and surrogates’ motivations.

Rohrer: How did you structure and coordinate the writing and visual narrative across alternating chapters and different settings? Were there unique challenges in ensuring narrative coherence when interweaving two geographically and culturally distinct stories?

Zsuza: We worked out the two storylines together, tweaking it many times in the process. We collected our quotes, tried to avoid repetitions, storyboarded the whole book, revised… It helped that we had already co-written several comparative articles, discussed/compared our data for years. Knowing and understanding each other’s data was essential: we understood the similarities and differences in the two countries as well as the socio-cultural and political reasons for them.

Teman: After around a year and a half, we had completed most of the storyboard and we searched through lots of graphic novels to agree on a style we liked. Then we searched through online portfolios of artists who had the style we wanted. Then we found Andrea and worked out a pattern of working with him. Teman would send Andrea the storyboard for a chapter. Andrea would sketch a page, send it by chat to Teman back and forth to tweak it. Then Teman would send it by email to Berend. Berend would okay it or make a suggestion for a change. This would happen again until the sketch was ready to be inked. Same with inking: Teman and Andrea back and forth on messenger, then Teman sends Berend by email, then changes. Same with the lettering. Each page took between four days and a week.

There were many challenges because of this: Andrea had a lot of very cool ideas and we loved a lot of them and were often surprised by the creative way he used his knowledge of art history (in drawing the Greek chorus of surrogates, for instance), of comics (in scenes such as where Jenn’s mom points at her across the panel, breaking the fourth wall), etc. But there were also some creative ideas that Andrea had that we ended up not going for because we felt that they were not exact in regard to the empirical data, and I think that was a challenge for Andrea to work with two professors who were so determined to stick to the data.

On Research and Representation

Rohrer: How did you develop the composite protagonists of Jenn and Dana from your ethnographic data?

Berend: We wanted to avoid sensational outliers, while integrating some common expectations, joys, disappointments, medical problems, etc. We worked out two storylines that were similar to many ordinary surrogacy stories in our data. Jenn’s mother and sister end up becoming less critical and more accepting without being fully on board, for example, which happens frequently. There are cases when surrogates cut ties with family members over disagreements, but again, we tried to avoid very dramatic paths. The overall higher level of acceptance of surrogacy in Israel is reflected in Dana’s story, although there are some critical views as well that we incorporated.

Teman: The composite characters were developed from the ground up. We wrote down all the themes we saw in our data. Then each of us marked a theme as “their” chapter. Then we aggregated a lot of quotes on that theme from our data, so for instance, on the topic of gift giving we both had lots of quotes and ended up having the gift theme go across two chapters (gift and then acknowledgement). The idea for the takeaways for each chapter were based on the quotes we listed under that theme, and we kept breaking up chapters as the themes got too big. We allocated quotes that show different views on each theme to the main characters’ interactions with other surrogates in their online communities. So Jenn and Dana emerged thematically from the mapping of our themes, and they became representations of our data.

Rohrer: Were there any real-life stories or moments that you struggled to adapt to the narrative?

Berend: All of the story incorporates real-life stories and moments. But there was one issue that we particularly struggled to portray: how the surrogates in my data were less attached to their eggs than the Israeli surrogates were. We tried to show this in the storyline where Jenn offers her eggs to the intended parents when she finds out they need a donor, but could not find a good contrasting emphasis to dramatize in the story how Israeli surrogates would never do that.

Teman: Something else we could not fit into the story was the different levels of loss the surrogates in Berend’s data spoke about, but we did make sure to put in Jenn’s story the one episode of loss. We also could not fit into the story the religious Jewish surrogates in my more current data, because that opens up really complex issues regarding Jewish law that would have taken a whole tangent to illustrate.

Rohrer: How does the book address the ambivalent emotions (joy, hope, heartbreak) experienced by the surrogates?

Berend: We were determined to represent ambivalence, however hard it is in this format, and comic artist Andrea’s compositions and drawings of facial expressions helped convey complex issues (e.g., ch. 8 when Jenn is grappling with embryo transfer issues). We also selected quotes that showed ambivalent emotions, hesitation, and the interpretive work surrogates do. When we represented nuance and complexity, we realized that less text is often better, since we could not do the analysis we do in monographs and articles, and reliance on the graphic medium is the way to go.

Teman: I would add that this is something we learned from Andrea. He would often tell us less text and that he could draw things instead. We would send him each page with a detailed storyboard indicating the kind of emotion we thought the character should express but he had to make that happen.

Family and Relationships

Rohrer: How are family members (spouses, children) affected by the surrogacy experience for both protagonists?

Berend: Both surrogates spend time convincing their husband and preparing their kids. Overall, the immediate families are on board, and Dana’s larger family is also supportive. As so much of our data show, families do their part at home, picking up some of the household work and dealing with the emotional issues in case there are some problems with the IPs, but generally, the families are proud of the surrogate and, unless there are some medical issues, there is no adverse effect. (My personal view is that surrogacy impacts the surrogate’s kids much less than moving to a different city and different school do!)

Teman: I’d add that based on conversations I’ve had with surrogates’ kids years later, they are proud of their mom for doing this but it does not remain a big deal, it happened and is over and “what’s next”. The husbands find themselves doing a double shift that they did not necessarily sign up for. Husbands often see themselves as very central to this journey and I think we conveyed in the characters of the surrogates’ husbands in the graphic novel how involved they can be. Mike is more involved throughout and emotionally supportive of Jenn. David is present but less involved during Dana’s pregnancy but suddenly after the birth he indicates how the surrogacy process affected him. The story also depicts two different trajectories we saw in our data about the extended family– Jenn’s mom and sister have to come to terms with Jenn’s decision to be a surrogate, versus Dana’s grandmother and sister who are very supportive but protective.

Rohrer: How do Jenn and Dana communicate and negotiate their roles with the intended parents?

Berend: Both surros make efforts to convey their desire to help the IPs and their support for the “IPs’ pregnancy” and parenthood. They try to be understanding and patient, although at times feel the need to assert their own views and stand up for their interests (medical decisions, contract negotiations, some independence, etc.) They try to convince their IPs that they are trustworthy and responsible as well as informed and helpful.

Teman: The relationships are representative of two different models that come up in our data: blurred boundaries versus distance. Of course, there are all sorts of variations and in-betweens, but these are two models we saw often enough. In Israel, where it is a small country with very emotive/intense/mediterranean familism, I (Teman) observed intense relationships between surrogates and IMs especially in which IMs would usually accompany surros to every appointment and sometimes it was too intense, like in Sarah and Dana’s case. Pages 108-109 show the tension between shared pregnancy versus suffocation. In the US, where IPs often live in different states or even countries, the surros in Berend’s data often experienced the relationship over telephone or internet. Sometimes surrogates like Jenn expected more and were disappointed by the distance, even though they were treated respectfully (see Jen on page 133 speaking to Ann about the distance). Of course, sometimes in both countries surrogates were not treated respectfully.

Rohrer: What was the most challenging aspect of balancing empathy for all parties involved?

Berend: We did try! By presenting the IPs’ perspective in some key moments we tried to draw attention to the other side. Our research was more centrally on surrogates, so the book reflects this, but having some understanding of IPs illuminates how conflicts can emerge, and how surrogates try to give the IPs the benefit of the doubt, because in some situations the parties’ interests do not coincide, even with the best intentions.

Teman: My research was also on IPs, so we drew on that as well, to show some of the reasons that Dana’s intended mother Sarah, for instance, might have been a bit too controlling. We show her long infertility journey, her fear of more disappointments, her understanding that she might cause bad luck/the evil eye, and her need to transition to motherhood through her relationship with Dana. These are all based on my research with intended mothers.

Rohrer: Jenn relies on online surrogacy forums; what role does online community play in her journey? And did you find the “chorus” of online voices analogous to support groups you’ve seen in other contexts?

Zszusa: Online support was key in Jenn’s story and social media was very important in Dana’s story. The online communities were the source of support, advice, guidance, encouragement, empathy, understanding. The Greek chorus that accompanies Jenn on her “journey” was nicer than the actual support forum I studied which had quite a bit of judgment and competition as well as much support and sane advice. However, it would have been too complicated and distracting to portray the online support group as more contentious; it would have involved a fuller portrayal of the different views and goals women have and it would have undermined the tighter structure of our book and its focus on the two surrogates. Overall, such support was essential for the surrogates in the US and Jenn’s story realistically shows some of the key variation and the types of advice women received. I was surprised, actually, during my research to see that some other support forums on other topics were much less contentious, more sympathetic and accepting, than the surro forum I researched (e.g., a PTSD support forum for veterans or cancer support groups had no cattiness or outright judgment of others!).

Legal and Medical Challenges

Rohrer: What legal or medical hurdles did each surrogate face, and how did these differ by country?

Berend: The legal and medical hurdles can be understood in the context of socio-political and regulatory contexts. Jenn has to advocate for herself more because there is much less regulation in the US. Dana asserts herself in medical decisions, highlighting her own expertise and knowledge of her own body.

Legally, Jenn must negotiate the terms of her own contract with the cooperation of her lawyer and the IPs lawyer and through the shared advice of her online surrogacy community who tell her what to watch out for. Dana on the other hand relies mostly on the state and has to go through the screening and approval process of the centralized state committee. The standard contract includes protections that she might not have advocated for herself such as babysitting and cleaning help. The story arc that addresses the legal processes in each of the surrogates’ stories is based on a comparative article we wrote called “Individual responsibility or trust in the State” which was published in 2021 in the International Journal of Comparative Sociology.

Teman: Medically, the two women represent two different ways surrogates go through surrogacy. Jenn tries her best to do the hormone protocol as well as she can and she does not question that this medical protocol is the right way to go. Dana, who lives in a country with national medical coverage, advocates for a natural cycle transfer in which she will not receive hormone support. This is possible because she can go to the clinic for daily observation of her ovulation and uterine thickness. This would not be possible in the US where health insurance might not cover so many ultrasounds and blood tests because the surrogate wants to avoid hormonal intervention. The surrogates in Israel often want a natural cycle transfer and negotiate for this type of protocol just as Dana does in the story.

Rohrer: How did these hurdles impact their sense of agency or their relationships?

Berend: Jenn compromises and caves a little more in legal/medical negotiations because of her definition that she is helping create a family for her IPs and is willing to make some sacrifices for them, and because there are fewer and less stringent regulatory constraints. Dana balances her own sense of what is safe and her own family interests with some concessions to her IM’s desire for control and safety. But she doesn’t have to worry about legal negotiations as the contract is mostly a given in Israel, so surrogates usually only make a few changes since the basics are covered.

Teman: I think that each of our main characters shows agency– Jenn in the legal advocacy of her contract, but less when it comes to the pressure on her medically to transfer more embryos. Dana shows less agency in the legal process and relies on the state, but in the medical aspect she advocates for her own embodied knowledge and resists the doctor silencing her and forcing her to do a medical protocol that she doesn’t want to do.

Social and Cultural Context

Rohrer: How are attitudes toward surrogacy different in Israel vs. California? How does the book portray these contrasts?

Berend: There are some negative views, e.g., in the US that destitute women do surrogacy for money, or that surrogates are too focused on money and neglect their own kids, and we portrayed Jenn’s mother and sister as holding such views (which we found in the US data). Strangers also often ask about money, as in Jenn’s story. In both countries there are also notions that surros compensate for an abortion they had earlier in their life, as Dana’s friend represents. In both countries there are contentions that surros bond with the baby, and Dana’s friend also expresses such a view. We didn’t want much repetition, so tried to have the two stories show a variety of views without much overlap, even if some of these notions are present in both countries.

Teman: Because of Israel’s pronatalist culture and policies, popular perceptions of surrogacy may well be more positive than in the US. We portray this especially in the response to the Jenn’s birth announcement in her church group, where she is criticized by some and praised by others (p.162). Contrastingly, we show how Dana’s birth announcement is received on FB, and as in Teman’s data (p.159), most surrogates are praised for having done what is seen almost across the board as a mitzvah/good deed, whether or not the surrogate was compensated.

Rohrer: The graphic narrative includes international vignettes—did these brief “interludes” broaden your perspective? How?

Berend: We reread several books and articles looking for representative quotes that fit with our storyline and address some of the same issues in different socio-political and regulatory contexts. We already had a sense of the scholarship that they documented, and wanted to show a broader landscape. We also wanted to highlight how our two countries, in spite of the various differences, were more similar than different in many ways. We were hoping to broaden the readers’ views.

Teman: We found it tricky how to portray these vignettes because the ethnographies we had read often stressed the way the surrogates’ lives were “discounted” (as in Rudrappa’s book Discounted Lives) and how they had to keep surrogacy as secret (as in the scholarship on surrogacy in Russia), but also that they had agency in that they were trying to better their lives. It was a challenge to portray that in one quote on one page. The artist we worked with, Andrea, came up with the idea of showing some kind of touristic monument on most of those pages and then the voice of the surrogate who you cannot really see on most of those pages. We thought it expressed the reproductive tourism aspect as well as the ethnographic project of showing the surrogate’s voices.

Ethics and Impact

Rohrer: What did the story lead you to question about the ethics of surrogacy, both in individual cases and society-wide?

Berend: We did nor directly take up ethical issues but hope that the complex empirical issues we present orient readers to some such questions, without necessarily being able to answer them. Surrogacy is a changing practice, as we see toward the end, when Jenn’s coworker tells her about new developments in the US, and also the last Interlude shows some new issues. There are no ready answers, but one can draw some conclusions from how things work out in empirical situations.

Teman: I would add that there’s an overall message in the book that Jenn felt more protected when she could have a say in her contract and that Dana felt more protected because of the regulation. Conversely, the interludes show that in countries where there is no regulation at all or where surrogates cannot read the contract let alone advocate for changes, that they may very well be harmed by the things that other ethnographers have documented in those contexts. So, we do make a commentary about surrogacy being potentially harmful to the surrogate and regulation of some degree being a way to make it less harmful.

Regarding the other ethical arguments that are commonly made about surrogacy, we show that surrogates do not necessarily view themselves as exploited or commodified or harmed and that there are indeed ethical issues that should be addressed, such as pressures on surrogates to transfer multiple embryos, such as pressures on surrogates to do the medical protocol the doctor wants even if they are a candidate for a natural cycle, and such as pressures on surrogates in places depicted in the interludes to have a cesarean as part of the deal.

Rohrer: What has been the feedback from healthcare professionals or educators regarding the use of your narrative in raising awareness or prompting discussion about assisted reproduction?

Berend: We hope to hear from professionals, educators, students, and whoever reads the book! We think of it as a discussion starter and intro to reading more; we hope people will. Our book is not a summary about how surrogacy is in these two countries, rather, it’s designed to intrigue people, help them understand some issues better, and ask more questions and read more.

Teman: We were excited that on a Facebook group for surrogates and IPs one of the intended mothers wrote that she read the book and loved it especially because she said it showed the challenges and disappointments and did not gloss over them in a romanticized way. We also asked one surrogate, one mother through egg donation, one gay dad who had two kids through surrogacy, and one intended father together with his adult daughter who had been born through surrogacy, to do close readings of the book before we finalized it and they all had really important suggestions for certain things we needed to fix.

Actually, the best feedback I got was from a 12 year old girl whose brother was born through surrogacy who told me that she learned a lot about how her brother was born but that she did not understand everything.

Rohrer: Were there moments in Jenn’s or Dana’s journeys that surprised you?

Berend: No real surprises… although sometimes the logic of the story discouraged certain turn of events as too dramatic. While there were such stories in our data, they did not really fit our narrative arc.

Teman: I think the end surprised and maybe delighted us to finally figure out how the two stories connect.

As an aside, what most surprised us was how amazing the Graphic Medicine community is and how artists can communicate such nuance through comics. We were both impressed by some of the talks at the Graphic Medicine summit we attended online this past summer, and we are both really feeling lucky to be included in this world of Graphic Medicine. Since our book is the first graphic ethnography in the PSU Press series, we hope there will be more.

This interview took place at the Comics & Care Collective: A Graphic Medicine Book Club, Monday August 11, 2025 7pm Pacific Time Zone US

© 2025 Elly Teman, Zsuzsa Berend, and Jameson Rohrer

![]()